Chagas Disease (American trypanosomiasis)

Key points

- Chagas disease is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi and transmitted in the feces of infected triatomine bugs, which defecate during or after taking a blood meal.

- The disease is endemic in Latin America.

- Children with acute infection are more likely to be symptomatic than adults.

- The acute phase may be asymptomatic or include nonspecific symptoms and signs.

- The chronic phase occurs 10 to 30 years later and may include cardiac or gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Congenital infection occurs in an estimated 5% to 10% of newborns of infected mothers.

- Screening of blood donors and blood is done to prevent transmission via blood and blood products.

- Diagnosis in the acute phase is by detecting the parasite in a blood smear; diagnosis in the chronic phase is by serology.

- Treatment with benznidazole or nifurtimox is recommended for all cases of congenital, acute and chronic Chagas disease in children and youth younger than 18 years of age.

Introduction

Chagas disease (also referred to as American trypanosomiasis) is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, commonly transmitted in the feces of infected triatomine bugs. These relatively large blood-sucking insects, sometimes called ‘kissing bugs’ (Figure 1), are found mainly in Central and Latin America and in the southern United States. The bugs defecate during and after taking a blood meal. The bitten person self-inoculates by inadvertently rubbing insect feces containing the parasite into a bite site or mucous membranes in the eyes or mouth. The disease can be transmitted congenitally, from an infected mother to her baby2 and (less commonly) by blood transfusion, an organ transplant or contaminated food and drink. Vertical transmission occurs in an estimated 5% to 10% of newborns of infected mothers.3

Figure 1. Adult female kissing bug of the species Triatoma rubida. Scale bar = 1 cm.

Photo credit: Reisenman CE, Lawrence G, Guerenstein PG, et al. Infection of kissing bugs with Trypanosoma cruzi, Tucson, Arizona, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2010;16(3). Photograph by C. Hedgcock.

Epidemiology

The WHO estimates that approximately 7 to 8 million people worldwide are chronically infected with T. cruzi. The primary reservoir is Latin America, where the disease is endemic.4 Data on the prevalence of Chagas disease in newcomers to Canada are limited, particularly in young newcomers. One study estimated that 3.5% of immigrants to Canada from Latin America were infected with the disease in 2006.5

Risk factors

Endemic areas include Mexico, Central America and South America.2 While parts of the southern U.S. have enzootic cycles of T. cruzi involving triatomine bugs and mammals, notably racoons, opossums and dogs, most Chagas cases occur in immigrants from other countries.4,6

Severity of infection

Initial infection may be asymptomatic. The disease has 2 phases of differing severity:2,6

- First (acute) phase: Occurs soon after infection, with mild nonspecific symptoms (see Table 1) that resolve over 2 to 3 months without treatment. Rarely, the illness is severe, causing myocarditis and/or meningoencephalitis, which can be fatal. Severe symptoms occur more often in children, the elderly and the immunocompromised.

- Second (chronic) phase: Most patients with chronic T. cruzi infection have no symptoms. This asymptomatic chronic phase is known as the ‘indeterminate’ form. However, in 20% to 30% of cases, serious progression occurs 10 to 30 years after the initial infection. In the symptomatic chronic phase, cardiac manifestations may occur, including Chagas myocardopathy with conduction system abnormalities, right bundle branch block, complete heart block or ventricular arrhythmias, or congestive heart failure. Gastrointestinal manifestations include megaesophagus, megacolon and weight loss.6

Clinical clues

The first (acute) and second (chronic) phases of Chagas disease are associated with different symptoms, summarized in Table 1.2,6

|

First phase: Acute symptoms |

Second phase: Chronic symptoms |

|---|---|

| May occur one or more weeks after infection and last 2 to 3 months | May occur 10 to 30 years after initial infection |

|

|

|

* Romaña's sign is a result of conjunctival contamination with triatomine feces. Source: Adapted from Government of Canada (Travel.gc.ca) Travelling Abroad, Travel Health and Safety, Diseases, American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease). |

|

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of Chagas disease is based on laboratory testing following consideration of a patient’s clinical findings and infection risk.7 In Canada, the National Reference Centre for Parasitology (NRCP) in Montreal is the resource to contact about Chagas testing. If a patient tests positive, household members should also be tested if they have had similar exposures to triatomine bugs.

Testing formats depend on the phase of suspected disease:7

First (acute) phase

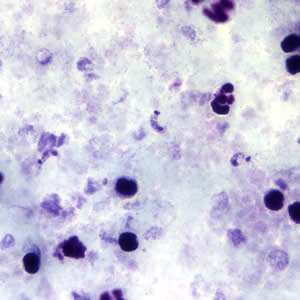

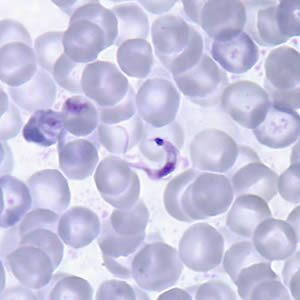

Identify circulating parasites (trypomastigotes) in a blood smear by microscopy (Figure 2). With central nervous system infections, trypomastigotes may be seen in cerebrospinal fluid.

Figure 2: T. cruzi trypomastigotes in a blood smear

Thick Smear

Thin Smear

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Image Library: http://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/trypanosomiasisAmerican/gallery.html#tcruzithin; http://dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/TrypanosomiasisAmerican.htm

Second (chronic) phase

Use 2 or more serological tests for antibody to the parasite (i.e., enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] and immunofluorescent antibody test [IFA]). Circulating parasite levels are generally undetectable during the chronic phase of infection.

Screening

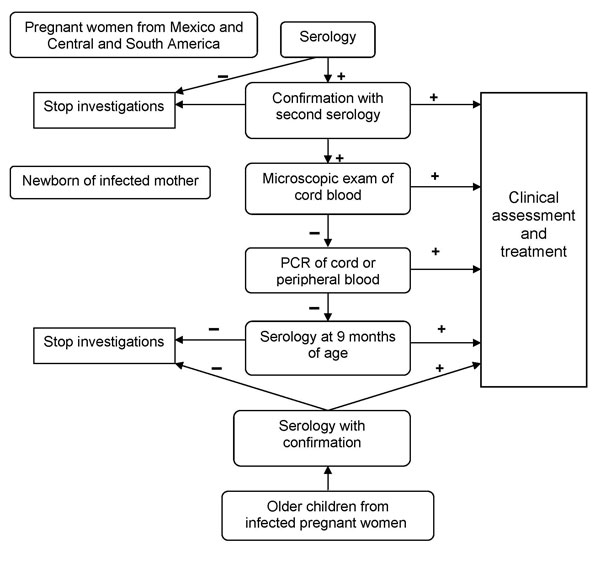

At-risk pregnant women, their newborns, and older children

All children of women with T. cruzi infection should be tested for Chagas disease.

Figure 3: Algorithm suggested by Geneva University Hospitals, Switzerland, for Pregnant Women from Latin America

Source: Jackson Y, Myers C, Diana A, et al. Congenital transmission of Chagas disease in Latin American immigrants in Switzerland. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15(4):601-3. With permission.

Blood donors and blood

Canadian Blood Services has added additional questions to the blood donor screening questionnaire to assess a donor’s potential risk of exposure to Chagas disease: ‘Have you spent at least 6 continuous months in Mexico, Central or South America?’ and ‘Were you or your mother or grandmother born in these regions?’ If donors answer ‘yes’ to either question, platelets and frozen plasma for transfusion are not produced from their blood and they are tested for the presence of T. cruzi antibodies. Infected adolescents are sometimes detected through screening when they volunteer to donate blood.

Treatment

Treatment for Chagas disease is recommended for all cases of congenital acute and chronic disease in children and adolescents younger than 18 years of age.6 The only antimicrobials proven to work are benznidazole and nifurtimox. Both drugs require special access through Health Canada. The disease can be cured if treatment is initiated soon after infection; however, the efficacy of treatment diminishes with increasing length of infection. Symptomatic treatment may also be required.4

Prevention

There is no vaccine against Chagas disease.2 Preventing triatomine bug bites is the best protection against Chagas disease when travelling or living in endemic regions:

- Do not camp or sleep outside,

- Avoid mud, palm thatch or adobe brick structures, which are vulnerable to infestation,

- Use insecticide-impregnated bed nets, and

- Examine living quarters for signs of infestation and exterminate if found.6

More information on preventing insect bites can be found in the Travel-Related Illness page of this resource.

Breastfeeding

Although data is limited, mothers with Chagas disease can continue to breastfeed unless they are in the acute phase of the disease, have reactivated disease due to immunosuppression, or have bleeding nipples.8

Selected resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites - American Trypanosomiasis (also known as Chagas Disease).

- Government of Canada. American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease).

- World Health Organization. Health topics: Chagas disease.

References

- Reisenman CE, Lawrence G, Guerenstein PG, et al. Infection of kissing bugs with Trypanosoma cruzi, Tucson, Arizona, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2010;16(3).

- Government of Canada. American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease).

- Jackson Y, Myers C, Diana A, et al. Congenital transmission of Chagas disease in Latin American immigrants in Switzerland. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15(4):601-3.

- World Health Organization. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). Fact sheet N°340. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO,updated March 2013.

- Schmunis GA, Yadon ZE. Chagas disease: A Latin American health problem becoming a world health problem. Acta Trop 2010;115(1-2):14-21.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. American trypanosomiasis(Chagas Disease). In: Pickering LL, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Elk Grove Village, IL: AAP, 2012:734-36.

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites — American Trypanosomiasis (also known as Chagas Disease). Diagnosis. July 2013.

- Norman FF, López-Vélez R. Chagas disease and breast-feeding. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19(10):1561-6.

Reviewer(s)

- Noni MacDonald, MD

Last updated: February, 2023