Using Interpreters in Health Care Settings

Key points

- Accurate assessment of any newcomer child or youth requires complete, optimal communication without misunderstandings on either side. Often this can only be achieved in collaboration with an interpreter.

- Engage a trained cultural interpreter for your newcomer patients whenever possible.

- There are certain risks involved with using a patient’s family members or friends as interpreters. Avoid the use of children and youth as interpreters.1-4

Dr. Meb Rashid of Toronto’s Crossroads Clinic talks about using interpreters in this CBC radio interview. “One clinic, hundreds of languages: Here’s how it works”, December 2, 2016

Interpreters are important

Many newcomers to Canada do not have English or French language skills sufficient to understand what information a health professional is looking for or to provide a thorough history. Also, communication with immigrant and refugee families can be seriously impaired if a health care provider is unaware of or insensitive to the role of culture in formal interactions. Miscommunication can increase the risk of medical errors, inappropriate treatments and emergency room visits.1,3 Cultural interpreters can play a crucial role by facilitating verbal and nonverbal communication and ‘mediating’ concepts and cultural practices as needed.

Interpreter or translator? Each profession involves different skills.

An interpreter works with spoken language, often translating and mediating between two languages in both directions, on the spot, without the aid of a dictionary. A translator deals with written language and excels at clear, accurate expression in written form, usually in one direction and typically, from a source language into their own native tongue.

In both professions, understanding meaning and nuance of one language and being able to express them in another language are crucial skills. Often, this process requires understanding the culture behind each language.

Roles of the cultural interpreter

Cultural interpreters can facilitate clinician–patient interaction in a number of ways. In any office visit between a physician or other care provider and newcomer family members, a skilled interpreter can:

- Help ensure that everyone understands both words and meaning ‘in the moment’, as they are being used.

- Provide a clear and precise interpretation of the care provider’s questions and the family’s answers, while being open to additional questions about what patient (or practitioner) responses might mean.

- Assist the communication process without leading it. An interpreter should not be ‘in charge’ of an interview, which may be likelier to happen if the interpreter was a health professional in their former country.

- Understand the family’s situation and specific issues, and be able to supply some cultural background for the clinician (e.g., why a particular family is responding a certain way during an interaction).

- Steer the clinician away from actions or words that might be culturally inappropriate and help to prevent or clarify misunderstandings on either side.

- Explain the role of the clinician to the family and encourage them to ask questions.

- Respect the confidentiality and integrity of everyone involved. An experienced interpreter will often start an office visit with introductions, explain their own role, and provide assurance that everything to be discussed will be kept private and confidential.

An interpreter can also help establish links within the family’s local cultural community, if such a network is available and the family consents to this level of involvement.

Skills and qualities to look for

A highly skilled interpreter possesses a wide range of skills and abilities, including:

- Professional training and certification

- Some grounding in health issues and understanding of medical terms.

- Some knowledge of close language ‘families’ and related dialects.

- An ability to interpret nonverbal expression (e.g., speech patterns, gestures and facial expressions).

- Some awareness of intercultural issues (e.g., different value systems, the role of individual family members, common taboos, and attitudes toward authority).

- Self-confidence, integrity, attention to detail and flexibility.

- A sound grasp of Canadian health care settings and processes.

Able interpreters may have been health professionals or teachers in their former country but have not had their qualifications recognized or are not yet able to practice their profession in Canada.

Newcomer families may be especially sensitive about sharing medical information. Clinicians must make sure that an interpreter is acceptable to the patient’s family. If an interpreter comes from a rival background – tribal, ethnic, clan or other – the family may not be able to trust an individual from that group. In such cases, you may need to stop the interview, excuse the interpreter, and start afresh.

Determine whether an interpreter’s services are needed at time of first appointment. This usually allows enough time to find and book the interpreter.

Finding an interpreter

Enlisting the help of a professionally trained cultural interpreter who works with a hospital, local health department or community cultural organization is the best option.

- Often, these professionals are designated specifically for work with one or more cultural, language or ethnic groups. They are available by appointment and remunerated on a per hour basis.

- Some hospitals (especially in major Canadian cities) access a pool of volunteers or have salaried staff who can help clinicians communicate with immigrant or refugee families. However, hospital staff with other clinical or work responsibilities may not always have the time or flexibility to help with a thorough interview or history-taking. Hospital volunteers may not be formally trained as interpreters.

- In Quebec, an interpreter can be requested through the patient’s centre de santé et des services sociaux (CSSS). Requests must be made in advance and approved by the CSSS. Costs are covered by the CSSS.

- Another option is to use the AT&T Language Line, which may also be considered in emergency situations.

Using untrained interpreters

When professional interpretation is not possible, arranging for the family to bring a relative or friend to the appointment to act as an interpreter is the next best option. Clarify that their choice should be someone whom they can trust with the family’s confidential medical information. Also, bear in mind the potentially protective bias of a family interpreter: they might withhold or change information to avoid conflicts. A community representative is often preferable to a family member. Using an untrained interpreter is riskier and health professionals need to take extra care to ensure that their communications are being well understood.4,5

Best practice is to avoid the use of children and adolescents as interpreters. Having to act as an intermediary between one's parents and a health professional is a heavy and unfair burden for a child. Use professional interpreters on-site, by telephone or via online phone or videoconferencing.

There are many reasons to discourage using children and youth as interpreters, including the following:

- The reliability of information they provide may be highly questionable. Children may not be aware of all relevant information, may not be confident or fluent enough in both languages to translate accurately and may alter the meaning of communications to protect family members.

- Communicating sensitive health information can be stressful for children.

- Interpreting for parents can disrupt the parent and child roles within the family, affecting dynamics adversely.

- If there is some kind of negotiation or debate involved, a child may be forced to play the role of 'broker', with loyalties divided between a health professional and the family.

Unfortunately, in some areas professional interpreters may not be available, or the cost may be prohibitive for either the patient or the health care provider. There may be cases where older children or other family members end up serving as interpreters, due to local lack of accessibility, practical issues (emergencies, trust issues, etc.) or funding limitations. When this happens, the health professional should be acutely aware of the potential pitfalls. The American Academy of Paediatrics opposes the use of children and adolescents as medical interpreters for their parents and family members.6

Public funding is needed to improve access to interpreter services.

In case of emergency…

If an interpreter cannot be found, health care providers can use the AT&T Language Line in the United States or in Canada by phoning 1-800-752-6096. A language identification card is available from AT&T to help identify the language spoken by a patient. For a fee, charged to the health care provider, this service will locate an interpreter who speaks the patient’s language.

Using an interpreter appropriately

Health care providers can take a number of steps to make involving an interpreter a positive experience.

When booking the appointment

- Determine whether an interpreter is needed at time of appointment. This allows enough time to find and book the most competent interpreter available.

- Ask the child or youth if they would prefer a male or female interpreter (if there is a choice).

- Be sure to allot extra time: for a quick consult with the interpreter beforehand, for the medical visit itself – with interpretation added – and a quick ‘debriefing’ afterward. These interviews easily take twice as long as more typical patient visits.

- If you and the newcomer family have found a trusted interpreter, try to use the same person for all of their visits.

Before the office visit

- Be respectful of the interpreter’s time: they may have several other appointments scheduled that day. Avoid delays in your own appointment schedule.

- Speak with the interpreter beforehand to discuss the goals of the visit and how best to achieve them. Emphasize that families must make decisions for themselves about medical matters.

During the visit

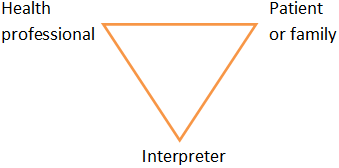

| Figure 1: Triangular Seating Arrangement |

|

- Use a triangular seating arrangement, so that everyone can see non-verbal cues, as illustrated in Figure 1.

- Introduce the interpreter and the family. Ask the interpreter to describe their own role, particularly if the family is meeting them for the first time.

- Before starting, be sure to ask the family if they feel comfortable working with this person.

- Ask the parents how much of the discussion they want interpreted. Some parents understand but have difficulty expressing themselves in English or French. They can choose to have only their answers interpreted. If they hesitate, explain that the interpreter will interpret everything.

- Explain your own role as clinician and the purpose of the visit.

- Maintain responsibility for the visit. The interpreter’s role is to convey information and discussion accurately, not to come up with medical or other explanations.

- Encourage the interpreter to intervene if a misunderstanding occurs or seems likely.

- Many newcomer families understand some English or French. Clinicians should not carry on a separate discussion with the interpreter in a family’s presence without first explaining why. Similarly, clinicians should ask the interpreter to explain the nature and content of any extended discussion with the family.

- Be respectful of the family’s culture. It may be important to direct questions to an authority figure (e.g., a father or grandparent) rather than to the patient, even though this person may not have all the information you need. Paediatricians commonly address questions to young patients but with newcomer families, respecting family authority has real value.

- When the clinician can direct questions to an adolescent patient in English or French and understand responses, be sure to ask a less fluent parent how much of what is asked or answered should be interpreted for their benefit.

- Look at family members when speaking to them and while the interpreter speaks. Speak directly, using “I” and “you” whenever possible.

- Speak slowly and clearly. Use short sentences, pause frequently to allow the interpreter to translate, and give only small amounts of information at a time.

- Avoid idioms, jargon, slang, abbreviations, acronyms and jokes, which may cause confusion.

- Repeat important instructions and explanations to reinforce health messages. If miscommunication is suspected, reiterate with different wording. Ask the patient, parent or caregiver to repeat the information back to you.

- Give enough time for the family to ask questions.

After the visit

- Have a quick debriefing session to find out if the interpreter observed anything else that a health care provider should know about.

- Whenever such resources are available, provide the newcomer family with printed material in their own language. Also try to provide written information or fact sheets on family health issues in English or French for them to review at home. Information for families on common medical topics is available in multiple languages from the Hospital for Sick Children at www.aboutkidshealth.ca.

- As required, ask the interpreter to write down instructions for the family.

- Ask if the interpreter can assist the family with scheduling follow-up appointments with the office receptionist, if needed.

- If possible, arrange for the interpreter to accompany the family for lab tests or to the pharmacy.

- Use the same trusted interpreter for all office visits with this child and family, if possible.

Selected resources

- American Medical Association. Office guide to communicating with limited English proficient patients (2nd edn., 2007). This resource describes how to identify English proficiency and interpreter level.

- Canadian Paediatric Society. Caring for Kids New to Canada Task Force (principal author: C. Hui). Access to appropriate interpretation is essential for the health of children. June 2023.

- Carter-Pokras O, O’Neill MJ, Cheanvechai V, et al. Providing linguistically appropriate services to persons with limited English proficiency: A needs and resources investigation. Am J Manag Care 2004;10(Sped No):SP29-36.

- Crossman KL, Wiener E, Roosevelt G, et al. Interpreters: Telephonic, in-person interpretation and bilingual providers. Pediatrics 2010;125(3):e631-8. This article illustrates concordance of diagnoses with different types of interpreters.

- Divi C, Koss RG, Schmaltz SP, et al. Language proficiency and adverse events in U.S. hospitals: A pilot study. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19(2):60-7.

- Flores G. Language barriers to health care in the United States. N Engl J Med 2006;355(3):229-31. This article describes one scenario where using a child as an interpreter was harmful.

- Karliner LS, Pérez-Stable EJ, Gildengorin G. The language divide. The importance of training in the use of interpreters for outpatient practice. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19(2):175-83.

- Keers-Sanchez A. Mandatory provision of foreign language interpreters in health care services. J Leg Med 2003;24(4):557-78.

- Schenker Y, Lo B, Ettinger KM, et al. Navigating language barriers under difficult circumstances. Ann Intern Med 2008;149(4):264-9. Inpatient focused with descriptions of different types of interpreters and how to select them.

- SickKids Hospital (Toronto, Ont.) Centre for Innovation and Excellence in Child and Family-Centered Care. The Clinical Cultural Competence E-Learning Modules Series has several helpful modules on health literacy, culture and health, working with interpreters and other migration-related topics.

References

- Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Dave A, et al. Trained medical interpreters in the emergency department: Effects on services, subsequent charges, and follow-up. J Immigr Health 2002;4(4):171-6.

- Bischoff A, Bovier PA, Isah, Rrustemi I, et al. Language barriers between nurses and asylum seekers: Their impact on symptom reporting and referral. Soc Sci Med 2003;57(3):503-12.

- Ku L, Flores G. Pay now or pay later: Providing interpreter services in health care. Health Aff (Millwoood) 2005;24(2):435-44.

- Keers-Sanchez A. Mandatory provision of foreign language interpreters in health care services. J Leg Med 2003;24(4):557-78.

- Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, et al. Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatrics 2003;111(1):6-14.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Paediatric Workforce. Ensuring culturally effective pediatric care: Implications for education and health policy Pediatrics 2004;114(6):1677-85.

Other works consulted

- Brotanek JM, Seeley CE, Flores G. et. al. The importance of cultural competency in general pediatrics. Curr Opin Pediatr 2008;20(6):711-8.

- Burnett A, Fassil Y. Meeting the health needs of refugee and asylum seekers in the U.K.: An information and resource pack for health workers. London, U. K.: Directorate of Health and Social Care, National Health Service. Covers types of refugees, experience before arrival, cultural and health information, with a useful list for working with interpreters.

- Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: A systematic review. Med Care Res Rev 2005;62(3):255-99.

Reviewer(s)

- Robert Hilliard, MD

Last updated: July, 2023