How Culture Influences Health

Key points

- Culture is a pattern of ideas, customs and behaviours shared by a particular people or society. It is constantly evolving.

- The speed of cultural evolution varies. It increases when a group migrates to and incorporates components of a new culture into their culture of origin.

- Children often struggle with being ‘between cultures’– balancing the ‘old’ and the ‘new’. They essentially belong to both, whereas their parents often belong predominantly to the ‘old’ culture.

- One way of thinking about cultures is whether they are primarily ‘collectivist’ or ‘individualist’. Knowing the difference can help health professionals with diagnosis and with tailoring a treatment plan that includes a larger or smaller group.

- The influence of culture on health is vast. It affects perceptions of health, illness and death, beliefs about causes of disease, approaches to health promotion, how illness and pain are experienced and expressed, where, when and how patients seek help, and the types of treatment patients prefer.

- Culture could influence socio-economical status and thus dictate psychosocial coping mechanism or response.

- Both health professionals and patients are influenced by their respective cultures. Canada’s health system has been shaped by the mainstream beliefs of historically dominant cultures.

- Cultural bias may result in very different health-related preferences and perceptions. Being aware of and negotiating such differences are skills known as ‘cultural competence’. This perspective allows care providers to ask about various beliefs or sources of care specifically, and to incorporate new awareness into diagnosis and treatment planning.

- Demonstrating awareness of a patient’s culture can promote trust, better health care, lead to higher rates of acceptance of diagnoses and improve treatment adherence.

What is culture?

Culture is the patterns of ideas, customs and behaviours shared by a particular people or society. These patterns identify members as part of a group and distinguish members from other groups. Culture may include all or a subset of the following characteristics:1,2

Given the number of possible factors influencing any culture, there is naturally great diversity within any cultural group. Generalizing specific characteristics of one culture can be helpful but be careful not to over-generalize. Culture is:

- ethnicity

- language

- religion and spiritual beliefs

- gender

- socio-economic class

- age

- sexual orientation

- geographic origin

- group history

- education

- upbringing

- life experience

Culture is:

- dynamic and evolving,

- learned and passed on through generations,

- shared among those who agree on the way they name and understand reality,

- often identified ‘symbolically’, through language, dress, music and behaviours, and

- integrated into all aspects of an individual’s life.3

Case examples

Compare the two stories that follow and imagine how each child might react differently to a similar situation, such as a problem at school, a criticism, or their mother becoming ill.

A great escape?

A 10-year-old Sudanese girl lived for 3 years as the less-cared-for child with an aunt who had 4 other children. Her mother, a Sudanese journalist, was persecuted and jailed after having written politically sensitive articles in a national newspaper. One night, her mother suddenly arrived to take the child away under cover of darkness. They walked all night and slipped across the border. Once across, they lived in a refugee camp for 2 years, facing various difficulties because they had no male family member to protect them. Eventually, with assistance from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the Canadian government, they made their way to Canada as Government Assisted Refugees. The mother has since been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, and although she is being treated, she has difficulty functioning in the day-to-day and adapting to life in Canada. The daughter quickly became her mother’s interpreter and caregiver. She appeared well-adapted, did well in school, was motivated to help her mother, smiled and spoke easily and was very intent on learning English. No one thought to ask how she had dealt with her own story.

Turning the page

A 10-year-old daughter of a Sudanese schoolteacher in a wealthy area of Khartoum left the country with her mother under the protection of a diplomat during a stable period. This diplomat had arranged visas to Germany and provided a car with diplomatic license plates and a skillful driver, who drove them to the safest airport. There, they boarded a small plane that connected to a pre-arranged flight to Frankfurt, Germany. Mother and daughter lived for two years in Frankfurt, the child attending school while her mother worked as a tutor. They rented a room from a friend. Ultimately, they decided to migrate to Canada to join extended family in Toronto, who sponsored them. The mother remarried after arriving in Canada.

Learning points:

- Diversity exists within any single culture.

- The adaptation of a child can be influenced by numerous factors in addition to culture (personal, family, migration-related, social, environmental).2

- Any negative effects of such factors may be well hidden by the child.

- A child may compensate for a parent’s debility.

- Migration trajectories vary in significant ways.

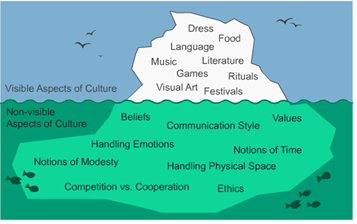

Culture: The hidden and the obvious

Culture has been described as an iceberg, with its most powerful features hidden under the ocean surface as illustrated in Figure 1. Explicit cultural elements are often obvious but possibly less influential than the unrecognized or subconscious elements providing ballast below.

| Figure 1: Elements of culture |

|

| Source: Slide 6, Introduction to clinical cultural competence. Clinical Cultural Competency Series. Courtesy of the Centre for Innovation & Excellence in Child & Family Centred Care at SickKids Hospital. |

The cultural continuum

Culture is commonly divided into two broad categories at opposite ends of a continuum: collectivistic or individualistic. Most cultures fall somewhere between the two poles, with characteristics of both. Also, within any given culture, individual variations range across the spectrum. Still, being familiar with characteristics of collectivistic and individualistic cultures is useful (see Table 1) because it helps practitioners to ‘locate’ where a family falls within their cultural continuum and to personalize patient care.

Collectivistic and individualistic cultures can give rise to different views on human health, as well as on treatment, diagnoses and causes of illness. Depending on where a patient ‘fits’ along their cultural continuum, including extended family in discussions about disease origin, diagnosis and treatment may be helpful. Consent for certain diagnostic and therapeutic interventions may be needed from extended family members.

Indecision or decision-making?

You might expect a 26-year-old mother to make a decision regarding her child’s treatment alone. Having just completed an evaluation of her 6-year-old, you present 2 options for investigation. The mother shies away from making a firm decision and answers you in vague terms. She seems to speak in circles, almost dancing around the choice, even after hearing all the information needed to decide which care path to follow. You know that she has finished high school, and note impatiently that you have already spent an hour with her. The following week she returns. You worry about the length of the visit and falling behind with other patients. To your surprise, she is decisive. She confides, with some prompting, that she discussed treatment options with her husband and mother-in-law, and together they have arrived at the best solution. She can now confidently pursue the investigation of her child’s condition.

Learning points:

- The health care provider’s culture is individualistic, while the mother’s is more collectivistic. The mother needed to consult before she could provide an answer.

- Communication styles differ. The mother feared shaming the provider by doubting advice, but also didn’t feel comfortable admitting that she would have to bring the choice home to decide.

- Education level is not an issue: it’s a red herring.

Impact of culture on health

Health is a cultural concept because culture frames and shapes how we perceive the world and our experiences. Along with other determinants of health and disease, culture helps to define:

- How patients and health care providers view health and illness.

- What patients and health care providers believe about the causes of disease. For example, some patients are unaware of germ theory and may instead believe in fatalism, a djinn (in rural Afghanistan, an evil spirit that seizes infants and is responsible for tetanus-like illness), the 'evil eye', or a demon. They may not accept a diagnosis and may even believe they cannot change the course of events. Instead, they can only accept circumstances as they unfold.

- Which diseases or conditions are stigmatized and why. In many cultures, depression is a common stigma and seeing a psychiatrist means a person is “crazy”.

- What types of health promotion activities are practiced, recommended or insured. In some cultures being “strong” (or what Canadians would consider “overweight”) means having a store of energy against famine, and “strong” women are desirable and healthy.

- Cultural norms can influence how individuals express pain and how healthcare professionals respond to or manage it. By inquiring about a patient’s beliefs regarding pain, as well as their preferences for incorporating traditional healing practices (e.g., spiritual rituals), healthcare providers can optimize pain management in a culturally sensitive manner.4

- Where patients seek help, how they ask for help and, perhaps, when they make their first approach. Some cultures tend to consult allied health care providers first, saving a visit to the doctor for when a problem becomes severe.

- Patient interaction with health care providers. For example, not making direct eye contact is a sign of respect in many cultures, but a care provider may wonder if the same behaviour means her patient is depressed.

- The degree of understanding and compliance with treatment options recommended by health care providers who do not share their cultural beliefs. Some patients believe that a physician who doesn’t give an injection may not be taking their symptoms seriously. Some patients also believe that any medical management without the use of intravenous fluids (I.V fluids) is incomplete.

- How patients and providers perceive chronic disease and various treatment options.

Culture also affects health in other ways, such as:

- Acceptance of a diagnosis, including who should be told, when and how.

- Acceptance of preventive or health promotion measures (e.g., vaccines, prenatal care, birth control, screening tests, etc.).

- Perception of the amount of control individuals have in preventing and controlling disease.

- Perceptions of death, dying and who should be involved.

- Use of direct versus indirect communication. Making or avoiding eye contact can be viewed as rude or polite, depending on culture.

- Willingness to discuss symptoms with a health care provider, or with an interpreter being present.

- Influence of family dynamics, including traditional gender roles, filial responsibilities, and patterns of support among family members.

- Perceptions of youth and aging.

- How accessible the health system is, as well as how well it functions.

What can health professionals do?

Health care providers are more likely to have positive interactions with patients and provide better care if they understand what distinguishes their patients’ cultural values, beliefs and practices from their own.

The following suggestions may help you care for and communicate with patients who are new to Canada:5,6

- Consider how your own cultural beliefs, values and behaviours may affect interactions with patients. If you suspect an interaction has been adversely affected by cultural bias – your own or your patient’s – consider seeking help.

- Respect, understand and work with differing cultural perceptions of effective or appropriate treatment. Ask about and record how your patients like to receive health care and treatment information.

- Where needed, arrange for an appropriate interpreter.

- Listen carefully to your patients and confirm that you have understood their messages exactly.

- Make sure you understand how the patient understands his or her own health or illness.

- Recognize that families may use complementary and alternative therapies. For appropriate, specific conditions, remind them that complementary and alternative medicine use can delay biomedical testing or treatment and potentially cause harm.

- Try to ‘locate’ the patient in the process of adapting to Canadian culture. Assess their support system. What are their language skills?

- Negotiate a treatment plan based on shared understanding and agreement.

- In Canada, health information is typically print-based. Find out whether a patient or family would benefit from spoken or visual messaging for reasons of culture or limited literacy.

Read more about cultural competence, including specific strategies for delivering culturally competent care. Helpful tools and resources are available from other sources. SickKids Hospital in Toronto has created a series of e-learning modules. You may wish to complete two modules in particular: Cross-Cultural Communication and Parenting Across Cultures.

Providing health care to different cultural groups

Developing a guide to help health professionals understand cultural preferences and characteristics around the world would be a mammoth undertaking. Also, any such document would be biased by the authors’ own cultural perspectives. Culturally, health professionals in Canada are increasingly diverse, viewing the world and the people they see through many different lenses.

However, health care providers should learn skills around cultural competence and patient-centred care. Such skills can be a compass for exploring, respecting and using cultural similarities and differences to improve quality of care and patient outcomes.

Above all, key tenants include:

- Cultures are dynamic.

- There is huge diversity within any culture.

- Even when you think you understand one culture, it will have evolved or you will have identified exceptions.

As a step further, understanding intersectionality and structural inequities should be recognized by child health providers:

- Intersectionality describes how various identities (e.g., immigration status, income level, gender identity) intersect to determine social location, which influences health and health care access. To provide culturally sensitive care, it is important to examine how intersecting identities influence a child’s health care needs.7

- Recognition and dismantling of system-level inequities in healthcare are critical steps to provide culturally sensitive care (e.g., it is important to acknowledge overcrowded housing and poor air quality as factors influencing asthma management of a newcomer child). Institutional and policy level changes are needed to address structural inequities.7

Resources

- Additional Cultural Competency Tools and Resources

- Coverdell, Paul D. World wise schools: Culture matters workbook: Thirteen cultural categories; American and host country views compared. Peace Corps.

- Juckett, Gregory. Cross cultural medicine. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(11):2267-74.

- SickKids Hospital (Toronto, Ontario), Centre for Innovation and Excellence in Child and Family-centred Care. The Clinical Cultural Competence E-Learning Modules Series.

References

- University of Minnesota, Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition. What is culture?

- Miyamoto, Yuri, and Ryff, Carol. “Culture and Health: Recent Developments and Future Directions.” Japanese Psychological Research, vol 64, no 2, 2022.pp 90-108

- Nova Scotia Department of Health, Primary Health Care Section, 2005. A cultural competence guide for primary health care professionals in Nova Scotia.

- Okolo, Chioma & Babawarun, Oloruntoba & Olorunsogo, Tolulope. (2024). Cross-Cultural Perspectives On Pain: A Comprehensive Review of Anthropological Research. International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences. 6. 303-315. 10.51594/ijarss.v6i3.888.

- Kodjo, C. Cultural competence in clinician communication. Paediatric Rev 2009; 30(2):57-64.

- University of Washington Medical Centre. Communication Guide: All Cultures. Culture Clue for Clinicians, 2011.

- William Okoniewski, Mangai Sundaram, Diego Chaves-Gnecco, Katie McAnany, John D. Cowden, Maya Ragavan; Culturally Sensitive Interventions in Pediatric Primary Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics February 2022; 149 (2): e2021052162. 10.1542/peds.2021-052162.

Reviewer(s)

Ryan Giroux, MD

Sana Gill, MD

Last updated: February, 2025