Obesity in Immigrant Children and Youth

Key points

- In general, particularly among families of lower socio-economic status, immigration may increase risk of obesity; the longer the stay, the greater the risk.

- Social, economic and cultural factors, including dietary acculturation, can influence overweight and obesity risk in young newcomers to Canada.

- Some ethnic populations are at higher risk of the medical consequences of obesity than others at the same or lower body mass index (BMI).

- The WHO age- and sex-appropriate growth charts are the best tools for surveying the velocity of growth before overweight and obesity in children, including young newcomers to Canada.

- As part of routine care, clinicians should counsel patients on how to prevent obesity by maintaining a healthy diet, regular physical activity, less screen time and good sleep habits.

- More research is needed to support evidence based recommendations for preventing, intervening and treating obesity, specifically in immigrant and refugee children.

Introduction

Childhood obesity represents a rising unsolved public health crisis worldwide. In Canada, the prevalence of obesity among children has increased significantly over the past decades.1 Nowadays, about one out of three Canadian children are overweight or obese, compared to one in four children in 1978-1979.2 As defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), school-aged children and adolescents from 5 to 19 years old are overweight if weight is one standard deviation above the body mass index (BMI) for age and sex (68th percentile), and obese if weight is two standard deviations above BMI for age and sex (95th percentile).3 The WHO Child Growth Standards also presents measures for overweight and obesity for infants and young children from 0 to 5 years. Here in Canada, the Endocrine Society recommends diagnosing a child or adolescent >2 years of age as overweight if the BMI is ≥85th percentile but <95th percentile for age and sex, as obese if the BMI is ≥95th percentile, and as extremely obese if the BMI is ≥120% of the 95th percentile.

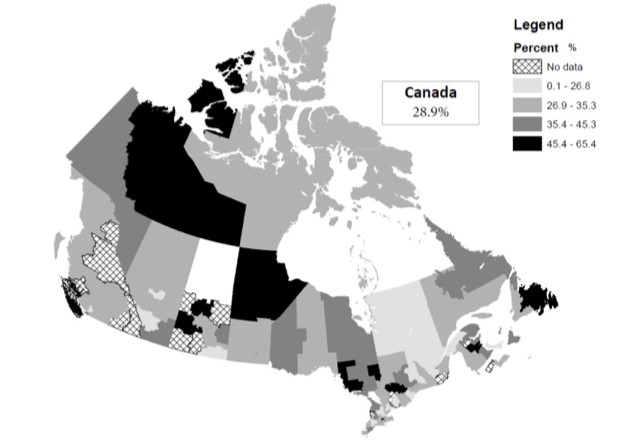

The Canadian national average of childhood and youth excess weight is 28.9%, while the prevalence of obesity is 13.1% (2013-2014 last Canadian Community Health Survey).4 Rates by provinces vary significantly as demonstrated below (Figure 1). National trends are quite similar to international rates, but at a lesser extent: the prevalence of childhood obesity in the United States is 16.9% (5) and 20% in the United Kingdom.6

|

Figure 1. Prevalence of overweight and obesity by local Canadian health region (ages 12 to 17 years) |

|

|

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey (2013-2014) |

Risk factors of obesity

Several risk factors have an impact on the development of childhood obesity. These include: high maternal BMI, excess maternal gestational weight gain, gestational diabetes, in utero tobacco exposure, high birth weight and rapid infant weight gain, no or poor breastfeeding, very early introduction of solid foods, feeding patterns, and diet, poor infant-maternal relationship, shortened infant sleep, low socioeconomic status.7-14

New findings suggest that there exists an association between antibiotic use in the early years of life and obesity risk. The effects of these therapies on gut microbiota might influence weight gain. The clinical importance and how we can change the practice of prescribing antibiotics remain however uncertain for now.15

Risk factors of obesity specific to immigrant children and youth

A number of risk factors appear to predispose young newcomers to Canada to overweight and obesity. These include:

- Immigration itself16

- Length of residence in the host country17

- Extent of acculturation to or adoption of Western lifestyles18, 19

- Genetic predisposition20, 21

- Ethnicity22

- Cultural norms23

- Socioeconomic status24

- Food insecurity25, 26

Factors such as ethnicity and socioeconomic status also influence how overweight and obesity risks increase over time.27

Acculturation and time since immigration

Overall, first-generation immigrant children appear to have lower risk of obesity than children born in the host country.28 However, the risk of obesity appears to increase with acculturation18, 19, 20 and the length of time since immigration.17 An early focus on obesity detection and prevention by health care providers can be important. Biculturalism (being engaged in both the heritage culture and in the new society) seems to protect against obesity, compared with complete acculturation in the new culture.30

Genetic predisposition

The heritability of obesity varies considerably among individuals (variance may be as much as 20% to 30%), which in turn influences the hypothalamus and its signalling molecules that play a central role in coordinating energy balance and homeostasis. Most of these factors are thought to cause obesity only when environmental conditions support them. Epigenetics may contribute to obesity, when combined with an obesogenic environment.31

Ethnicity

Certain populations, including Asian, East Indian, African-American, Native American and Mexican peoples, are at higher risk of obesity.32-35 Even at the same or lower body mass index (BMI), some people are at higher risk for medical complications when obese.36

Cultural norms

Cultural norms in a child’s country of origin can influence risk of obesity after immigration.23 For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and the Caribbean, larger body size has often been considered a mark of social status, health and success while thinness has often been associated with poverty and ill-health.37 Consuming fried food and soft drinks is sometimes considered a mark of affluence while a diet of vegetables and fruit is seen as less tasty. Some aspects of the American diet (high-fat, carbohydrate-rich), are being disseminated worldwide, which explains, in part, the obesity pandemic experienced even in developing countries.38

Socio-economic status

In developed countries, overweight and obesity are clearly associated with lower socio-economic status (SES).39 A number of reasons have been proposed:24,26

- Lack of funds, lack of transportation, and irregular parental work schedules, may limit a child’s ability to attend extracurricular activities, a family’s ability to participate in community activities or to access and prepare nutritious food.

- Children living in low-income communities are more likely to have limited access to healthy food, safe outdoor play spaces or recreational facilities. They may spend more time indoors being sedentary, watching TV or playing video games.

- Foods that are high in calories and low in nutritional value (including fast foods) are often less expensive than healthier choices. Newly arrived families often live in food desert geographic locations where there is very poor access to reasonably priced healthy food options.

Immigrant families are more likely to experience poverty than native-born Canadians at the beginning of the integration process.40 Overweight and obesity risk over time increases for newcomer children with low SES who immigrate from low-income countries.41 This relationship appears to relate to a family’s having experienced food insecurity in the past25, 28 and their degree of acculturation to new norms at a low SES level.41 Refugee children are especially vulnerable because they are more likely to be living in poverty.

Food insecurity

The degree of deprivation experienced by parents in their country of origin,41 particularly food insecurity, is a risk factor for obesity in their children.25,26 The experience of food insecurity may contribute, along with previous cultural norms, to belief that that heavy body weight is correlated with good health.

Screening and assessment of obesity

Young newcomers to Canada should be screened in the same way as Canadian-born children: by using BMI percentiles for children 2 years of age and older, and weight-for-length in younger children.40,42

The WHO published standard growth indicators in 2010, with growth curves based on children from 6 countries (the U.S., Norway, Brazil, India, Ghana and Oman) to optimally reflect the world population. Asian and southwestern Pacific populations were not represented, however. Because a large percentage of immigrants to Canada come from Asia, practitioners may wish to look at the regularity of the growth curve instead to identify at risk trends. Practitioners may wish to consult the Canadian Pediatric Endocrine Group (CPEG) complimentary growth curves for a more harmonized view of growth percentiles from 2 to 19 years of age.43

Despite the fact that BMI is a reliable measure and is easy to use in the primary care setting, it may not appropriately reflect body fat, particularly for some ethnicities. Ethnic-specific cut-off points for BMI and waist circumference are available for adults but not for children.44, 45 When interpreting BMI, bear in mind that certain ethnic populations tend to develop medical complications at lower BMI than Caucasians.34

The cut-off values and clinical usefulness of waist circumference in children are not well established. Therefore, this measurement is not recommended routinely at the present time in the primary care setting.

Screening for diabetes, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia

T

There are no evidence-based recommendations in the literature for metabolic screening specifically for immigrant and refugee children. However, current Canadian guidelines45 and U.S. guidelines46,47 are available and can serve as a useful reference for screening newcomer children.

Lipid screening: An overweight or obese child should be screened at 10 years of age and older.46 If the child has additional risk factors, such as familial cardiovascular disease or dyslipidemia, screening should be done earlier and repeated periodically.

Hypertension: All children should have their blood pressure measured yearly, starting at 3 years of age. Hypertension cut-offs for diagnosis are available. If this condition is confirmed, it requires appropriate investigation and management.

Type 2 diabetes: The 2018 Canadian Diabetes Association recommends screening every 2 years using a combination of an A1C and a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) test for children presenting and adolescents with any of the following:48

- ≥3 risk factors in nonpubertal children beginning at 8 years of age or ≥2 risk factors in pubertal children. Risk factors include:

- Obesity (BMI ≥95th percentile for age and gender)

- Member of higher-risk ethnic group (e.g., African, Asian, Hispanic, Indigenous or South Asian descent)

- First-degree relative with type 2 diabetes and/or exposure to hyperglycemia in utero

- Signs or symptoms of insulin resistance (including acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [ALT >3X upper limit of normal or fatty liver on ultrasound])

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome

- Impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance

- Use of atypical antipsychotic medications

Details on these tests can also be found in the Canadian guidelines on management and prevention of obesity.49 There are no specific screens for immigrant and refugee children.

Screening for mental health concerns

Being overweight or obese can impact a child’s mental health and well being, and can affect family life. Low self-esteem, bullying, insomnia, behaviour problems, and depression are only a few common, often recurrent, examples of frequent consequences of obesity. Immigrants often face barriers to access outpatient mental health care, partly because of the heightened stigma attached to mental health disorders in the immigrant population.49 Health care providers therefore need to be alert to such effects, ask their young patients about them, and put them and the family in contact with supportive services as needed. More information on promoting mental health in immigrant and refugee children and youth is available in this resource.

Preventing obesity

Detection and prevention are the only ways to succeed in obesity treatment. Specific preventive measures for obesity in young immigrants have not been well identified. Recommendations are the same as for Canadian-born children, with a focus on three different interventions to adopt healthy living habits: improving diet, increasing physical activity and promoting sleep. These are also the core elements of the treatment of obesity (refer to Treating Obesity).

Prevention measures must be implemented early on in life. Obesity in infancy is an important risk factor for overweight and obesity in adolescence and later on in adulthood. A retrospective analysis showed that the most rapid weight gain occurs between 2 and 6 years of age and that 90% of children obese at age 3 are overweight or obese in adolescence.50 The impact of obesity on life expectancy (less than 10 years) also urges the promotion of strong prevention strategies.51

Upstream interventions such as early childcare and education are key to obesity prevention. One should be aware of and address caregivers’ cultural beliefs and practices pertaining to child feeding. In a setting where there are multiple caregivers, parents should work on providing a uniform message regarding feeding and healthy living habits. This child-centered approach must take roots in a bigger and more upstream population approach where a public, consistent and clear message based on evidence-based strategies is shared with caregivers at all levels (parents, daycare educators, teachers, etc.).13

Some examples of population level government-implemented interventions include banning the sale of energy drinks to children and youth, limiting junk food advertising, enforcing calorie-labelled menus, taxing sugary products, promoting primary school physical activity.52 Parents can also be great examples to their children and instil in them healthy lifestyle habits.53

Dietary improvements

Efforts to improve both the quality and quantity of a newcomer family’s food intake can be based on Canada’s Food Guide, which is available in multiple languages and includes many ‘ethnic’ options. For young newcomers, consider suggesting dietary adaptations that remain consistent with traditional eating customs. The expertise of dieticians and translators in some cases, may help.

Specific recommendations include:54,55

- Exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months of age and continued breastfeeding with complementary foods for 2 years and beyond

- Introducing complementary, iron rich foods beginning around 4-6 months of age

- After 6 months of age:

- Continue to breastfeed

- Limit formula or milk feedings to 450mL to 600mL (15 to 20oz) per day

- Limit juice to 120mL (4 oz) per day, and always prefer water to juice

- Limit salt and sugar in food (added sugar should represent less than 10% of total calories)

- Serve home-prepared foods, and limit fast-food

- Respect normal variation in appetite without forcing children to finish their plate

- Give appropriate portion size

- Do not use food as a punishment or reward

- Eat meals together, with family and friends

- Avoid eating in front of the TV

Health professionals may also use the Harvard Healthy Eating Plate & Healthy Eating Pyramid (available in more than 30 different languages) as an additional tool to guide patients and help them adopt healthier nutrition habits.

Physical activity

The CPS has a position statement on developmentally appropriate strategies for encouraging physical activity and reducing sedentary time (particularly screen time) in children and youth.56 The CPS recommendations regarding physical activity are in line with the WHO’s guidelines that indicate that children aged 5-17 should perform at least 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity daily.3 When looking at the relationship between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and health outcomes, there is no evidence of a variation between ethnicities.57 A good way to promote physical activity in the immigrant population is to encourage family participation in community or culturally-based activities (e.g., traditional dance) or sports that are popular internationally (e.g., soccer). Activities where tax compensation is offered should also be encouraged.

Sleep

Establishing good sleep habits can help other routines, such as mealtimes, become more predictable and regular. Well rested children and teens will have more positive energy to give to physical activities. Shorter sleep durations in infancy and childhood are associated with a higher obesity risk.58 Food choices are often influenced by the lack of sleep and lack of a healthy daily routine 59 Minimizing screen time also has an impact on sleep patterns, the level of physical activity and ultimately the development of overweight and obesity. The Canadian Society of Pediatrics presents guidelines on screen time in young children.

What health professionals can do

Ask for a parent’s views on food, eating and weight, to better understand a family’s beliefs and to help negotiate a prevention or treatment plan. For example:

- Ask about the family’s background. Obesity is not considered a disease in many cultures. If deprivation was the norm in their country of origin, parents may continue practices that promote weight gain.25

- Assess the parent’s knowledge and beliefs about child health and disease by eliciting their vision of the health system. This approach can provide valuable information about perceptions they may have on obesity and other health issues. Parents may not be aware of the risks of obesity or the importance of following a treatment regimen. They might rely on a child’s ‘growing out’ of overweight naturally or believe that lifestyle changes will make little difference.23

- Explore and evaluate social supports, family roles and responsibilities, and a parent’s readiness to change. Extended family members can play an important role, especially if they resist or challenge a parent’s efforts to manage diet. Consider asking: Who cares for the child when the parents are not around? Who prepares the child’s meals? Who lives with the child?23

- Ask about breast and bottle feeding practices, as appropriate, and about introducing first complementary foods (what and when).23

- Assess the family’s intake of carbohydrates and beverages, as well as nutritional quality, and gauge the acceptability of making substitutions.23 Helpful information on common foods and feeding practices in different countries is available from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

- Assess parental attitudes to diet, physical activity, body size in children, media (e.g., TV), sleep.23

When applying culturally sensitive shared decision-making, it is recommended that health professionals acknowledge their own cultural values and remain aware of their own potential personal biases.60 The LEARN model61 is one framework for teaching cultural competence that is action-oriented and focuses on what health care providers can do:

- Listen with sympathy and understanding to the patient’s perception of a problem

- Explain your own perception of a problem

- Acknowledge and discuss differences and similarities

- Recommend treatment

- Negotiate agreement

Treating obesity

The treatment of obesity, just like its primary prevention, is focused on three main interventions: regular physical activity, a healthy diet, and adequate sleep. The Childhood Obesity Foundation, with its 5-2-1-0 rule,63 offers guidelines easy to follow (5 or more serving of vegetables or fruits per day, 2 hours of screening time or less per day, 1 hour of physical activity or more per day, 0 sugar sweetened beverages per day).

A family-centered approach and supportive home environment are important for encouraging and reinforcing lifestyle changes. Practitioners may want to consider family counselling and behavioural therapy with ongoing follow-up in complex cases.62 Multi-component behaviour-changing interventions (behaviour change, physical activity, diet) have been associated with decreased BMI in children and youth.63 Coordination with childcare or school programs can be helpful. Addressing mental health stressors is often a key component of global treatment and patient support.

Different pharmacological options approved by Health Canada (ex.: Orlistat, Liraglutide) are used in some adults as part of the treatment of obesity. There are no clear recommendations for their use in children and youth before puberty.

Conclusion

Studies suggest that the an immigrant’s risk of becoming overweight or obese increases with time lived in the new country,17,19 along with the long-term consequences of these conditions, such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.26 The need for ongoing follow-up and regular assessment is important.

Vignette

Julio, a 10-month old baby, is seen for his first examination in Canada, accompanied by his mother. His family emigrated from Mexico a month ago, and are now permanent residents. Julio’s father is job-hunting.

The family history reveals the presence of hyperlipidemia, without obesity, on the paternal side.

Although pregnancy with Julio and his term delivery were uneventful, Julio’s mother followed the advice of friends and stopped breastfeeding after only a week. She started formula-feeding because it was believed to be more practical and “modern”.

Julio drinks about 750 mL (25 oz)/day of whole milk and 480 mL (10 oz)/day of juice. He has started cereals and fruits but refuses vegetables and meat. When you ask, the mother mentions her fear of taking him outside in the winter cold. The clinical exam and the growth curves (weight, length and a weight-for-length ratio between the 3rd and 85th percentiles) are normal.

Learning points:

- Breast milk is the best food you can offer your baby and may help protect children from obesity. Health Canada and the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) recommend exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months of age. Breastfeeding can be continued until 2 years old or beyond. Babies should not start eating solid foods until about 4-6 months. More information on promoting breastfeeding among immigrant mothers is available in this resource.

- Vitamin D and iron are essential for healthy growth and development. Parent information on Vitamin D and Iron is available from the CPS.

- Nutrition guidance consistent with traditional eating customs needs to be provided. Information for parents is available from the CPS and Health Canada.

- Encourage family activity and outdoor play.

- Clinicians need to follow WHO growth charts (0-2 years) to assess children adequately.

- Use the routine schedule of immunization for regular check-up.

Vignette

Y

You next see Julio when he is about to start kindergarten, at 4 ½ years of age. The previous follow-ups were done at a local health center. His mother says he is very healthy, but he is now overweight according to the WHO growth curves.

The nutritional history reveals that Julio has become a ‘picky eater’ and that his family had to really encourage him to feed between 2 and 3 years of age. At present he eats little at breakfast (a glass of juice, a slice of toast with chocolate-nut spread). He has also been a fussy eater in childcare, disliking vegetables, salads and fruits and much preferring sweets. At home, Julio prefers American ‘fast food’ to homemade pozole, chilaquiles and huarache. His favourite drinks are juices and ‘refresco’. Julio’s mother is disappointed by some of his choices but is happy that he is adapting so well to his new country.

In general, he prefers to stay inside playing video games.

Learning points:

- A complete physical exam is important, with particular attention to blood pressure and oral health.

- Nutrition and healthy active living guidance needs to be reinforced with special attention to the four food groups and appropriate portions (using the Spanish version of the Harward Healthy Eating Plate & Healthy Eating Pyramid) as well as limiting screen time and encouraging physical activity.

- Ensure follow-up to support the family in these changes every 4 to 6 months.

Vignette

The next time we see Julio (11 years of age) is when he consults for a minor leg injury after being bullied in the schoolyard. Now in grade 6, he wants to play on the soccer team at school, but has not been able to make the try outs because of low endurance. According to the WHO curves for BMI, he is now clinically obese. His blood pressure is 135/85.

Learning points:

- A metabolic screening for diabetes and renal function and hypercholesterolemia is needed, as per Canadian guidelines.

- Investigate for hypertension. The U.S. National Institutes of Health has a quality resource on the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children.

- Implement a treatment plan and consider family-centred counselling on obesity-related risk factors. Use motivational interviewing and multidisciplinary approaches to reinforce new health messages and lifestyle changes.

- Refer Julio and his parents to supportive community resources concerned with bullying, and encourage them to discuss the problem with school officials.

- Identify underlying family stressors (especially economic) and make sure to connect the family with appropriate, supportive local services. Links to local community programs for immigrant and refugee families are available in this resource.

- More information is available from the CPS about psychosocial aspects of child and adolescent obesity.

- Schedule regular follow-up visits and document progress toward reaching a healthier weight and lifestyle changes every 4 to 6 months until transition to adult care.

Selected resources

- L’ABCDAIRE: GUIDE DE RÉFÉRENCE DU PRATICIEN 2012, Dépistage et prise en charge de l'obésité chez l'enfant, E. Rousseau.

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian physical activity guidelines and Canadian sedentary behaviour guidelines

- Caprio S, Daniels SR, Drewnowski A, et al. Influence of race, ethnicity, and culture on childhood obesity: Implications for prevention and treatment. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16 (12):2566-77.

- Dixon B, Peña MM, Taveras EM. Lifecourse approach to racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity. Adv Nutr 2012;3(1):73-82.

- The Griegg Health Record for children and adolescents aged 6-17 years.

- NutriSTEP: Nutrition screening tool for every preschooler

- The Rourke Baby Record for infants and children to 5 years of age.

- Satia JA. Dietary acculturation and the nutrition transition: An overview. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2010;35(2):219-23.

- WHO. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health.

- WHO. Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet No. 311. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2012

Information for parents

- CPS, How to promote good television habits, Tips for limiting screen time at home, and Physical activity for children and youth.

- Health Canada. Canada’s Food Guide. (Available in a number of languages.)

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Health promotion: Healthy living.

- Public Health England. Migrant health guide. Lifestyle factors and health promotion

Alternate Measures

Although the WHO growth curves are the only ones officially recommended, other growth charts can be useful. More information is available at: http://adoptmed.org/topics/growth-charts.html.

References

- Roberts KC, Shields M, deGroh M, Aziz A, Gilbert JA. Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: results from the 2009 to 2011 Canadian health measures survey. Health Rep. 2012:23(3): 37-41.

- Shields M, Tremblay MS. Canadian childhood obesity estimates based on WHO, IOTF and CDC cut-points. International Journal Pediatric Obesity. 2010:5:265-73.

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Acitivity and Health [Available from: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/.

- Rao DP, Kropac E, Do MT, Roberts KC, Jayaraman GC. Childhood overweight and obesity trends in Canada. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada. 2016; Volume 36.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014.

- Public Health England. Child weight data factsheet. London (UK). 2015; Report no. 2015432.

- Woo Baidal JA, Locks LM, Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Tavernas EM. Risk factors for childhood obesity in the first 1,000 days: a systematic review. American Journal of Pediatrics. 2016:50(6):761-79.

- Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obesity reviews: an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2008;9(5):474-88.

- McGuire S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md). 2012;3(1):56-7.

- Rose CM, Birch LL, Savage JS. Dietary patterns in infancy are associated with child diet and weight outcomes at 6 years. International journal of obesity (2005). 2017;41(5):783-8.

- Wallby T, Lagerberg D, Magnusson M. Relationship Between Breastfeeding and Early Childhood Obesity: Results of a Prospective Longitudinal Study from Birth to 4 Years. Breastfeeding medicine: the official journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. 201712:48-53.

- Cheng TS, Loy SL, Toh JY, Cheung YB, Chan JK, Godfrey KM, et al. Predominantly nighttime feeding and weight outcomes in infants. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2016;104(2):380-8.

- Hassink SG. Early Child Care and Education: A Key Component of Obesity Prevention in Infancy. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6).

- Uwaezuoke SN, Eneh CI, Ndu IK. Relationship Between Exclusive Breastfeeding and Lower Risk of Childhood Obesity: A Narrative Review of Published Evidence. Clinical medicine insights Pediatrics. 2017; 11: 1179556517690196.

- Block JP, Bailey LC, Gillman MW, Lunsford D, Daley MF, Eneli I, et al. Early Antibiotic Exposure and Weight Outcomes in Young Children. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6).

- Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Institute for Health Information. Obesity in Canada: A joint report. Ottawa. 2011.

- Goel MS, McCarthy EP, Philips RS, et al. Obesity among US immigrant subgroups by duration of residence. JAMA. 2004;292(23):2860-7.

- Buscemi J, Beech BM, Relyea G. Predictors of obesity in Latino children: acculturation as a moderator of the relationship between food insecurity and body mass index percentile. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2011;13(1):149-54.

- Fu H, VanLandingham MJ. Disentangling the effects of migration, selection and acculturation on weight and body fat distribution: results from a natural experiment involving Vietnamese Americans, returnees, and never-leavers. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2012;14(5):786-96.

- Crocker MK, Yanovski JA. Pediatric obesity: etiology and treatment. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2011;58(5):1217-40, xi.

- Han JC, Lawlor DA, Kimm SY. Childhood obesity. Lancet (London, England). 2010;375(9727):1737-48.

- Wojcicki JM, Young MB, Perham-Hester KA, de Schweinitz P, Gessner BD. Risk factors for obesity at age 3 in Alaskan children, including the role of beverage consumption: results from Alaska PRAMS 2005-2006 and its three-year follow-up survey, CUBS, 2008-2009. PloS one. 2015;10(3): e0118711.

- Pena MM, Dixon B, Taveras EM. Are you talking to ME? The importance of ethnicity and culture in childhood obesity prevention and management. Childhood obesity (Print). 2012;8(1):23-7.

- Pagani LS, Huot C. Why are children living in poverty getting fatter? Paediatrics & child health. 2007;12(8):698-700.

- Cheah CS, Van Hook J. Chinese and Korean immigrants' early life deprivation: an important factor for child feeding practices and children's body weight in the United States. Social science & medicine (1982). 2012;74(5):744-52.

- Rondinelli AJ, Morris MD, Rodwell TC, Moser KS, Paida P, Popper ST, et al. Under- and over-nutrition among refugees in San Diego County, California. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2011;13(1):161-8.

- Singh GK, Kogan MD, Yu SM. Disparities in obesity and overweight prevalence among US immigrant children and adolescents by generational status. Journal of community health. 2009;34(4):271-81.

- Harris KM, Perreira KM, Lee D. Obesity in the transition to adulthood: predictions across race/ethnicity, immigrant generation, and sex. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2009;163(11):1022-8.

- Quon EC, McGrath JJ, Roy-Gagnon MH. Generation of immigration and body mass index in Canadian youth. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2012;37(8):843-53.

- Wang S, Quan J, Kanaya AM, Fernandez A. Asian Americans and obesity in California: a protective effect of biculturalism. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2011;13(2):276-83.

- Singh RK, Kumar P, Mahalingam K. Molecular genetics of human obesity: A comprehensive review. Comptes rendus biologies. 2017;340(2):87-108.

- Chen JL, Weiss S, Heyman MB, Lustig R. Risk factors for obesity and high blood pressure in Chinese American children: maternal acculturation and children's food choices. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2011;13(2):268-75.

- Vasudevan D, Stotts A, Anabor OL, Mandayam S. Primary care physician's knowledge of ethnicity-specific guidelines for obesity diagnosis and readiness for obesity intervention among South Asian Indians. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2012;14(5):759-66.

- Brophy S, Cooksey R, Gravenor MB, Mistry R, Thomas N, Lyons RA, et al. Risk factors for childhood obesity at age 5: analysis of the millennium cohort study. BMC public health. 2009; 9: 467.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003-2006. Jama. 2008;299(20):2401-5.

- Sniderman AD, Bhopal R, Prabhakaran D, Sarrafzadegan N, Tchernof A. Why might South Asians be so susceptible to central obesity and its atherogenic consequences? The adipose tissue overflow hypothesis. International journal of epidemiology. 2007;36(1):220-5.

- Renzaho AM, Gibbons C, Swinburn B, Jolley D, Burns C. Obesity and undernutrition in sub-Saharan African immigrant and refugee children in Victoria, Australia. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition. 2006;15(4):482-90.

- Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutrition reviews. 2012;70(1):3-21.

- Phipps SA, Burton PS, Osberg LS, Lethbridge LN. Poverty and the extent of child obesity in Canada, Norway and the United States. Obesity reviews: an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2006;7(1):5-12.

- Health Canada CPS, Dietitians of Canada, Breastfeeding Committee for Canada; Infant Feeding Joint Working Group, 2012. [Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/infant-feeding/nutrition-healthy-term-infants-recommendations-birth-six-months.html.

- Van Hook J, Balistreri KS. Immigrant generation, socioeconomic status, and economic development of countries of origin: a longitudinal study of body mass index among children. Social science & medicine (1982). 2007;65(5):976-89.

- Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Obesity in Children (2015) [Available from: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/guidelines/published-guidelines/obesity-in-children/.

- Lawrence S, Cummings E, Chanoine JP, Metzger DL, Palmert M, Sharma A, et al. Canadian Pediatric Endocrine Group extension to WHO growth charts: Why bother? Paediatrics & child health. 2013;18(6):295-7.

- World Health Organization. The Asia-Pacific perspective: Redefining obesity and its treatment. Geneva Switzerland: WHO. 2010.

- Lau DC, Douketis JD, Morrison KM, et al. Obesity Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Panel. Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children. CMAJ. 2007; 176(8): S1-13.

- Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128 Suppl 5: S213-56.

- Styne DM, Arslanian SA, Connor EL, Farooqi IS, Murad MH, Silverstein JH, et al. Pediatric Obesity-Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2017;102(3):709-57.

- Panagiotopoulos C, Hadjiyannakis S, Henderson M. Type 2 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents. Canadian journal of diabetes. 2018;42 Suppl 1: S247-s54.

- Saunders NR, Gill PJ, Holder L, Vigod S, Kurdyak P, Gandhi S, et al. Use of the emergency department as a first point of contact for mental health care by immigrant youth in Canada: a population-based study. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2018;190(40): E1183-e91.

- Geserick M, Vogel M, Gausche R, Lipek T, Spielau U, Keller E, et al. Acceleration of BMI in Early Childhood and Risk of Sustained Obesity. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;379(14):1303-12.

- Bhaskaran K, Dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Douglas IJ, Smeeth L. Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study of 3.6 million adults in the UK. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology. 2018;6(12):944-53.

- Owen J. Childhood obesity: government's plan targets energy drinks and junk food advertising. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2018; 361: k2775.

- Dhana K, Haines J, Liu G, Zhang C, Wang X, Field AE, et al. Association between maternal adherence to healthy lifestyle practices and risk of obesity in offspring: results from two prospective cohort studies of mother-child pairs in the United States. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2018; 362: k2486.

- Critch JN. Nutrition for healthy term infants, six to 24 months: An overview. Paediatrics & child health. 2014;19(10):547-52.

- Leung AK, Marchand V, Sauve RS. The 'picky eater': The toddler or preschooler who does not eat. Paediatrics & child health. 2012;17(8):455-60.

- Gushulak BD, Pottie K, Hatcher Roberts J, Torres S, DesMeules M. Migration and health in Canada: health in the global village. CMAJ. 2011;183(12): E952-8.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. 2018.

- Magee L, Hale L. Longitudinal associations between sleep duration and subsequent weight gain: a systematic review. Sleep medicine reviews. 2012;16(3):231-41.

- Screen time and young children: Promoting health and development in a digital world. Paediatrics & child health. 2017;22(8):461-77.

- Derrington SF, Paquette E, Johnson KA. Cross-cultural Interactions and Shared Decision-making. Pediatrics. 2018;142(Suppl 3): S187-s92.

- Berlin EA, Fowkes WC, Jr. A teaching framework for cross-cultural health care. Application in family practice. The Western journal of medicine. 1983;139(6):934-8.

- Lipnowski S, Leblanc CM. Healthy active living: Physical activity guidelines for children and adolescents. Paediatrics & child health. 2012;17(4):209-12.

- Mead E, Brown T, Rees K, Azevedo LB, Whittaker V, Jones D, et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese children from the age of 6 to 11 years. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017; 6: Cd012651.

Reviewer(s)

- Élisabeth Rousseau Harsany, MD

- Laurence Gariepy-Assal, MD

Last updated: July, 2019