Malaria

Key points

- Malaria is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, especially in children under 5 years old in sub-Saharan Africa.

- In 2018, malaria caused approximately 405,000 deaths worldwide, with an estimated 228 million cases of the disease.

- Routine screening of asymptomatic immigrants and refugees to Canada is not recommended.

- Malaria should be suspected in a person with fever who has lived in or travelled through an area where the disease is endemic, especially within the previous 3 months. Symptoms of malaria can be non-specific (fever, headache, malaise) and mimic a severe flu-like illness.

- The presence of fever alone in a person from an endemic area is reason enough to investigate for malaria.

- Malaria is a medical emergency. Early diagnosis is essential. Delays in diagnosis and treatment may lead to death.

- Diagnosis of malaria is made using thick and thin malaria blood smears and/or rapid diagnostic tests.

- Preventing malaria in children and their families who visit friends and relatives in endemic areas is important. Using appropriate anti-malarial drugs, insect repellants, and insecticide-treated bed nets are the best protective measures.

Epidemiology and risk factors

Malaria is a febrile illness associated with high morbidity and mortality rates in children in the tropics, especially sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and, less frequently, some parts of Central and South America.

In 2018, nearly half the world’s population were at risk of malaria. During that year there were 228 million cases and about 405,000 deaths from the disease. Of the latter, 67% were in children under 5 years of age and 94% occurred in the African region.1

It is not known how many young newcomers to Canada are affected by malaria. Children ≤ 19 years may be over-represented, comprising 23% of cases reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada (1998-2008) but only 8.7% of international travellers (2011). 2 Of the 195 cases of severe or complicated malaria reported to the Canadian Malaria Network between 2001 and 2012, 21.1% of cases occurred in children, of whom the majority were foreign-born.2

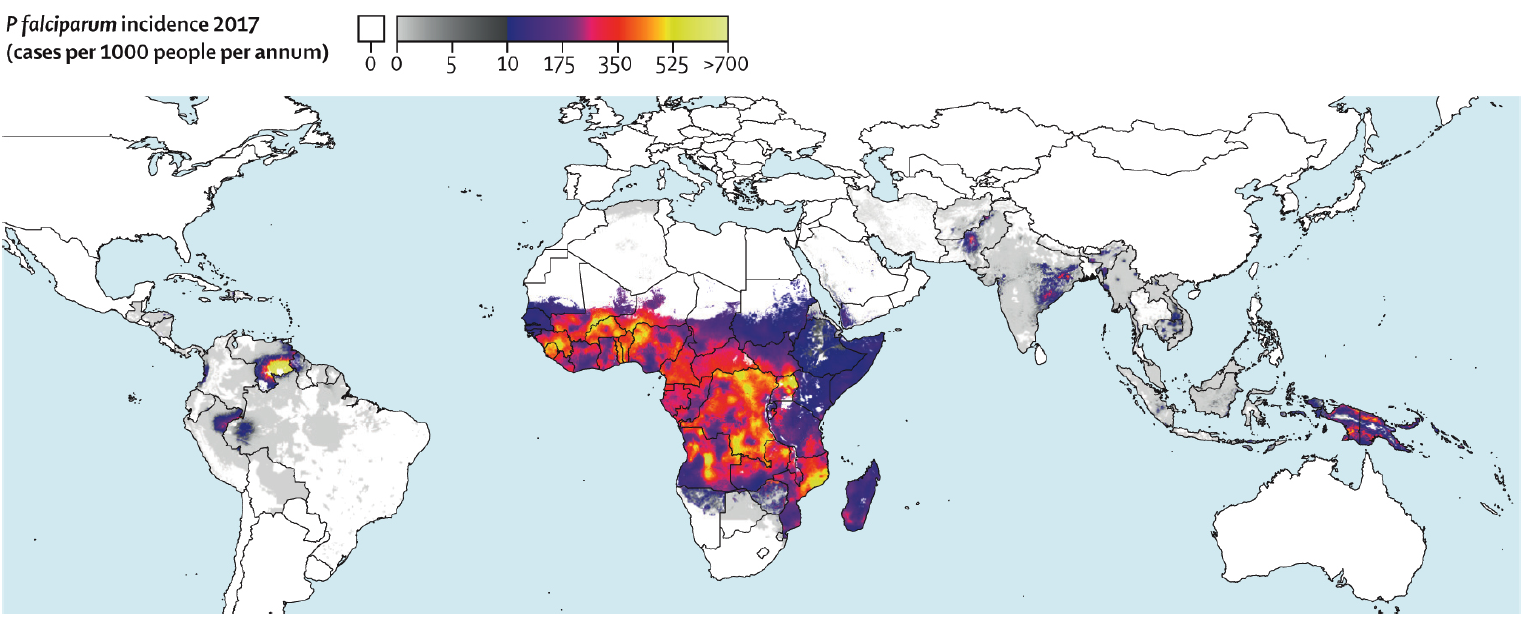

Consider a diagnosis of malaria for any patient with febrile illness occurring after they have lived in or travelled through a malaria-endemic area (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Global Incidence of P falciparum* from Weiss et al.3

Figure 1: Global Incidence of P falciparum* from Weiss et al.3

Etiology

Seven species of the malaria parasite cause disease in humans: Plasmodium falciparum (the most virulent), P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale curtisi, P. ovale wallikeri, P. knowlesi and P. simium. Transmission occurs primarily through bites from infected female Anopheles mosquitoes and, less frequently, from blood transfusions, through use of contaminated needles and syringes, and from mother to child via the placenta (the newborn then presents with congenital malaria).

Incubation periods vary considerably, which for the 5 most important human species include:

- P. falciparum: Between 2 weeks and 3 months after last exposure; the majority present within 1 month after last exposure.

- P. vivax, P. ovale or P. malariae: Up to a year or more after exposure. Relapses due to P. vivax and P. ovale occasionally occur more than 1 year after initial infection.

- P. knowlesi: The incubation period of P. knowlesi is unknown.

The presence of fever alone in a person from an endemic area is reason enough to investigate for malaria.

Clinical clues

Malaria is characterized by the sudden onset of chills, rigors and fever to as high as 41°C. Patients may also experience nausea, diarrhea, arthralgias, headache and delirium. Associated signs include postural hypotension, anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, abdominal pain and back pain.

Paroxysms of fever and chills, often followed by sweats, classically recur at 48-hour intervals with P. vivax, P. ovale and P. falciparum, and at 72-hour intervals with P. malariae. However, it may be a number of days in the absence of antimalarial treatment before this pattern becomes apparent with P. falciparum. Malaria may mimic a severe flu-like illness.

Severe or complicated P. falciparum malaria

Severe or complicated malaria is defined as acute malaria with high levels of parasitemia (>2%) and/or evidence of end-organ dysfunction. Complications of malaria are summarized below.

Mortality may be greater than 20% to 30% in severe malaria due to P. falciparum. Of the three classic clinical syndromes associated with malaria in children (respiratory distress, cerebral malaria, and severe anemia), respiratory distress is associated with the highest mortality.4

In a patient with P. falciparum asexual parasitemia and no other obvious cause of symptoms, the presence of one or more of the clinical or laboratory features below classifies the patient as suffering from severe malaria.

|

Clinical manifestation |

|

Laboratory test |

|---|---|---|

|

Prostration/impaired consciousness |

|

Severe anemia (hematocrit <15%; Hb ≤ 50 g/L) |

|

Respiratory distress |

|

Hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 2.2 mmol/L) |

|

Multiple convulsions |

|

Acidosis (arterial pH <7.25 or bicarbonate < 15 mmol/L) |

|

Circulatory collapse |

|

Renal impairment (creatinine > 265 µmol/L) |

|

Pulmonary edema (radiological) |

|

Hyperlactatemia |

|

Abnormal bleeding |

|

Hyperparasitemia: |

|

Jaundice |

|

≥2% for children < 5 yrs* |

|

Hemoglobinuria |

|

≥5% for non-immune# adults and children ≥ 5yrs ≥10% for semi-immune# adults and children ≥ 5yrs |

|

*Some young children with parasitemia >2-5% who have had several previous malaria infections, meet no other criteria for severe malaria, and are being observed in hospital may be candidates for atovaquone-proguanil treatment if they can be monitored closely and parenteral therapy is available should their condition change. # Non-immune individuals would include those born in non-endemic countries or low-transmission settings, such as travellers. In addition, those who have previously lived in endemic settings would be considered to have lost their immunity after a period of time away from malaria exposure (≥ 6-12 months out of the endemic setting). Semi-immune individuals would be evidenced by birth and long-term residence in an endemic country and prior episodes of malaria. Adapted from: Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria, 2015, World Health Organization. Source: Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT). 2019 Canadian recommendations for the prevention and treatment of malaria among international travellers.2 |

||

Note that prostration and respiratory distress are common features in children, whereas pulmonary edema and renal failure are seen more commonly in adults.

Non-falciparum malaria

P. vivax and (rarely) P. ovale can also cause severe malaria, with respiratory distress being the usual key manifestation. Because the life cycles of P. vivax and P. ovale include a latent liver stage (hypnozoite), these species can be associated with relapsing episodes weeks to years after the initial infection. The section on Antimalarial therapy provides information on treatment to prevent relapses.

P. malariae occurs infrequently in Canada, often as a co-infecting species, but is associated with nephrotic syndrome in chronic cases in endemic countries. P. knowlesi is a newly emerging pathogen that presents with a similar clinical picture to P. falciparum but which resembles P. malariae on microscopy.

There may also be co-infection: for example, with both P. falciparum and P. vivax.

The most important factors that determine patient survival are early diagnosis and appropriate therapy. The majority of infections and deaths due to malaria are preventable.2

Diagnosis

When malaria is in the differential diagnosis, laboratory diagnosis must be done promptly and accurately, especially if there is a possibility of P. falciparum infection based on the travel history.

Malaria is a medical emergency. If prompt diagnostic services are not available, consult a specialist in infectious diseases or tropical medicine for recommendations on acute management.

Diagnosis using blood smears

Malaria is diagnosed using thick and thin Giemsa-stained blood smears in most centres:

- The thick smear allows concentration of the blood, so that parasites present in small numbers might be more easily identified.

- The thin smear permits species identification and allows quantification of parasitemia.

- A single blood smear may be falsely negative for the malaria parasite. Due to the cyclic nature of malaria parasitemia, if symptoms persist, blood films (and/or rapid diagnostic tests) should be repeated every 12 to 24 hours, at least two more times, before malaria is ruled out as a cause of fever.2

Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs)

Various test kits are available to detect antigens derived from lysed, malaria-infected red blood cells. RDTs use small blood volumes from either fingerstick or anticoagulated blood, provide results in 5 to 20 minutes, and have high sensitivity. These RDTs are a useful adjunctive, rapid or alternative test to microscopy, particularly when reliable microscopic diagnosis is not available. Because the usual lower limit of identification is ~100 parasites of P. falciparum per microlitre, the blood smear may be positive despite a negative RDT. Most kits only distinguish falciparum from non-falciparum species, so blood smears are still needed for speciation in non-P. falciparum cases as well as to quantify parasitemia.

Other diagnostic tests such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are available in some centres, and are highly sensitive.

Other tests

Other tests include:

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential and platelet count. The most common early abnormality is thrombocytopenia. Malaria causes hemolysis and there may be an associated anemia that is not necessarily seen at presentation. During rigors the white cell count may be elevated; at other times, it is usually normal or low.

- Urea and creatinine may be elevated because of dehydration and/or renal impairment.

- Liver function tests, including bilirubin, may be elevated because of hemolysis or organ dysfunction.

- Blood glucose may be low because children with malaria are at high risk of hypoglycemia, especially if they are receiving treatment with quinine.

- Blood cultures should be drawn. Particularly in children, the differential diagnosis may include sepsis, bacterial pneumonia, or meningitis. Although enteric bacteria (notably Salmonella spp.) have predominated in most trials, a variety of bacteria have been cultured from the blood of patients who have also been diagnosed with malaria.

Treatment

As a general rule, all children with symptomatic P. falciparum malaria should be admitted to hospital. Patients with other forms of malaria should also be considered for admission, particularly if they are not able to tolerate oral medications. Because malaria is not transmitted from person to person, isolation is not required.

- If the attending physician does not have experience treating individuals with malaria, the physician should immediately consult a specialist in infectious diseases or tropical medicine.

- If there is no local expertise in the management of a patient with malaria, the Public Health Agency of Canada provides a list of physicians across Canada involved in the Canadian Malaria Network who can also provide advice on case management.

Antimalarial medications

For further information on specific antimalarial treatment recommendations, including drugs, dosages and contraindications, please refer to:

- Canadian Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Malaria Among International Travellers. Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019. www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/catmat/canadian-recommendations-prevention-treatment-malaria.html

- Malaria Treatment (United States), 2020. U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) www.cdc.gov/malaria/diagnosis_treatment/treatment.html

- Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria, 3rd Edition, 2015. World Health Organization. www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241549127/en/

Antimalarial therapy

Medication selection varies with the species of malaria, severity of illness, region of acquisition (due to resistance patterns) and host factors.

For uncomplicated P. falciparum, isolates are resistant to chloroquine in most regions of the world except northwest of the Panama Canal, the Caribbean islands and select areas of Asia. Refer to the CATMAT appendix for geographic information on drug-resistant malaria. Currently, oral artemisinin combination options are not licensed or available in Canada. Therefore, atovaquone/proguanil or oral quinine plus an additional drug are generally used.

Severe malaria, although not common in Canada, has been rising in recent years. A total of 367 cases required intravenous therapy (artesunate or quinine) from the Canadian Malaria Network between 2014 and 2017, of whom 103 (28%) were children. The most common reason for travel was to visit friends and relatives. Notably, children accounted for 22% of all VFRs and 71% of recent immigrant cases.6 In the case of severe or complicated P. falciparum disease, with a mortality rate of 20% or higher, children should be urgently transferred to a centre with experience in managing this condition and preferably to one of the Canadian Malaria Network sites stocking intravenous (IV) artesunate under the Special Access Programme. The specialist in infectious diseases or tropical medicine may recommend initial oral or IV medication (if locally available) to be started before transfer. Read more about medical access to artesunate or quinine through the Canadian Malaria Network.

P. vivax resistance patterns vary. In most cases chloroquine is effective, but there are regions where resistance has emerged requiring the use of other antimalarials. Practitioners are advised to confer with a consultant in paediatric infectious diseases or tropical medicine to decide therapy on a case-by-case basis. P. ovale and P. malariae are effectively treated with chloroquine regardless of region of acquisition. P. knowlesi is also chloroquine-sensitive. However, when there is severe disease, P. knowlesi should be managed with IV therapy, as for severe P. falciparum.

In malaria due to P. vivax or P. ovale, after treatment of acute illness, patients who do not have the inherited sex-linked deficiency of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) should be given a 2-week course of primaquine to eradicate the liver hypnozoites and prevent relapses of acute malaria. Blood testing for G6PD deficiency is important before prescribing primaquine: individuals who have this deficiency may develop hemolysis if they receive primaquine. The prevalence of G6PD deficiency varies, but it can be as high as 30% in some genetic backgrounds. If a breastfeeding mother is diagnosed with P. vivax or P. ovale malaria, G6PD testing should be done in both the mother and breastfeeding child to determine whether primaquine is contraindicated.

If a patient with P. vivax or P. ovale is diagnosed with G6PD deficiency or has a relapsing course, practitioners should consult with a specialist in infectious diseases or tropical medicine.

Supportive therapy may include:

- Acetaminophen for fever

- Glucose to prevent or treat hypoglycemia

- Fluids to prevent or treat dehydration

- Blood transfusion for severe anemia

- Anticonvulsants for seizures

- Exchange transfusion, which may be lifesaving if the patient has complicated P. falciparum or hyperparasitemia

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics in severe malaria for possible concomitant bacteremia

Importance of health education and awareness

Delays in effective diagnosis and treatment may occur in immigrants and refugees new to Canada for a number of reasons, including:

- Easy access to antimalarial medications in their country of origin.

- The use of traditional remedies or of antimalarial drugs purchased abroad that may be ineffective, substandard or counterfeit.

- Difficulties accessing the Canadian health care system.

- Lack of money to pay for antimalarial drugs.

- Frustration with how complicated it often is to be assessed and treated for malaria in Canada vs. the patient’s country of origin, leading to poor compliance.

Barriers to the rapid diagnosis and treatment of malaria in Canada include:

- A lack of awareness among health care providers concerning the occurrence, severity, appropriate diagnosis and effective treatment of this disease.

- Reduced availability of, or slow turnaround time for malarial diagnostics in some areas.

- Unavailability of oral artemisinin medications in Canada.

Health professionals need to be more aware of malaria in the differential diagnosis of a child or adolescent who has lived in or travelled through an area where the disease is endemic—especially within the previous 3 months. Raising awareness will help to prevent unnecessary morbidity and mortality in high-risk immigrants and refugees new to Canada.

Prevention

Preventing malaria in children and families who visit friends and relatives in endemic areas is important. Protective measures include prophylaxis with appropriate antimalarial drugs, purchased in Canada, and using insect repellants and insecticide-treated bed nets. Preventing malaria in travellers is discussed in the Travel-Related Illnesses module.

Developing a malaria vaccine

There is no licensed vaccine to prevent malaria at this time. The long-term goals for such a vaccine are to protect against clinical malaria and reduce transmission.

A Phase 3 trial of a circumsporozoite vaccine called RTS,S/AS01 (RTS,S) was conducted from 2009 to 2014 in seven African countries, enrolling ~15 500 infants and young children. RTS,S reduced malaria episodes by 39%, and severe malaria by 31.5%.3

Having demonstrated modest efficacy in this large RCT, the WHO coordinated malaria vaccine implementation programme (MVIP) is currently rolling out a large-scale pilot vaccination program in three countries (Ghana, Malawi and Kenya).

Selected resources

- Canadian Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Malaria Among International Travellers - CATMAT. Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019. www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/catmat/canadian-recommendations-prevention-treatment-malaria.html

- Malaria and Travellers for U.S. Residents, 2020.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) www.cdc.gov/malaria/travelers/index.html

- Malaria. World Health Organization. www.who.int/malaria/en/

- Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2011;183(12):E824-925. See Appendix 9: Malaria: Evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. www.cmaj.ca/content/suppl/2010/06/07/cmaj.090313.DC1/imm-malaria-9-at.pdf

References

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report, 2019. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2019. https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2019/en/

- Public Health Agency of Canada. 2019 Canadian Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Malaria Among International Travellers. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/catmat/canadian-recommendations-prevention-treatment-malaria.html

- Weiss DJ, Lucas TCD, Nguyen M, et al. Mapping the global prevalence, incidence, and mortality of Plasmodium falciparum, 2000-17: a spatial and temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2019;394(10195):322-331. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31097-9

- Marsh K, Forster D, Waruiru C, et al. Indicators of life-threatening malaria in African children. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(21):1399-1404. doi:10.1056/NEJM199505253322102

- RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership* Efficacy and safety of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine with or without a booster dose in infants and children in Africa: final results of a phase 3, individually randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386: 31-45

-

McCarthy A, Carson S, Ampaw P, Sarfo S, Geduld J. Severe Malaria in Canada 2014-2017: Report from the Canadian Malaria Network. Int J Infect Dis 2019;79(s1):15. doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2018.11.054

Reviewer(s)

- Heather Onyett, MD

- Michael Hawkes, MD

- Susan Kuhn, MD

Last updated: February, 2023