Oral Health Screening

Key points

- Oral health and dental care are unmet needs of young newcomers to Canada.

- Refugee children may have never received oral health care or been exposed to preventive measures (e.g., a toothbrush, fluoridated toothpaste or water).

- Dental caries in newcomer children can lead to complications: pain, problems with feeding, growth and learning, and damage to permanent teeth.

Oral health is a basic component of children’s health and a particular concern in young newcomers to Canada. Newcomer status is itself a risk factor for early childhood caries (ECC), and young newcomers may not have received dental care before their arrival or learned about oral hygiene in their country of origin.

Complications of early childhood caries:

- Pain

- Difficulty chewing, which can lead to poor feeding and slow weight gain

- Difficulty speaking

- Oral infections

- Loss of sleep, difficulty concentrating and interrupted learning

- Decay and loss of teeth

- Damage to permanent teeth

- Increased risk of caries development

- Increased risk of chronic inflammation and abscess formation

Because newcomers to Canada are more likely to first seek primary health care before dental care, paediatricians, physicians and other health care providers play an important role in screening and referral for dental care.3

Epidemiology

Many Canadian children have poor oral health: Nearly 60% of 6 to 19 year-olds have (or have had) a cavity.4 (Note: More current data are being collected through the Canadian Oral Health Survey.) However, the burden of illness disproportionately affects young newcomers, both in terms of oral health status and use of dental services.

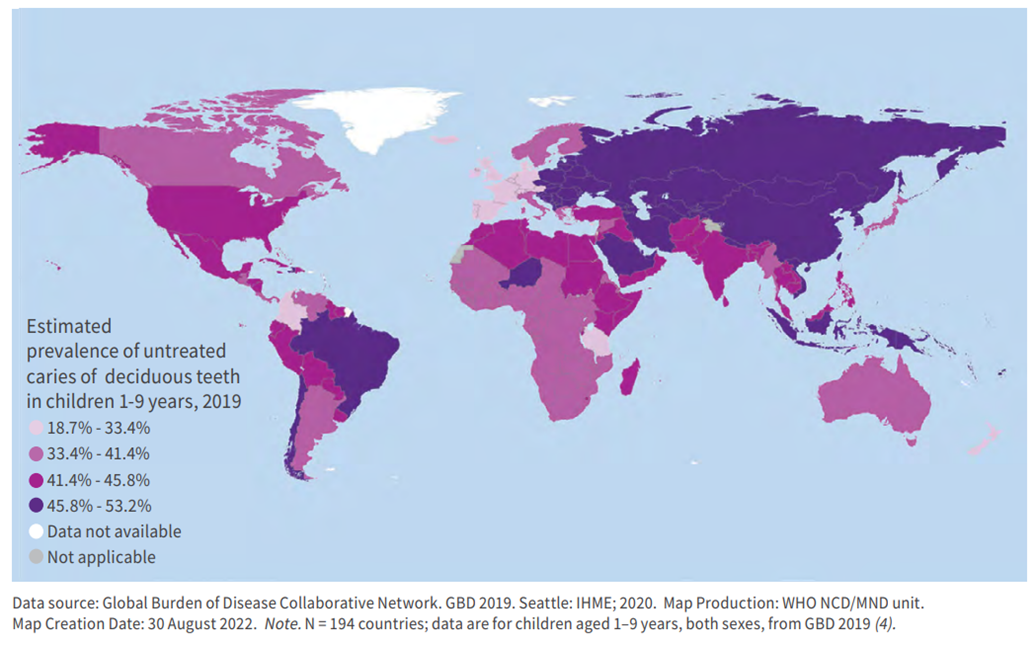

According to the World Health Organization, untreated caries in deciduous teeth is the single most common chronic childhood disease worldwide, and children and youth from minority and/or other socially marginalized groups generally carry a higher burden of oral diseases (see Figure 1).2

| Figure 1: Estimated prevalence of untreated caries of deciduous teeth in children 1-9 years worldwide, 2019 |

|

| Source: Global oral health status report: towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. |

Risk factors

Among the risk factors for early childhood caries are:

- New immigrant status

- Lower income or parental education level

- Lack of a family dentist or of access to dental insurance or coverage

- Breastfeeding at frequent intervals

- Frequent snacking during the day

- A previous history of caries, plaques or demineralization

- Little or no exposure to fluoride

Screening and intervention

Some young newcomers, especially refugees, may have never practiced oral health care (e.g., toothbrushing, fluoridated toothpaste or water) or seen a dental professional before arriving in Canada.

The Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH) has noted that, because physicians are often the first point of contact in the health care system for newcomers, they can play a key role in ensuring oral health through screening and referral.3 CCIHR recommendations are summarized in Table 1.

|

Screen for early signs of caries or obvious cavities and pain |

|

| Refer patients |

|

|

Application of fluoride varnish (by trained provider) |

|

| Recommend teeth brushing |

|

| Screen early feeding and later eating practices |

|

|

Sources: McNally M, Matthews D, Pottie K, for the CCIRH. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. Appendix 16: Dental disease; Evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2011;183(12):E824-925 |

|

Figure 2. White spot lesions

Source: Travis Nelson, DDS, MSD, MPH. Department of Pediatric Dentistry University of Washington.

Figure 3. Mild dental disease

Source: Travis Nelson, DDS, MSD, MPH. Department of Pediatric Dentistry University of Washington.

Figure 4. Moderate dental disease

Source: Travis Nelson, DDS, MSD, MPH. Department of Pediatric Dentistry University of Washington.

Figure 5. Severe dental disease

Source: Travis Nelson, DDS, MSD, MPH. Department of Pediatric Dentistry University of Washington.

Guidance for families

All health providers can encourage and reinforce good oral health practices with newcomer families they see, by sharing these messages:

- Don’t put your baby or toddler to bed with a bottle or sippy cup–at night or at naptime.

- Minimize sugary foods and liquids (including juice and milk). A child doesn’t need to carry a bottle around between feedings.

- Teach children to drink from an open cup near first birthday.

- Never ‘sweeten’ a child’s a pacifier (soother) by dipping it in sugar or honey

- Don’t clean your child’s soother (or anything else they put in their mouth) by putting it in your own mouth: this can pass bacteria or viruses from mother to child.

Other resources:

Dental care for your infant and toddler, HealthLinkBC (available in 8 languages)

Oral health for children (Government of Canada)

Access to care

Dental care is not covered under the Canada Health Act, and lack of insurance coverage can be a barrier to accessing dental care for newcomer families.5,6 One study found that lack of dental care and insurance were the strongest predictors of caries in children younger than 7 years of age.5

Government funding for dental services for which young newcomers to Canada may be eligible is summarized below. Publicly funded dental services tend to have a lower reimbursement scale than private coverage. Discrepancies between public and private reimbursement rates can lead to public patients not being accepted as readily by dentists.7

The Canadian Dental Care Plan pays a portion of the cost of some oral health care services for eligible Canadian residents. Fact sheets on the Canadian Dental Care Plan in multiple languages are available on the Government of Canada’s website.

Federal dental coverage: The Interim Federal Health Program

Refugees and refugee claimants may be eligible for limited dental services under the Interim Federal Health Program. Program details can be found in the Health Insurance for Immigrant and Refugee Families section of this resource and on the Government of Canada website.

Provincial/territorial dental programs

Young newcomers to Canada may be eligible for dental funding assistance through a number of provincial or territorial programs as (see links in Table 2). Many of these programs depend on the child having provincial/territorial health coverage, which may not include all newcomers, and refugee claimants in particular.

| Program | Eligibility | Services covered |

|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | ||

| Healthy Kids | Children and youth 0 –19 yrs from low-income families in receipt of premium assistance through Medical Services Plan |

|

|

Dental Benefits Program for Children and Youth in Foster Care |

Children and youth in foster care covered up to $700/year |

|

| Alberta | ||

| Alberta Child Health Benefit | Children and youth zero – 18 years of age from low-income families | Basic coverage: dental exams, cleaning, X-rays, fillings and extractions |

| Family Support for Children with Disabilities | Children and youth zero – 18 years of age with a disability |

|

| Foster Care | Children and youth zero – 18 years of age in foster care | Basic coverage: dental exams, cleaning, X-rays, fillings and extractions |

| Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) | Children of parents with a disability who are unable to work | Basic coverage: dental exams, cleaning, X-rays, fillings and extractions |

| Saskatchewan | ||

| Family Health Benefits | Children zero – 18 years from low-income families |

Basic coverage |

| Supplementary Health Program | Foster children |

Diagnostic, preventive, restorative, oral surgery |

|

Public Health Services Dental Clinic (Saskatoon Health Region) |

Children zero – 16 years who have limited or no dental coverage |

Preventive and treatment services |

| Manitoba | ||

| Health Services Dental Program | Children <18 years of age who have a disability or are wards of the state covered up to $500/year | Basic diagnostic, preventive, restorative, endodontic, periodontal, prosthodontic, oral surgery services |

| At-risk children in the Winnipeg region | Preventive and basic treatment services | |

| Healthy Smile Happy Child intersectoral partnership |

At-risk infants and preschool children and their families |

Oral health promotion using community development approaches |

|

Children <36 months of age |

Early dental screenings |

|

| Ontario | ||

| Healthy Smiles |

Children 17 years and under from low-income households; and children receiving benefits through |

Preventive and basic treatment services |

| Quebec | ||

| Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec: Children’s Dental Care Program |

All children <10 years of age |

|

|

Children from low-income families |

|

|

| New Brunswick | ||

| Healthy Smiles, Clear Vision | Children <18 years of age from low-income families |

|

| Nova Scotia | ||

| MSI Children’s Oral Health Program |

Children <14 yrs of age

|

|

| Mentally Challenged Program |

|

|

| Prince Edward Island | ||

|

Diagnostic and basic treatment services |

|

| Children’s Dental Care Program (Prevention) | All school-aged children 3 – 17 years of age | Oral health education, screening, scaling, topical fluoride, sealants |

| Pediatric Specialist Services Dental Program |

|

|

| Early Childhood Dental Initiative | 15- and 18-month-old babies at Public Health immunization clinics |

Screening, risk assessment by dental hygienists |

| Newfoundland | ||

| Children’s Dental Health Program |

|

|

| Nunavut and the Northwest Territories | ||

| Non-Insured Health Benefits Program |

Registered First Nations and Inuit |

Emergency, diagnostic, restorative, endodontic, periodontal, prosthodontic, oral surgery, orthodontic services |

| Yukon Territory | ||

| Children’s Dental Health Program (Yukon Health and Social Services) |

Two programs:

|

|

|

Sources: Adapted from Rowan-Legg A; CPS, Community Paediatrics Committee. Oral health care for children – a call for action. Paediatr Child Health 2013;18(1):37-43; Canadian Institute for Health Information. Treatment of preventable dental cavities in preschoolers: A focus on day surgery under general anesthesia. Appendix B:21-3. |

||

Other barriers

More information on how to recognize and address potential barriers to health care in newcomer patient and on using interpreters can be found on this website.

Selected resources

- The CPS position statement Oral health care for children – a call for action.

- The AAP’s web pages on Children’s Oral Health and their Protecting All Children’s Teeth Curriculum (PACT)

- The WHO’s web information on oral health.

References

- Reza M, Amin M, Sgro A, et al. Oral Health Status of Immigrant and Refugee Children in North America: A Scoping Review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2016;82:g3

- World Health Organization. Global oral health status report: towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

- American Academy of Paediatrics. Oral Health and Protecting All Children’s Teeth Curriculum (PACT)

- McNally M, Matthews D, Pottie K, for the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. Appendix 16: Dental disease; Evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2011;183(12):E824-925.

- Health Canada. Summary report on the findings of the oral health component of the Canadian Health Measures Survey 2007–2009. Ottawa, Ont.: Health Canada, 2010.

- Werneck RI, Lawrence HP, Kulkarni GV, et al. Early childhood caries and access to dental care among children of Portuguese-speaking immigrants in the city of Toronto. J Can Dent Assn 2008;74(9):805.

- Newbold KB, Patel A. Use of dental services by immigrant Canadians. JCDA 2006;72:143a-f.

- Bisgaier J, Cutts DB, Edelstein BL, et al. Disparities in child access to emergency care for acute oral injury. Pediatrics 2011;127(6):e1428-35.

Reviewer(s)

Jennifer Park, DMD, M. Sc., FRCD(C)

Last updated: June, 2025