Mental Health Promotion

Key points

- The mental health of immigrant and refugee children and youth can be promoted by examining risk and protective factors. Such factors are characterized by individuals, by their family and by environment.

- Enhancing protective factors and reducing risk help to build resiliency.

- Immigrant and refugee children and youth face barriers that affect access to care. Providing culturally competent care helps reduce these barriers.

Introduction

Mental health promotion can enhance the ability of individuals to improve their mental health. The overarching goals of mental health promotion are to increase personal resilience by building on protective factors, and to decrease risk factors through care, counselling and the reduction of inequities.1

Health care professionals can help promote the positive mental health of young newcomers to Canada by:2

- Identifying and addressing risk and protective factors and supporting increased resilience.

- Identifying and addressing barriers to positive mental health.

- Reducing inequities by providing culturally appropriate care.

Risk and protective factors

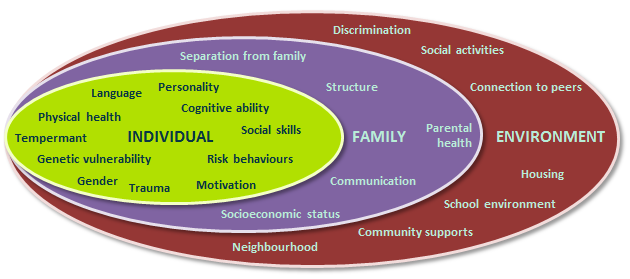

When looking at healthy youth development, much research has been done on the concept of resiliency, risk and protective factors and coping.3 For many years, health care providers have used the idea that healthy child development can be supported by increasing protective factors and reducing risk.4 For children and adolescents such risk and protective factors can be characterized individually, by the family as a whole and by environment or living conditions. Individual factors can include temperament and genetic predisposition as well as social developmental factors. Family factors include family functioning and communication. Environmental factors include relationships with people outside the family, the family’s present living conditions, and their wider social involvement and activities.

Figure 1. Protective and risk factors across systems

As Figure 1 illustrates, protective factors for a child exist across systems. A child’s individual protective and risk factors occur in the context of their family, which in turn are influenced by the environment. These factors interact constantly. When assessing and treating an immigrant or refugee child, all systems should be considered.5 Many of the factors identified in Table 1 also apply to immigrant children who are not refugees.

Table 1: Risk and protective factors for mental health in refugee children

| Protective Factors | Risk Factors | |

| Individual factors |

|

|

| Family factors |

|

|

| Environmental factors |

|

|

| Source: Adapted from Fazel M, Reed RV, Panter-Brick C, et al. Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: Risk and protective factors. Lancet 2012;379(9812):266-82. | ||

Case examples

The following case examples outline how different protective and risk factors can affect immigrant or refugee children.

A teen from China

Lily is a 14-year-old who moved to Toronto with her parents 8 months ago from China. Lily’s primary language is Cantonese, although she speaks some English. In China, Lily was involved in many activities and had a large group of friends. Since coming to Canada, her grades at school have dropped, she is not involved in activities, and she tends to socially isolate herself. She is beginning to avoid going to school and to other places where other young people may be.

Questions to consider:

- What are the primary concerns?

- Feelings of social isolation and loss of peer group

- Language difficulties may be a barrier to school achievement and contribute to isolation

- What are the next steps?

- Complete a HEADSS assessment to determine social stressors and assess for psychiatric symptoms, including suicide risk. Book a follow-up appointment to assess whether mood symptoms have resolved once additional supports are in place.

- What services should Lily be connected with?

- Newcomer youth or community groups

- ESL courses

- A school guidance counsellor, optimally with her parents involved, to discuss specific accommodations and course load. Provide letters of support when needed.

Learning points:

The aim is to to enhance Lily’s protective factors and reduce her risk factors at each level: individual, family and environmental.

Individual

- Help connect Lily with local ESL services.

- Advocate for specific supports at school.

- Connect her with culturally appropriate community agencies or groups.

- Encourage involvement in activities she enjoys, to promote self-confidence.

Family

- Suggest to parents that they ask Lily to choose family activities.

- Take a family psychiatric history.

- Connect parents with community supports they may need or groups they might enjoy.

Environmental

- Connect Lily with community organizations that promote positive youth development and engagement.

- Assess her exposure to discrimination and advocate directly with the school if bullying or other stressors are occurring. It may also be appropriate to provide letters of support for psychoeducational testing or an Individual Education Plan.

A teenage refugee from Uganda

Bessa is a 15-year-old refugee from Northern Uganda. She has lived in Canada for 14 months. Before immigrating, she was kidnapped from the family home by a group of men and held for 2 days. She was physically and sexually assaulted during that time. Since being in Canada, Bessa has connected with a youth group and a small group of friends. However, she often experiences interpersonal difficulties within this group. Bessa has a history of sleep disturbances, often finding it difficult to fall asleep and waking from recurrent nightmares. She speaks of seeing male figures at her bedroom window at night and following her to school. Police have been contacted several times, but no evidence of these men has been found. She has also said that she hears people laughing at her, which her friends and family have not observed.

Questions to consider:

- What are the primary concerns?

- Experience of trauma and possible psychiatric symptoms.

- Ongoing social stressors and feelings of isolation.

- Possible depressive, anxiety, psychotic or post-trauma symptoms.

- What are the next steps?

- Exercise empathy and cultural sensitivity when conducting this assessment. Consider having a female staff member present. Ensure sensitivity around discussion of trauma and present symptoms, and make sure the assessment is not retraumatizing Bessa.

- Complete a HEADSS assessment to determine social stressors and identify psychiatric symptoms. Part of the HEADSS assessment includes a suicide risk assessment. Book a follow-up appointment to assess whether mood symptoms have resolved once additional supports are in place.

- Elicit perspectives on Bessa’s history and presentation from her parents or other representatives of her cultural community, if possible.

- What services should she be connected with?

- Refer to mental health services or trauma-based counselling services.

- Refer to community group, youth group.

- Connect with ESL services, supportive services for new Canadians, and specific school-based supports.

Learning points

The aim is to to enhance Bessa’s protective factors and reduce her risk factors at each level: individual, family and environmental. It is clear she has been exposed to numerous risk factors.

Individual

- Bessa may be experiencing a mental health condition. She has a number of risk factors in this area. Referring for assessment and treatment is important.

- Encourage involvement in positive social activities to promote self-confidence.

- Help to connect her with a group that focuses on building social skills. A listing of community organizations serving immigrant and refugee youth is available in this resource.

- Educate around sleep hygiene.

Family

- Elicit parents’ understanding of the symptoms and how these are conceptualized in their family and culture of origin.

- Provide resources and psychoeducation for Bessa’s family to ensure they know how to best support her.

- Connect family with community supports they may need to ensure Bessa has a safe and stable living environment.

Environmental

- Help to connect Bessa with youth-based trauma support that is culturally appropriate.

- Assess the safety of Bessa’s environment. Provide letters of support for Immigration Canada, housing agencies etc. More information on case advocacy is available in this resource.

Promote resilience

Resilience is a person’s ability to cope with major stress or risk factors.6 Being resilient means being able to recover from adversity by adapting to change. Promoting resilience in young newcomers to Canada is a key component in promoting their mental health.2

By identifying and addressing risk factors and promoting protective factors, health professionals can help foster resilience in newcomer children, youth and families and assist in the acculturation process. Promoting resilience means focusing on an individual’s strengths and helping to nurture mental health and well-being by identifying and building on the positive connections in a young person’s life: individual, family-related and environmental. Specifically supporting such connection helps the young person to build on their own protective factors and facilitates resilience.

Factors that promote resilience in young newcomers to Canada are summarized in the Adaptation and Acculturation section of this resource.

Identify barriers to care and facilitate access

Barriers to care

Accessing mental health services can be a major challenge for immigrant and refugee families, who are much less likely to use them when needed than families born in Canada or the U.S.8,9 Barriers to care can include lack of awareness of services, financial barriers and language.8 Specific strategies that health professionals can use to lower such barriers are covered in Barriers and Facilitators to Health Care for Newcomers.

Stigma and differing cultural beliefs and practices around mental health can be additional barriers for newcomer families who require mental health services,8 and health professionals should be particularly alert to the influence of stigma, which can impede a family’s willingness to seek help.8,10

Although stigma about mental illness exists across cultures, it may be more strongly felt in some cultural communities.10 The reasons for this may be attributed to a number of factors that can vary between cultures:

- Shame: The family fears that the diagnosis of a mental health condition will bring shame to the person, limit achievement (e.g., access to higher education, finding employment or having a family). Feelings of shame can shared by the family or extended family or even to a cultural community on the family’s behalf.8 Families often worry that they or their child will be rejected by their community.

- Differing perceptions about mental health: It is important to remember that differing cultures have differing approaches and treatment options to mental health. It is important for the practitioner to understand how and why a newcomer family’s perspective on a mental health issue may diverge from a proposed treatment plan. The family may hold very different views regarding possible causes of mental illness (e.g., a curse or negative spirit) and treatment options. They may have been less exposed to mental health-related media or literature, and may also be culturally conditioned to avoid dealing with psychological issues directly.11 Health care professionals need to provide clear, supportive information about diagnosis and available treatment options, and help to develop a collaborative treatment plan agreeable to both the patient and, optimally, family members. More information about negotiating treatment plans with newcomer families is available in this resource.

Health care providers can help to mitigate stigma by providing clear information about what causes mental health problems and practical guidance on treatment. Emphasizing that confidentiality is a patient right in Canada can build trust, especially in adolescent patients.10,11 Suggestions for how to frame questions to help reduce stigma are given in Table 2. Wider anti-stigma campaigns tailored to specific minority groups are also needed.

Table 2. How to ask questions about mental health

| Suggestion | Examples |

| Focus on questions around behavioural changes |

|

| Use a strengths-based interview style to help the patient feel empowered |

|

| Validate distress around possible somatic symptoms. |

|

| Normalize the mental health experiences of children and youth |

|

| Use analogies related to physical conditions |

|

| Ensure the clinical setting is welcoming to adolescents |

|

Provide culturally appropriate care

Initially, newcomers to Canada may not believe in the biomedical model of mental health care. They may view mental health services as inappropriate or ineffective.1 Health care providers can help by ‘setting the tone’: providing timely, culturally responsive care at the first visit. For more information, see Cultural Competence for Child and Youth Health Professionals.

In the context of mental health promotion, providing culturally responsive care is of particular importance when taking a history, for example:

- Explore and assess the patient’s immigration experience. Look for immigration-related stressors or trauma, which may predispose to post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health issues.12,13

- Ask about traditional, complementary and alternative treatment modalities that a patient may be using. These may include acupuncture, spiritual healing, herbal supplements and traditional medicine and are often not volunteered by patients or families. They cannot assumed to be absent, or harmless, unless specifically discussed.

When treating young people, health professionals should consider the following:

- Be aware that any given culture can include varied ethnic, language, and social backgrounds. These may all affect the child’s or adolescent’s health.

- Avoid cultural stereotyping—not everyone from the same background will have the same attributes, beliefs, and practices.

- Be aware that children’s and adolescents’ experiences, such as migration, exposure to war and trauma, discrimination, etc., can affect their health and mental health.

- Ask about culture and cultural identity and what it means for the patient.

More information about carrying out a culturally appropriate consultation, including taking a history, is described in the Cultural Competence section.

Presentation of mental health problems

The presentation of mental health problems in young immigrants or refugees may differ from that of their Canadian-born peers. Newcomers may be reluctant or have difficulty verbalizing their symptoms due to factors such as the stigma associated with mental health conditions or language barriers. Patients may present with chronic nonspecific physical complaints. Clinicians should be alert to vague or subtle symptoms or shifts in behaviour when such symptoms are discussed.

Examples of nonspecific mental health symptoms and behavioural changes that children and youth who have been exposed to violence may present with are listed in the Table 3.

| Table 3. Examples of non-specific symptoms and behavioural changes in children and youth exposed to violence | ||

| Child ≤5 year of age | Child 6 to 12 years of age | Youth 13 to 18 years old |

|

|

|

|

Source: Adapted from Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2010. Trauma informed care for children exposed to violence: Tips for agencies working with immigrant families. |

||

For more information on somatic complaints, see the section on Depression on this website.

Recommended resources

- American Psychological Association, 2009. Working with refugee children and families: Update for mental health professionals.

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 2012. Best practice guidelines for mental health promotion programs: Refugees.

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 2014. Best practice guidelines for mental health promotion programs: Children and youth.

- Fong R (Ed.). Culturally Competent Practice with Immigrant and Refugee Children and Families. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2003.

- Kelty Mental Health Resource Centre. Families, together: Supporting the mental well-being of culturally diverse families, children and youth [video and discussion guide]. Several resources are available in French and other languages.

- McCreary Centre Society, 2011. Making the right connections: Promoting positive mental health among BC youth.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Improving mental health services for immigrant, refugee, ethno-cultural and racialized groups: Issues and options for service improvement. 2009.

- McGill University. Multicultural Mental Health Resource Centre. Provides information and handbooks on culturally competent assessment and care.

- Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health, 2015. Responding to the mental health needs of children, youth and families new to Canada.

- Ottawa Public Health, 2019. Mental Health = Health (Video).

References

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Best practice guidelines for mental health promotion programs: Refugees. 2012: https://knowledgex.camh.net/policy_health/mhpromotion/Documents/BPGRefugees.pdf

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Best practice guidelines for mental health promotion programs: Children and youth. 2013: https://knowledgex.camh.net/policy_health/mhpromotion/mhp_childyouth/Pages/default.aspx#guidelines

- Garmezy N. Stress-resistant children: The search for protective factors. Recent Research in Developmental Psychopathology 1985;4:213-233.

- Resnick M. Protective factors, resiliency, and healthy youth development. Adolescent Medicine: State of the Art Reviews 2000; 11(1): 157-64.

- Fazel M, Reed RV, Panter-Brick C, et al. Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: Risk and protective factors. Lancet 2012;379(9812):266-82.

- Kilbride KM, Anisef P. To build on hope: Overcoming the challenges facing newcomer youth at risk in Ontario. Toronto, Ont.: Joint Centre of Excellence for Research on Immigration and Settlement, 2001.

- Gunnestad A. Resilience in a cross-cultural perspective: How resilience is generated in different cultures. J Intercultural Communication 2006;11.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Improving mental health services for immigrant, refugee, ethno-cultural and racialized groups: Issues and options for service improvement. 2009: www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/document/457/improving-mental-health-services-immigrant-refugee-ethno-cultural-and-racialized-groups

- Snowden LR, Yamada AM. Cultural differences in access to care. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005;1:143-66.

- Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, et al. Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and U.S.-born Black and Latina women from seeking mental health care? Psychiatr Serv 2007;58(12):1547-54.

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodríguez M, Paradise M, et al. Cultural and contextual influences in mental health help seeking: A focus on ethnic minority youth. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002;70(1):44-55.

- Beiser M, Armstrong R, Ogilvie L, et al. The New Canadian Children and Youth Study: Research to fill a gap in Canada’s children’s agenda. Canadian Issues/Thèmes Canadiens 2005:21-4.

- Salehi R. Intersection of health, immigration, and youth: A systematic literature review. J Immigr Minor Health 2010;12(5):788-97.

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Trauma informed care for children exposed to violence: Tips for agencies working with immigrant families. 2010: http://www.justice.gov/defendingchildhood/tips-immigrant-families.pdf

Reviewer(s)

- Katie Stadelman, MSW, RSW

Last updated: March, 2023