Gastrointestinal parasitic infections in immigrant and refugee children

Key points

-

Giardia, soil-transmitted helminthic (worm) infections (e.g., roundworm [Ascaris], whipworm [Trichuris] and hookworm), and parasites of the Strongyloides and Schistosoma species, are among the most common infections in refugee populations.

- While often asymptomatic or subclinical, these infections can also cause significant illness and even death.

- Screening with serological tests for Schistosoma species is recommended for newly arrived refugees and immigrants from endemic regions of the worlds, such as Africa. If results are positive, treatment is recommended even when children are asymptomatic.

- Screening with serological tests for Strongyloides stercoralis is recommended for newly arrived refugees and immigrants from endemic areas, such as Southeast Asia and Africa. If results are positive, treatment is recommended even when children are asymptomatic.

Roundworms (nematodes)

| Figure 1. Ascaris (roundworm) egg and adult female worm |

|

|

|

Source: Orange County Public Health |

Intestinal nematodes are transmitted to humans by one of two routes:

- Ingestion of soil contaminated with infective eggs (e.g., roundworm and whipworm [A. lumbricoides, T. trichiura])

- Penetration of skin with infective larvae (e.g., hookworms [Ancylostoma duodenalis and Necator americanus] and S. stercoralis).

Soil-transmitted helminth infections (roundworm, whipworm, hookworm)

Distribution

The WHO's Preventive Chemotherapy and Transmission Control databank provides data on the distribution of soil-transmitted helminthiases, worldwide.

| Figure 2. Trichuris (whipworm) egg and adult female worm |

|

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, DPDx, Public Health Image Library (PHIL): http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp |

Morbidity

- Most pathology associated with soil-transmitted helminth infection relates to parasite load, which decreases rapidly after a person leaves an endemic area because these nematodes have a relatively short lifespan. People with low parasite loads usually are asymptomatic. With heavier loads, there may be diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal distension or general malaise.1

- Infection with gastrointestinal parasites can cause malabsorption, malnutrition and resultant stunting, and chronic anemia, which in turn may affect a child’s physical and cognitive development.

| Type of morbidity | Sign of morbidity | Parasite |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional impairment | Intestinal bleeding, anaemia |

Ancylostoma duodenale |

| Malabsorption of nutrients | Ascaris lumbricoides | |

| Competition for micronutrients | A. lumbricoides | |

| Impaired growth | A. lumbricoides | |

| Loss of appetite and reduction of food intake | A. lumbricoides | |

| Diarrhea or dysentery | Trichuris trichiura | |

| Cognitive impairment | Reduction in fluency and memory | T. trichiura |

| Conditions requiring surgical intervention | Intestinal and biliary obstructions | A. lumbricoides |

| Rectal prolapse | T. trichiura | |

|

Sources: Adapted from World Health Organization, Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases – First WHO report on neglected tropical diseases, 2010. Geneva: WHO page 138; Montresor A., et al. Helminth control in school age children: A guide for managers of control programmes. Geneva: WHO, 2010. |

||

Diagnosis

At least 2 stool samples collected on different days in preservative should be examined for ova and parasites.2 In one study of foreign adoptees, among the 194 children with any pathogen who had submitted 3 stool samples, the probability of identifying a parasite was 79% when 1 stool specimen was tested, 92% when 2 specimens were tested and 100% for 3 specimens.3 Such testing should not be limited to antigen testing and should include permanent stains and acid fast staining.4,5 The absence of worms in the stool does not rule out some infections (see Strongyloides, below). If you suspect a specific parasite based on history, epidemiology or physical examination findings, it is helpful to indicate the name of the parasite on the requisition. A microbiology laboratory with experience in identifying parasites, such as the Public Health Laboratory, may have access to additional specialized diagnostic tests.

Strongyloides stercoralis

Distribution

An estimated 100 million persons worldwide are chronically infected with S. stercoralis. Prevalence in serosurveys of refugee populations range from 11% to 69%.6 A comprehensive review by the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH) concluded that immigrants from South East Asia and Africa should be screened.7 The CDC website includes information on the life cycle of S. stercoralis.

Morbidity

Most infections with Strongyloides are asymptomatic. Infective (filariform) larvae, acquired by skin contact with contaminated soil, may produce transient pruritic papules at the site of penetration.8 Larvae migrating to the lungs can cause a transient pneumonitis associated with eosinophilia (Loeffler-like syndrome). Unexplained eosinophilia (blood eosinophil count >500/mL) may be the only presenting finding, but eosinophils can be absent later in chronic infection. After ascending the tracheal bronchial tree, larvae are swallowed and then mature into adults within the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms include nonspecific abdominal pain, vomiting and watery diarrhea with mucus. Anorexia and malabsorption can lead to failure to thrive and stunted growth in children. Larval migration from organisms exiting the anus can result in pruritic serpiginous erythematous tracks in the peri-anal area, buttocks, and upper thighs.8,9

Unlike roundworm, whipworm and hookworm, Strongyloides is able to “autoinfect” or replicate and maintain its life cycle inside one person. Subclinical or low-grade infection can persist and cause severe morbidity or death decades after the person leaves an area of endemic infection.10

Autoinfection can produce thousands of adult parasites in the intestine or “hyperinfection syndrome”.8 Hyperinfection may lead to disseminated infection, where larvae migrate via the systemic circulation to other organs, including the brain, liver, heart and skin. Larvae may be found in sputum or spinal fluid as a result.9 Hyperinfection or disseminated disease is characterized by fever, abdominal pain, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates and septicemia or meningitis caused by enteric Gram-negative bacilli.9 Patients who are immunocompromised are at higher risk of dissemination and death. Usually, these are people:

- receiving glucocorticoids for underlying malignancy or autoimmune disease

- receiving biologic response modifiers

- infected with human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1)

- with severe malnutrition.8,9

| Figure 3. A hookworm (left), and a Strongyloides (right) filariform infective stage larvae |

|

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Dr. Mae Melvin: http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp |

Diagnosis

Excretion of larvae in feces is highly variable.8 Three consecutive stool specimens examined microscopically for characteristic larvae (not eggs) result in <60% sensitivity. Sensitivity increases to >90% when 7 specimens are examined.6 Serological tests are more sensitive than stool microscopy and are preferred. The National Reference Centre for Parasitology in Montreal performs serologic testing for Strongyloides.

Who should be screened?

Using serological tests to screen newly arrived refugees of all ages from areas of the world that are highly endemic for strongyloidiasis is recommended by the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health,10 as well as by the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases.

Because complications with hyperinfection syndrome can be life-threatening, serological testing should also be performed for any immigrant from any endemic area before they start immunosuppressive therapy or if they are diagnosed with an immunocompromising condition.

Since eosinophilia (blood eosinophil count >500/mL), may be a sign of strongyloidiasis, serodiagnosis is mandatory for all people from developing countries with unexplained eosinophilia.8

Treatment

Consultation with a paediatric infectious diseases or tropical medicine specialist is recommended before commencing treatment with ivermectin or albendazole.

Ivermectin, the treatment of choice for both chronic (asymptomatic) strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection with disseminated disease,8 is only available through the Health Canada Special Access Program. Treatment with albendazole or thiabendazole is associated with lower cure rates, so is only recommended if there are contraindications to ivermectin. Prolonged or repeated treatments may be necessary in people with hyperinfection and disseminated strongyloidiasis and relapses can occur. With disseminated strongyloidiasis, broad-spectrum antibiotics are indicated for secondary bacterial complications such as sepsis or meningitis. See Table 2 for information on treatment.

The prognosis is excellent in patients who are treated promptly but disseminated infection has fatality rates exceeding 50%.6

Health Canada’s Special Access Programme

Practitioners can obtain drugs that are unavailable for sale in Canada through SAP, Health Canada’s Special Access Programme. The program provides access to therapies for patients with serious medical conditions on an emergency basis. More information on the program, along with application forms, are available on Health Canada’s website.

|

Intestinal parasite |

Suggested therapy for children and adolescents |

|---|---|

|

Roundworms |

|

|

Pinworms |

|

|

Hookworms |

|

|

Strongyloidiasis |

|

|

Whipworm |

|

|

* Not licensed in Canada but available for order through Health Canada’s SAP.8,11,12 |

|

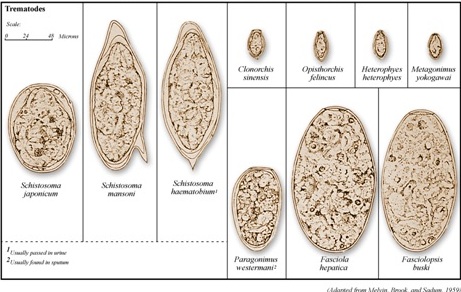

Flukes (trematodes)

Flukes are a group of parasites with a life cycle that requires a specific intermediate fresh water snail host to determine their distribution. Blood flukes infect humans by penetrating skin surfaces, while food-borne flukes infect humans through the ingestion of specific foods. Due to their tissue-invasive character, all trematodes tend to cause eosinophilia.

Schistosomiasis (previously known as Bilharziasis)

Schistosomiasis is an acute and chronic parasitic disease caused by blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma.13 Most human schistosomiasis is caused by S. haematobium, S. mansoni and S. japonicum. Less prevalent species are S. intercalatum and S mekongi. The CDC website has information on the life cycle of schistosomiasis.

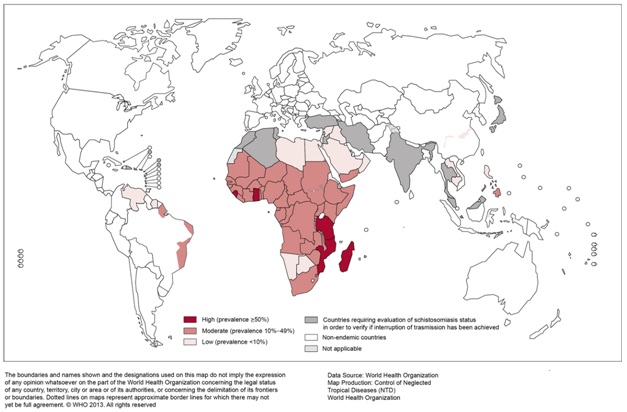

Distribution

Some 700 million people in 78 countries are at risk for schistosomiasis, while 240 million are believed to be infected.14 There are an estimated 200,000 associated deaths annually in sub-Saharan Africa, where all countries except Lesotho are considered endemic for schistosomiasis. S. mansoni and S. haematobium are the most significant trematodes in newly arriving refugees because of their high prevalence rates in sub-Saharan Africa, at 15% to 46%.6

| Figure 4. Geographic distribution of schistosomiasis | |

|

|

| Source: Reproduced, with permission of the publisher, from the World Health Organization’s Global Health Observatory Map Gallery, accessed 16 December 2014) |

Etiology and presentation

Infants may be infected with schistosomiasis when they accompany their mothers to lakes and other open fresh water sources. Lack of hygiene and swimming or fishing in infested lakes makes school-aged children especially vulnerable to high-level infection. Dams, irrigation systems and increased migration to urban areas are increasing transmission to new areas.15

People become infected when larval forms of the parasite, released by freshwater snails, penetrate the skin. There may be a transient pruritic, papular rash. The organisms then enter the bloodstream, migrate through the lungs to the venous plexus that drains the intestines (S. mansoni and S. japonicum) or the bladder (S. haematobium), where the adult worms live for an average of 3 to 5 years16 but potentially for up to 30 years.13 Female worms produce hundreds (S. mansoni and S. hematobium) to thousands (S. japonicum) of eggs per day.13 Some eggs pass out of the body in feces or urine, but others become trapped in body tissues, causing immune reactions and progressive damage to organs.

Acute schistosomiasis (or Katayama disease) is a systemic hypersensitivity reaction that occurs when the female begins to produce eggs. This process can begin 2 to 12 weeks after exposure.16 Fever, malaise, rash, lymphadenopathy, cough, rales, anorexia, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, tender hepatomegaly and mild splenomegaly may occur. Eosinophilia is common. Resolution usually occurs in 2 to 4 weeks, but fatalities also occur.

Most children with intestinal schistosomiasis are asymptomatic.13 Children with higher worm burdens may have anorexia, malaise and abdominal fullness. Protein-losing enteropathy and blood loss can lead to malnutrition and iron deficiency as well as stunted growth and impaired cognitive development.17 Life-threatening complications caused by S. japonicum and S. mansoni are caused by eggs that remain in the venous vasculature and migrate back to the liver, precipitating portal fibrosis or hypertension (i.e., hepatosplenomegaly, ascites and esophageal varices).16 In adolescents and adults, death usually results from gastrointestinal bleeding. Hepatocellular function is usually preserved, such that jaundice and liver enzyme elevations are unusual.9

Urogenital schistosomiasis (S. haematobium) can cause bladder fibrosis. Terminal hematuria occurs as the inflamed bladder contracts during voiding but usually disappears after the age of 12 to 15 years. Recurrent urinary tract infections and nephrotic syndrome have been reported.16 Hydronephrosis, bladder stones, bladder cancer and renal failure are seen more often in adults than in children. Urogenital schistosomiasis is a risk factor for HIV infection, especially in women.18,19

Eggs can embolize:

- To the lungs, leading to cor pulmonale,

- To the spinal cord (S. mansoni or S. haematobium), leading to transverse myelitis, or

- To the brain (especially S. japonicum), precipitating seizures.

Who should be screened?

A reasonable approach is to screen all children, including asymptomatic children, who have returned or emigrated from a schistosomiasis-endemic area, especially when they have had potential exposure to fresh water.9 In children, the pathology is usually primarily inflammatory and reversible with treatment. However, advanced liver fibrosis or severe nephropathy may be irreversible.13

Diagnosis

Schistosomiasis is diagnosed by detecting eggs in stool or urine specimens or antibodies and/or antigens in blood or urine samples.13 Standard stool studies are not as sensitive for schistosomiasis as they are for soil-transmitted helminthes.6 Collecting 3 urine (in areas of S. haematobium) and/or stool specimens (in areas of S. mansoni, S. japonicum) on 3 separate days is recommended.6 Egg excretion in urine is most likely to be positive at the end of voiding between noon and 3:00 p.m. Hematuria may be present.6 Studies using stool microscopy to detect schistosomiasis in African refugee populations have reported prevalences from 0.4% to 7%. Specific serologic tests may be particularly helpful for detecting light infections.20 Studies using serologic enzyme immunoassays have reported significantly higher prevalences, ranging from 2.2% in East African paediatric populations to 64% and 73% in Sudanese and Somali refugees respectively.10 Both the CDC and the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases also support the use of serologic testing to screen for schistosomiasis.

An ultrasound of the urinary tract should be performed in any child infected with S. hematobium.9 Where clinically indicated, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head should be ordered for suspected neuroschistosomiasis.

Treatment

Consultation with a paediatric infectious diseases or tropical medicine specialist is recommended.

Praziquantel, which paralyzes and kills the worms within a few hours, is the recommended treatment. Adverse effects are usually mild (transient nausea or malaise). In heavy infections, treatment may result in transient bloody diarrhea.9,10,16 Praziquantel is effective in >90% of children treated. When treating neuroschistosomiasis, praziquantel should be combined with corticosteroids and (possibly) anticonvulsants, to avoid acute exacerbations after the death of ectopic worms.16

A vaccine is not yet available for clinical use. See Table 3 for information on treatment.

Food-borne flukes (trematodiasis): The most “neglected” of the neglected worms

More than 750 million people (>10% of the world’s population) are at risk for trematodiasis, with 56 million people infected in over 70 countries. Southeast Asia and South America are the most affected areas.20,21

|

Figure 5. Trematode eggs found in stool specimens of man |

|

|

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Dr. Mae Melvin: http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp |

| Intestinal parasite | Suggested therapy for children and adolescents |

|---|---|

|

Flukes |

|

|

Sheep liver fluke |

|

|

Lung fluke |

|

|

Schistosomiasis (Bilharziasis) |

|

|

* Not licensed in Canada but available for order through Health Canada’s SAP.8,11,12 |

|

The most important food-borne “flukes” (or trematodes) infecting humans are the biliary liver flukes (Opisthorchis viverrini, Clonorchis and Fasciola hepatica), intestinal flukes (Fasciolopsis buskii) and lung flukes (Paragonimus spp.). These organisms tend to chronically infect specific populations, depending on dietary consumption of certain types of raw fish (Clonorchis, Opisthorchis), crustaceans (Paragonimus) or aquatic plants (F. hepatica) contaminated with the infective stages. The biliary liver flukes, particularly Opisthorchis spp. and C. sinensis, are associated with development of cholangiocarcinoma.

Tapeworms (cestodes)

Information related to beef (Taenia saginata) and pork (Taenia solium) tapeworm infections is provided elsewhere on this website. See Cysticercosis and Taeniasis.

When humans eat undercooked fish with encysted larvae, they become infected with the adult form of Diphyllobothrium latum, the fish tapeworm. See Table 4 for information on treatment.

| Intestinal parasite | Suggested therapy for children and adolescents |

|---|---|

|

Tapeworms |

|

| H. nana (dwarf tapeworm) |

|

|

Cysticercosis – See also Cysticercosis and Taeniasis |

|

|

Hydatid cyst (Echinococcus spp) |

|

|

*See reference 22. Niclosamide (manufactured by Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Finland) is not licensed in Canada. Health Canada’s Special Access Program assesses each request. |

|

Protozoa/Coccidia

Diarrheal disease lasting longer than 14 days after arrival from the tropics is likely to be caused by protozoan parasite infection.

Giardiasis, presenting with watery diarrhea, steatorrhea and malabsorption, is a common infection in the paediatric age group.23

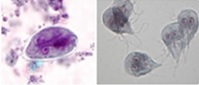

|

Figure 6. Giardia cyst and trophozoites

|

|

|

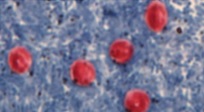

Figure 7. Cryptosporidium oocysts

|

|

|

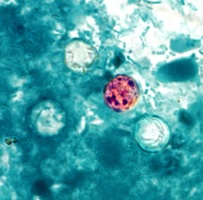

Figure 8. Cyclospora oocyst

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Melanie Moser: http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/home.asp |

|

|

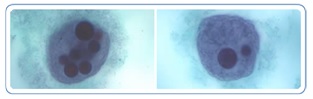

Figure 9. E. histolytica trophozoites with ingested red blood cells

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, DPDx. Parasites - Amebiasis (also known as E. histolytica infection). |

|

Cryptosporidiosis and cyclosporiosis present with watery diarrhea that may be prolonged in patients with HIV/AIDS.24,25

Amebiasis: An estimated 50 million illnesses and 100,000 deaths due to Entamoeba histolytica occur around the world every year, predominantly in Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Central and South America.9 There are two morphologically similar but genetically distinct species: E. histolytica is an invasive, disease-causing parasite; E. dispar is a noninvasive, commensal parasite. E. histolytica may present with asymptomatic intestinal infection or with bloody diarrhea (dysentery) which can be chronic and mimic symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease. Extraintestinal disease develops in a small proportion of patients, usually in the liver. From the liver, E. histolytica can spread to the pleural space, lungs and pericardium, as well as to the brain and other areas of the body. The formation of liver, thoracic, pericardial or brain abscesses can, if ruptured, lead to death.26 The CDC website includes information on the life cycle of Entamoeba histolytica.

Diagnosis

A presumptive diagnosis of intestinal tract infection depends on identifying trophozoites (active protozoa) or cysts in stool specimens. Trophozoites containing ingested red blood cells are more likely to be E. histolytica than E. dispar.26 Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits are used for routine serodiagnosis of amebiasis. The EIA detects antibody specific for E. histolytica in approximately 95% of patients with extraintestinal amebiasis, 70% of patients with active intestinal tract infection and 10% of asymptomatic people who are passing cysts. Ultrasound, CT and MRI can identify liver abscesses and other extraintestinal sites of infection.26

| Intestinal parasite | Suggested therapy for children and adolescents |

|---|---|

|

Protozoan amebiasis |

For asymptomatic infection:

If colitis or liver abscess is present: |

|

Cryptosporidiosis |

Repeated treatment courses may be needed |

|

Cyclosporiasis |

Trimethoprim (TMP)/sulfamethoxazole(SMX): TMP 10 mg/kgSMX 50 mg/kg/day) PO divided bid x 7-10 days |

|

Giardiasis |

|

|

Cystoisosporiasis |

Trimethoprim (TMP)/sulfamethoxazole (SMX): TMP 10 mg/kg/day and SMX 50 mg/kg/day) PO divided bid x 10 days |

|

* Not licensed in Canada but available for order through Health Canada’s SAP.8,11,12 |

|

Treatment options are limited for many parasitic diseases. Consulting a paediatric infectious diseases or tropical medicine specialist is always recommended for patients diagnosed with a gastrointestinal parasitic infection requiring antiparasitic drugs through Health Canada’s Special Access Program. They can advise and caution regarding the use of specific drugs in different age groups and in individuals who may be coinfected with more than one parasitic infection. Adverse events are also associated with specific drugs, particularly when the parasitic infection involves the central nervous system.

Drug-specific cautions include, for example:

- The safety of albendazole use in children

- The safety of praziquantel use in children <4 years of age, which remains to be established

- The safety of ivermectin in young children weighing <15 kg, which remains to be established.

Conclusion

A companion document, Gastrointestinal parasites – an overview, provides additional information on the disease burden and geographical distribution of gastrointestinal parasitic infections in immigrant and refugee children. Appropriate screening and the early diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal pathogenic parasites in young newcomers to Canada can help to reduce morbidity and prevent complications.

Selected resources

- Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases. Diagnosis, management and prevention of infections in recently arrived refugees. Sydney, NSW: Dreamweaver, 2009.

- Banerji A, Li P, Navaranjan D. The health and nutritional status of new refugee, immigrant, and uninsured children in Toronto, Canada. CERIS, The Ontario Metropolis Centre, Research Summary October 2012.

- Boggild AK, Yohanna S, Keystone JS, Kain KC. Prospective analysis of parasitic infections in Canadian travelers and immigrants. J Travel Med 2006;13(3):138-44.

- Bradley JS, Nelson Jd, Kimberlin DW, et al. 2014 Nelson’s Pediatric Antimicrobial Therapy, 20th edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.)

- Daly R, Chiodini PL. Laboratory investigations and diagnosis of tropical diseases in travelers. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2012;26(3): 803-18.

- Furst T, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Global burden of human foodborne trematodiasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12(3):210-21.

- Knopp S, Steinmann, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Nematode infections: Soil-transmitted helminths and trichinella. Inf Dis Clin North Am 2012;26(2):341-58.

- Manganelli L, Berrilli F, Di Cave D, et al. Intestinal parasite infections in immigrant children in the city of Rome, related risk factors and possible impact on nutritional status. Parasit Vectors 2012,5:265.

- Muennig P, Pallin D, Sell RL, et al. The cost effectiveness of strategies for the treatment of intestinal parasites in immigrants. N Engl J Med 1999;340(10):773-9.

- Pickering, LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, eds. Red Book, 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 29th edition. Elk Grove, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics: 194-5, 239-40, 333-5, 411-3, 453-4, 532-3, 537, 643-5, 689-90, 731-2, 848-68.

- Sripa B. Global burden of foodborne trematodiasis. Lancet Infecti Dis 2012;12(3):171-2.

- World Health Organization

- Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases – First WHO report, 2010

- Action against worms

- Preventive chemotherapy in human helminthiasis: Coordinated use of anthelminthic drugs in control interventions; a manual for health professionals and programme managers. 2006

- Zouré HG, Wanji S, Noma M, et al. The geographic distribution of Loa loa in Africa: Results of large-scale implementation of the Rapid Assessment Procedure for Loiasis (RAPLOA). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011;5(6):e1210.

References

- Soil-transmitted helminthes. Fact sheet 366, June 2013.

- Minnesota Department of Health. Minnesota refugee health provider guide 2013: Parasitic infections.

- Staat MA, Rice M, Donauer S, et al. Intestinal parasite screening in internationally adopted children: Importance of multiple stool specimens. Pediatrics 2011;128(3):e613-22.

- Public Health Agency of Canada, CATMAT. Statement on persistent diarrhea in the returned traveller. CCDR, February 15, 2006;32(ACS-1).

- Swanson SJ, Phares CR, Mamo B, et al. Albendazole therapy and enteric parasites in United States-bound refugees. N Engl J Med 2012;366(16):1498-507.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine). Intestinal parasite guidelines for domestic medical examination for newly arrived refugees: Presumptive treatment and screening for strongyloidiasis, schistosomiasis and infections caused by soil-transmitted helminths for refugees, November 6, 2013.

- Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. Appendix 8: Khan K, Heidebrecht C, Sears J, et al; Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH). Intestinal parasites – Strongyloides and Schistosoma: Evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees: www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.090313/-/DC1.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Strongyloidiasis (S. stercoralis). In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, eds. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 29th edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: AAP, 2012:689-90.

- Cherry JD, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, et al, eds. Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 7th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2014.

- Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. Chapter 10: Intestinal parasites: Strongyloides and Schistosoma. CMAJ 2011; 283(12):E865-8.

- Drugs for parasitic infections. Treatment guidelines from the Medical Letter, Vol.11 (Suppl), 2013:e1-31.

- Bradley JS, Nelson JD, Kimberlin DW, eds. 2014 Nelson’s Pediatric Antimicrobial Therapy, 20th edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2014.

- World Health Organization. Schistosomiasis. Fact sheet 115, February 2014.

- World Health Organization. World Health Day 2014: Preventing vector-borne diseases.

- World Health Organization. 10 facts about schistosomiasis. March 2014.

- Gryseels B. Schistosomiasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2012;26 (2):383-97.

- King CH, Dangerfield-Cha M. The unacknowledged impact of chronic schistosomiasis. Chronic Illn 2008;4(1):65-9.

- World Health Organization. Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases – Update 2011.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Schistosomiasis. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, eds. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 29th edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: AAP, 2012:643-45.

- World Health Organization. Foodborne trematodiases. Fact sheet 368, April 2014.

- World Health Organization. Foodborne trematode infections.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Other tapeworm infections. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, eds. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 29th edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: AAP, 2012:705-6.

- Wright SG. Protozoan infections of the gastrointestinal tract. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2012;26(2):323-40.

- Harhay MO, Horton J, Olliaro PL. Epidemiology and control of human gastrointestinal parasites in children. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2010;8(2):219-34.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Cryptosporidiosis and Cyclosporiasis. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, eds. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 29th edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: AAP, 2012:296-300.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Amebiasis. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, eds. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 29th edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: AAP, 2012:222-5.

Reviewer(s)

Heather Onyett, MD

Last updated: May, 2015