Female genital mutilation/cutting

Key points

- Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is a criminal offense in Canada.

- FGM/C is recognized as a harmful practice. It affects the physical and psychological well-being of girls and women, and has no medical benefit.

- The practice is typically performed at some point between infancy and age 15.

- Although FGM/C remains prevalent in many regions of the world, support for it varies among newcomers to Canada.

- Health care providers can play a key role by providing a respectful and culturally sensitive approach to history-taking and counselling. In order to do this, providers need to be thoughly aware of the medical and psychosocial consequences of this practice.

Terminology

Terms used in the medical literature include female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), female genital cutting, female genital mutilation and female genital circumcision. The term female genital mutilation/cutting is used by UNICEF and, in advocacy documents, the World Health Organization (WHO) generally uses the term female genital mutilation.1,2 However, women who have been cut, or mothers discussing the issue for their daughters, may use the terms ‘circumcision' or ‘cutting’.3

Because of the sensitivity surrounding the practice, it is important that clinicians speak to patients using language that is neutral and ethically sensitive. Information on an approach to prevention and counselling is provided below.

Specific terms include: 1,4,5

- Clitoridectomy: Partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce

- Infibulation: Excision of part of the external genitalia and stitching of the vulvo-vaginal opening

- Defibulation: Reopening the vulvo-vaginal opening in a woman who has previously undergone infibulation, for sexual intercourse or childbirth

- Reinfibulation: Stitching closed the vulvo-vaginal opening or labia following defibulation

- FGM/C: All procedures involving the partial or total removal of the external genitalia, or any other injury (i.e., pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, cauterization) to the genital organs for non-medical reasons

Legal issues

FGM/C is widely recognized by national and international organizations as a harmful practice that violates the human rights of girls and women.4,5 Legislation banning FGM/C has been passed in the majority of African countries.1

Performing FGM/C is a criminal offence in Canada. In its policy statement, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) advises that:4

- Performing or assisting with the practice of FGM/C in Canada is a criminal offence.

- Reporting to appropriate child welfare protection services is mandatory when it is suspected that a female child has been subjected to FGM/C or is at risk of being subjected to the practice.

- Requests for reinfibulation should be declined.

FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women. It reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes, and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women. It is nearly always carried out on minors and is a violation of the rights of children.2

The provincial colleges of physicians and surgeons in Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec have endorsed the WHO’s position on FGC/M. Their guidelines are listed in Selected resources.

More information is available in section 268 of the Criminal Code of Canada.

Global prevalence

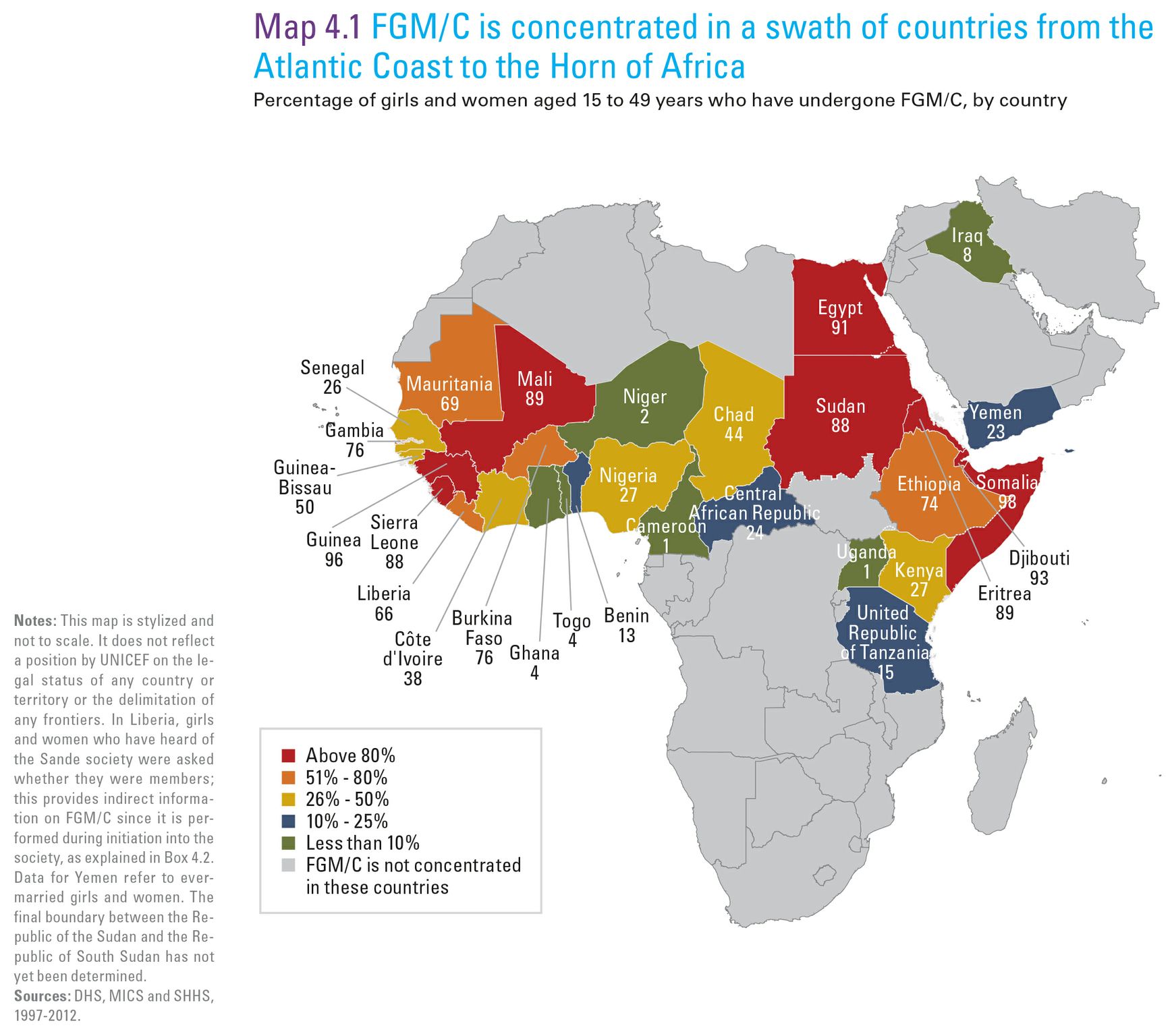

An estimated 125 million girls and women worldwide have experienced FGM/C.1 Most documented cases are concentrated in 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East,1 as shown in Figure 1. High prevalence of FGM/C occurs in North and East Africa (i.e., in Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan) and in some West African countries (Burkina Faso, the Gambia, Guinea and Mali).6 While the practice is also reported in India, Indonesia, Israel, Malaysia, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates,7 (WHO 2011), prevalence in these countries is unknown.

There is substantial variation in prevalence within and among countries. For example, FGM/C is almost universal in Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti and Egypt (> 90%), but affects only 1% of girls and women in Cameroon and Uganda.1 Higher prevalence countries tend to have less within-country variation, while lower prevalence countries tend to have more regional variation. Heightened screening for girls and young women from countries with high prevalence is warranted. Screening girls and young women from lower-prevalence areas is also important but may be more challenging because of differing levels of support and regional variations in practice. In addition to Figure 1, UNICEF has a detailed infographic with data on FGM/C rates in Africa and the Middle East.

UNICEF reports that FGM/C is declining in the 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East, and particularly in countries where prevalence is already low to very low. However, no significant change has been reported in Chad, Djibouti, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Senegal, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen.1

|

Prevalence |

Countries |

|---|---|

|

Very high (>80%) |

Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Mali, Sierra Leone, Sudan |

|

Moderately high (51%-80%) |

Gambia, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Mauritania, Liberia |

|

Moderatley Low (26%-50%) |

Guinea-Bissau, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal |

|

Low (10%-25%) |

Central African Republic, Yemen, United Republic of Tanzania, Benin |

|

Very Low (<10%) |

Iraq, Ghana, Togo, Niger, Cameroon and Uganda |

|

Source: UNICEF, 2013. Female genital mutilation/cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change: 23. |

|

In Burkina Faso, 76% of girls and women have been cut, but only 9% favour continuing the practice.1

Prevalence in newcomer populations in Canada

The prevalence of FGM/C in newcomer populations is difficult to gauge,6 and Canadian data are lacking. The Ontario Human Rights Commission has identified evidence to indicate that FGM/C is practiced in Canada. Some families send their daughters out of Canada to have FGM/C performed.8

Based on census data from 2000, as many as 400,000 girls and women in the U.S. had immigrated from a country where they may have experienced FGM/C.9 Estimates in Europe are slightly higher, with 500,000 girls and women affected and 180,000 considered at risk due to country of origin or birth.7 One study of the Netherlands found that approximately 40% of 70,000 newcomer women from countries where FGM/C is traditionally practiced had undergone cutting.10 Whether FGM/C had been performed before or after migration was not reported.

In some communities, parental intentions regarding FGM/C for their daughters decline following immigration. However, the factors influencing their change in outlook are not fully understood.1 Health care providers should be aware that even in countries with a high prevalence of FGM/C, support for the practice varies substantially and should be sensitively explored with newcomers. More information is available in the counselling and support section of this page.

Misperceptions

There are numerous myths and misperceptions concerning FGM/C, including that the practice: 11,12

- Is supported or mandated by religion

- Is an important cultural tradition that should not be questioned or stopped, particularly not by outsiders

- Prepares a girl for adulthood and marriage

- Reduces a women’s sexual desire, preserves virginity and prevents promiscuity

- Improves male sexual pleasure and virility

- Facilitates childbirth by increasing a women’s pain tolerance

- Facilitates cleanliness

- Prevents the clitoris from growing excessively

Risk Factors

|

Age |

FGM/C is typically performed at some point between infancy and age 15 years. In half the 29 countries where FGM/C is most commonly practiced, >80% of cutting occurs in girls <5 years of age. |

|

Region |

Prevalence varies greatly among countries and there is also substantial variation within countries. Countries where the prevalence of FGM/C is highest (>80%) include Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Mali, Sierra Leone and Sudan. Data on prevalence by country is detailed in Figure 1. |

|

Religion |

The prevalence of FGM/C is highest among Muslim girls and women, but this is not always the case. FGM/C is also reported among individuals with other religious backgrounds. |

|

Urban vs. rural |

FGM/C prevalence tends to be lower in wealthy urban residents, perhaps because they have exposure to a greater number of socio-cultural networks. |

|

Economic status |

The prevalence of FGM/C is generally lower in relatively wealthier households. |

|

Education level of mother |

The prevalence of FGM/C is generally highest among daughters of women with no education. |

|

FGM/C in mother |

The chances that a girl will undergo FGM/C are significantly increased if her mother has been cut. |

|

Sources: Hearst AA, Molnar AM. Female genital cutting: An evidence-based approach to clinical management for the primary care physician. Mayo Clin Proc 2013;88(6):618-29; UNICEF, 2013. Female genital mutilation/cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change; Yoder PS, Wang S, Johansen E. Estimates of female genital mutilation/cutting in 27 African countries and Yemen. Studies in Family Planning 2013; 44(2):189-204. |

|

Types of FGM/C

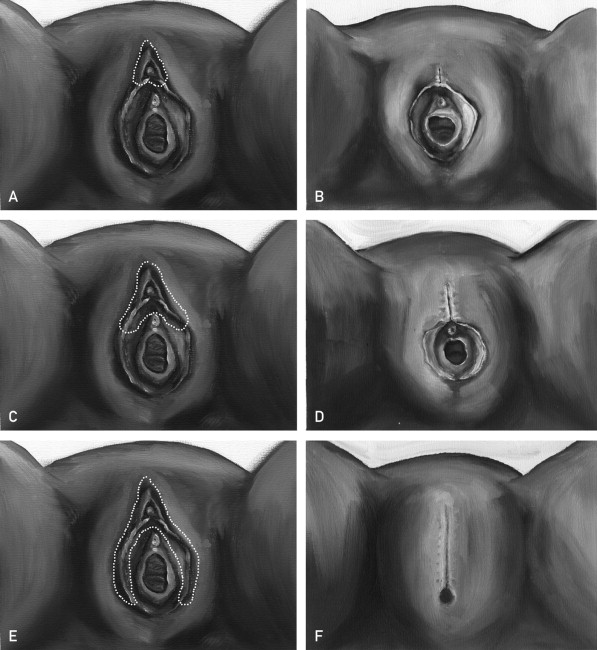

The WHO identifies 4 types of FGM/C,5 which are summarized in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 2.3

In Somalia, 63% of girls who underwent FGM/C had their genitalia sewn closed.1

Complications

FGM/C is recognized as harmful to girls and women, both physically and psychologically, and has no medical benefit.4 The occurrence of trauma and medical complications may relate to:3,4

- The type of FGM/C

- The type of practitioner

- The absence or misuse of anesthesia

- The type of equipment used (scissors, razor blades, and/or broken glass may be used)

FGM/C is widely performed by traditional practitioners, but health practitioners do perform the procedure in some regions of the world, and their involvement appears to be increasing 2. In Egypt, an estimated 77% of procedures are carried out by a doctor, nurse, midwife or other health worker.1

In Egypt, an estimated 77% of girls who have undergone FGM/C were cut by a medical professional, nearly always with an anaesthetic being used. By contrast, an estimated 97% of cases in Yemen underwent the procedure in their homes, and 75% of these girls were cut using a blade or razor. No information was conveyed regarding the use of an anesthetic in these settings.1

Early complications

Early complications are usually treated by a local practitioner, and patients may only present to a health care professional for complications that are significant or occur well after the procedure.3 Early complications include severe pain, bleeding, infection and urinary retention and are associated more frequently with FGM/C types 2 and 3, as shown above.3

Later complications

Later complications of FGM/C are summarized in Table 3.3

Evidence of the effect of FGM/C on fertility is mixed,3 but it can be affected long term by a number of factors, such as the physical barrier created by certain types of FGM/C, scarring or stenosis, and infections of the uterus or adnexa. FGM/C may be associated with psychological isues, such as dyspareunia and fear of sexual encounters, affective disorders, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and somatization.3 No randomized trials of the impact of FGM/C on pregnancy outcomes have been carried out to date.13

What health practitioners can do

Health care providers who see newcomer girls and adolescents in their practice should be aware of FGM/C and be ready to provide culturally sensitive, clinically informed care, including early recognition and management of the complications. Patients may present with an early complication of FGM/C, but in Canada they are more likely to present with later problems.3 A health provider should treat such cases as per standard practice, but may also need to make appropriate investigations and enlist specialist support. Clinicians can play a key role to ensure that women who have undergone this procedure receive proper care and support by:

- Informing themselves about this practice, asking questions, and gauging the level of support and perspectives on FGM/C in families they see.

- Being open to discussing this issue with patients and families.

- Providing counselling and support or appropriate referrals for girls/adolescents and their parents, as needed. The SOGC notes that adequate and respectful counselling or support might entail involving a culturally competent interpreter or social worker.4

- Revisiting the issue. Not all patients or families will be open to counselling on such a personal topic at the first clinical encounter. Raising the issue again, once a relationship of trust is established, is likely to be more effective.

- Offering physical examination of genetalia as part of screening.

- Performing physical examination in a sensitive manner, when consent is obtained, to identify presence and type of FGM/C and any complications (particularly infection, labial fusion/vaginal stenosis and keloids or other evidence of scarring). Guidance for genital examination of paediatric patients is available in this Pediatrics in Review article.14

- Recognizing and treating complications.

- Prevention. Questions to consider asking a newcomer patient or her family are listed below.15 A sensitive introduction is important. Consider some version of this approach: ‘I would like to discuss a very personal aspect of your daughter’s health with you – called circumcision or cutting – Do you mind if we speak about this?.’ 'Is circumcision a common practice in your country? In your family? Are you comfortable sharing your thoughts and feelings about this practice?'

Possible questions to consider:

- Family (maternal) history: Have the women in your family (your mother or grandmother) been circumcised? If so, please share your experience. Where was it done? By whom? What was your age at circumcision? How do women in your family feel about circumcision?

- Community/context: Do you talk about circumcision with other women? Your daughters? Do you know anyone who is not circumcised? What have you heard?

- Beliefs: What do you think is good about being circumcised? What are the troublesome aspects of being circumcised? Does your religion recommend circumcision? Is circumcision for women normal in your culture or family?

- Plans/concerns: How would you feel about your daughters not being circumcised in Canada ? How do you think your daughter would feel if she is not circumcised? How do you think your daughter’s future husband would feel if your daughter is not circumcised?

- Difficult scenarios: Do you hope to be able to circumcise your daughter? In Canada, circumcision is not legal, how does that affect your plans? Are you aware of the laws relating to circumcision in Canada?

For patients who have already experienced FGM/C

Discussing FGM/C with girls/adolescents and their parents can be challenging. Still, studies generally show that most women who have had FGM/C would like their physician to discuss the topic with them in a proactive way: that is, when it pertains to a current or anticipated health or family problem. 3 Possible questions:

- Do you (or your daughter) have any pain/discomfort/problems because of this procedure ? Are there any other problems or feelings you would like to share? And especially: What medical help would you like for any of these problems?

"When the physician (rather than the patient) initiates the questions in a way that is normalized as part of the overall woman’s health history, it can help to overcome the patient’s or the interpreter’s embarrassment about the topic." (Hearst 2013)

Selected resources

- Hearst AA, Molnar AM. Female genital cutting: An evidence-based approach to clinical management for the primary care physician. Mayo Clin Proc 2013;88(6):618-629.

- Senikas, V, Davis, V, Perron L, Burnett, M. Clinical Practice Guideline: Female Genital Cutting. November 2013, SOGC

sogc.org/guidelines/clinical-practice-guideline-female-genital-cutting/ - Sauer PJ, Neubauer D. Female genital mutilation: a hidden epidemic (statement from the European Academy of Paediatrics). Eur J Pediatr 2014; 173: 237-238.

- UNICEF. Infographic on FGM/C in Africa and the Middle East.

- UNICEF FGC page (including links to resources):

- UNICEF Publication: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change.

- UNICEF resource: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting country profiles

- United Nations General Assembly. 67/146. Intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilations Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 20 December 2012. http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/67/146

- WHO. Female genital mutilation. http://www.who.int/topics/female_genital_mutilation/en/

- WHO. Female genital mutilation: Integrating the prevention and management of the health complications into the curricula of nursing and midwifery. A teacher’s guide. WHO, 2001. http://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/FGM_Teachers%20Guide_English.pdf

- WHO. Eliminating female genital mutilation: an interagency statement. An interagency statement by OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2008:22-7. Available at: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/fgm/9789241596442/en/index.html

Provincial College Guidelines:

- The College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia: Professional Standards and Guidelines Female Genital Mutilation

- The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario: Female Genital Cutting (Mutilation)

- Collège des Médecins du Québec: Request for Female Genital Mutilation

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia: Policy Regarding Female Genital Mutilation

References

- UNICEF. Female genital mutilation/cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. New York, NY: UNICEF, 2013: www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf

- WHO. Female genital mutilation. Fact sheet N°241. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2014:

- Hearst AA, Molnar AM. Female genital cutting: An evidence-based approach to clinical management for the primary care physician. Mayo Clin Proc 2013;88(6):618-29.

- Perron L, Senikas V, Burnett M, et al. Female genital cutting. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35(11): 1028-45: sogc.org/guidelines/clinical-practice-guideline-female-genital-cutting/

- WHO. Eliminating female genital mutilation: An interagency statement by OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2008:22-7: www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/fgm/9789241596442/en/index.html

- Yoder PS, Wang S, Johansen E. Estimates of female genital mutilation/cutting in 27 African countries and Yemen. Studies in Family Planning 2013; 44(2):189-204.

- WHO. An update on WHO’s work on female genital mutilation (FGM): Progress report. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2011.

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. FGM in Canada: www.ohrc.on.ca/en/policy-female-genital-mutilation-fgm/4-fgm-canada

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 2013. Female genital cutting -- Ancestry diagram:

- Exterkate M. Female genital mutilation in the Netherlands: Prevalence, incidence and determinants. Utrecht, The Netherlands: PHAROS; 2013: www.pharos.nlhttps://kidsnewtocanada.ca/uploads/documents/doc/vrouwelijkegenitaleverminkinginnederland-finalreportfgminnl1.pdf

- WHO. Understanding and addressing violence against women. Female genital mutilation. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2012.

- WHO. Female genital mutilation: Integrating the prevention and management of the health complications into the curricula of nursing and midwifery. A teacher’s guide. WHO, 2001. http://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/FGM_Teachers%20Guide_English.pdf

(This link provides year of publication http://www.k4health.org/toolkits/igwg-gender/female-genital-mutilation-integrating-prevention-and-management-health) - Balogun OO, Hirayama F, Wariki WM, Koyanagi A, Mori R. Interventions for improving outcomes for pregnant women who have experienced genital cutting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:CD009872.

- Jacobs A, Alderman E. Gynecologic examination of the prepubertal girl. Pediatrics in Review 2014;35(3):97-105.

- Upvall MJ, Mohammed K, Dodge PD. Perspectives of Somali Bantu refugee women living with circumcision in the United States: a focus group approach. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46(3):360-368.

Reviewer(s)

- Andrea Hunter, MD

Last updated: January, 2016