Cysticercosis and Taeniasis

Key points

- Taeniasis is an intestinal infection with the adult tapeworm, either Taenia saginata (from cattle), Taenia solium or Taenia asiatica (both from pigs),. Infected individuals often have mild or no symptoms. One dose of oral antiparasitic therapy is very effective in eradicating the parasite.

- T solium infection can lead to cysticercosis. Cysticercosis is a tissue infection with the larval stage (or cysticercus) of this tapeworm .

- Humans are the definitive hosts for these three Taenia species. Eggs released in human stool contaminate the soil and infect pigs and cattle. Porcine cysticercosis is highly endemic in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and South and Southeast Asia. T asiatica is found only in Asia.

- Neurocysticercosis is the most severe form of cysticercosis. It is caused by cysts in the central nervous system and is a major cause of epilepsy (adult onset and, less commonly, childhood onset), in endemic areas. Seizures, headaches and hydrocephalus are the most common manifestations.

- Cases of neurocysticercosis are becoming more common in Europe, the U. S. and Canada because of increased migration and travel.

- Health care providers should understand the symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of this potentially serious condition.

- Consultation with specialists in infectious diseases, neurology and ophthalmology is recommended before initiating antiparasitic therapy.

Taeniasis: Introduction

Taeniasis is caused by intestinal infection with the adult tapeworm: Taenia saginata (from cattle) or Taenia solium (from pigs). Taenia asiatica causes taeniasis in Asia. T. solium takes two distinct forms in the human host:

- Taeniasis: Tapeworm infection of the gut lumen.

- Cysticercosis: Infection of tissues with larval cysts (cysticerci).

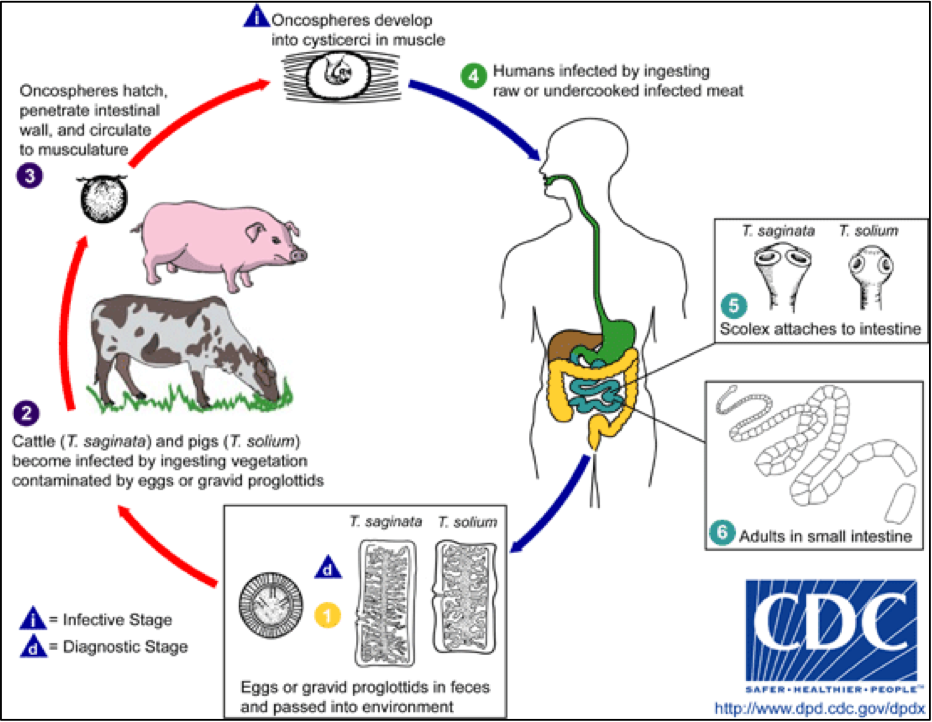

Taenia: Life cycle

Figure 1: Life cycle of Taenia

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DPDx: Taeniasis : www.cdc.gov/dpdx/taeniasis/index.html

Taeniasis is acquired by inadvertently ingesting the cysticerci in undercooked pork (T. solium) or beef (T. saginata). Cysticerci can develop into adult worms, living in the intestine and, if untreated, reach a length of 2 to 8 meters. Six to eight weeks after ingestion, gastrointestinal tract symptoms can occur, such as nausea, diarrhea or constipation and abdominal pain, but many patients remain asymptomatic.

The adult tapeworm releases egg-bearing gravid proglottids (segments) which may look like a white elastic band protruding from the anus or be seen migrating from the anus or in feces. Left untreated a tapeworm can live and produce proglottids for decades.1

Figure 2: Adult Taenia tapeworms

Adults of Taenia spp. Adults can reach a length of 2-8 meters, but the scolex is only 1-2 millimeters in diameter.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DPDx: Taeniasis : www.cdc.gov/dpdx/taeniasis/gallery.html

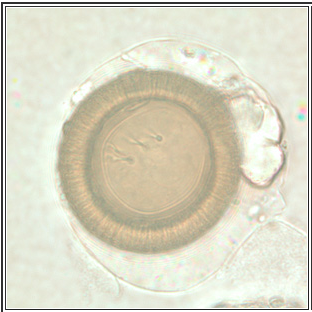

Figure 3. Eggs from T. solium and T. saginata are identical in appearance

Source: Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DPDx: Taeniasis: www.cdc.gov/dpdx/taeniasis/gallery.html

Taeniasis: Diagnosis

Diagnosis of taeniasis (adult tapeworm infection) is based on the presence of proglottids or ova in the patient’s feces or perianal region. Because ova and proglottids are shed intermittently, the sensitivity of stool microscopy for ova is only 26%. Yield is increased if 3 stool samples are submitted on different days. The ova of T. solium and T. saginata are microscopically indistinguishable. Species identification of the parasite is based on the different structures of gravid proglottids and scolex.2

Taeniasis: Treatment

Treatment with oral praziquantel is highly effective for eradicating infection with the adult tapeworm. A single dose of 5 mg/kg to10 mg/kg should be taken with liquids during a meal.

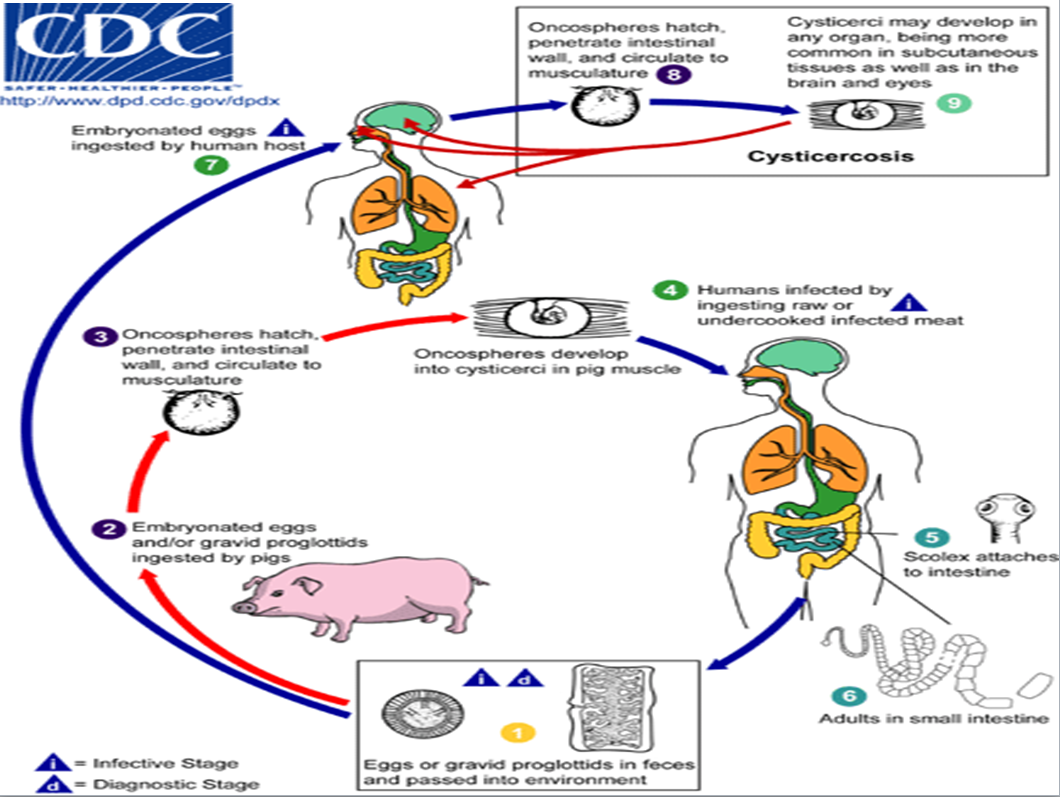

Cysticercosis: Life cycle

T. solium (from pork) is of greater public health concern than T. saginata because human to human transmission of the tapeworm eggs can cause cysticercosis, a serious parasitic disease.1

Figure 4: Life cycle of cysticercosi

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DPDx: Cysticercosis: www.cdc.gov/dpdx/cysticercosis/index.html

Cysticercosis: Acquisition

Cysticercosis in humans is acquired by ingesting eggs of the pork tapeworm (T. solium). Unlike taeniasis, it is not from ingestion of undercooked meat. Eggs are found in the feces of a human infected with tapeworm who may transmit the infection to other people (or pigs) through fecal contamination of soil, water or food. .1 Autoinoculation can also occur. The eggs can live for up to 2 months in water, soil or vegetation.3

Once ingested, the eggs hatch in the small intestine and the larvae migrate to various tissues throughout the body, where they form cysts. This is called cysticercosis. If the cysts are in the brain, the condition is called neurocysticercosis, the most severe form of the disease.

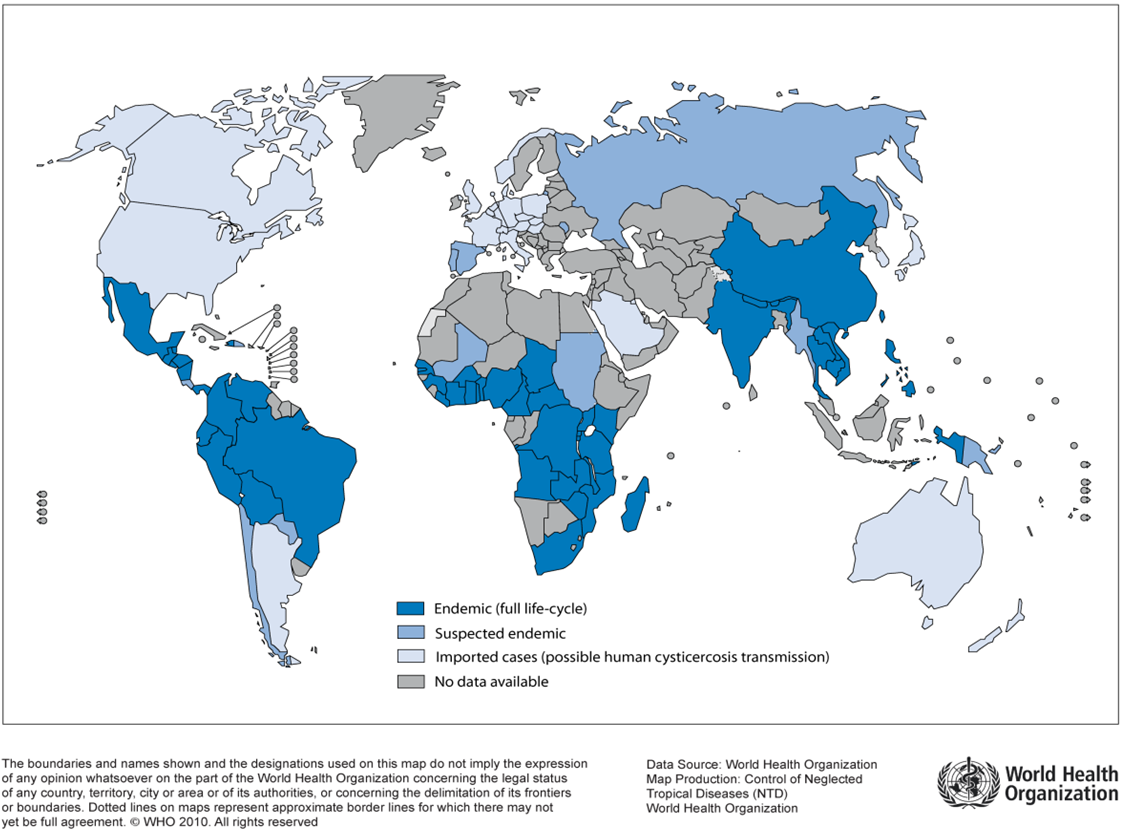

Cysticercosis: Epidemiology

Cysticercosis is highly endemic in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia, as well as parts of Korea, China, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.2 The WHO estimates between 2.5 and 8.3 million people have neurocysticercosis, including both symptomatic and asymptomatic.

Figure 5. Countries and areas at risk of cysticercosis, 2009

Source: Reproduced, with the permission of the publisher, from Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: First WHO report on neglected tropical diseases, 2010. Geneva, WHO, 2010 (http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/2010report/en/, accessed 04 March 2014).

In the developing world, neurocysticercosis is a common infection of the human central nervous system (CNS) and the most frequent preventable cause of epilepsy. Increasing migration from and travel to disease-endemic regions results in neurocysticercosis being seen more often in industrialized countries.

Typical cases in the U.S. have been immigrants from Latin America and Asia who became infected in their home country,2 or who acquired cysticercosis from a close contact in the U.S..

There are limited Canadian data. In 2012, Del Brutto identified a total of 21 articles reporting 60 patients, of whom 40 (67%) were diagnosed in the past two decades. Immigrants accounted for 96% of the 28 cases for whom citizenship information was available.4 It is possible that at least some of the patients may have acquired the disease in Canada from a household contact harbouring the adult T. solium in the intestine.3

Although cysticercosis is uncommon in Canada, health care providers should be aware of its potential to present as afebrile seizures in children and adolescents.

Cysticercosis: Clinical clues

The time between infection and onset of symptoms is variable and people infected with cysticercosis can remain asymptomatic for years.

Clinical manifestations are also variable and depend on the location of the cysticerci and the host’s inflammatory response.2

Figure 6. Neurocysticercosis lesions in the brain

Sources: (L to R) Westchester Medical Centre; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Image Library (PHIL); Cysticercoses Working Group in Peru: /www.cdc.gov/parasites/cysticercosis/index.html

Most symptoms are caused by inflammation around a degenerating or dying cyst, although calcified (dead) cysts can also serve as a seizure focus and enlarging, viable (live) cysts can cause symptoms due to mass effect. Symptoms and signs are listed in Table 1 and described below.

Table 1. Symptoms and signs of cysticercosis

| More common | Less common |

|

|

The infection location that most often, and seriously, prompts medical consultation is the brain. Some patients, including children, experience severe headache (resembling a tension headache or migraine) as their only symptom.2

Epilepsy is present in 70% to 90% of symptomatic patients. Onset typically occurs from 5 to 40 years of age, but seizures have been noted in infants. Seizures are usually focal with secondary generalization, although they can also be focal or generalized.2

Neurocysticercosis can present with signs or symptoms of raised intracranial pressure and altered mental status. Diffuse cerebral edema caused by multiple inflamed cysticerci is known as cysticercal encephalitis.2 Intracranial hypertension, the presence of large basilar or supratentorial cysts or a large numbers of cysts, or cerebral infarction, can all be life-threatening.5

Less frequent manifestations include obstructive hydrocephalus, chronic meningitis, cranial nerve abnormalities and behavioural disturbances. Infected children may develop learning disabilities.

Cysts in the spinal column can cause gait disturbance, pain or transverse myelitis.

Subcutaneous cysticerci produce palpable though painless, mobile cystic lesions that resolve in months to years.6 Subcutaneous disease is more common in Asia and Africa than in the West.2 Skeletal muscle involvement may result in pseudohypertrophy, or weakness with massive infection, or in cigar-shaped calcifications which can be seen on radiographs even without musculoskeletal symptoms.6 Ocular involvement, most commonly involving the retina or vitreous, can reduce visual acuity or cause other visual field defects.7

In a patient with multiple cysticerci, different clinical presentations (eg, brain parenchymal lesaions causing seizures, intraventricular cysts causing hydrocephalus, spinal cord lesions, ocular lesions) can be seen at the same time.

Cysticercosis: Diagnosis

Neurocysticercosis is more difficult to diagnose than many other parasitic infections because parasite eggs may not be present in the patient’s stool and clinical presentations are nonspecific. While enhancing lesions are typical of neurocysticercosis, similar lesions can be seen with tuberculosis, brain abscesses and tumors.2

Consider a diagnosis of neurocysticercosis if your patient:3

- Has a household contact with T. solium infection

- Comes from a region where cysticercosis is endemic

- Travels repeatedly to a disease-endemic region

- Experiences a new onset seizure

- Presents with cystic lesions, solitary enhancing lesions or has punctate calcifications observed on neuroimaging studies

- Has intracranial cystic lesions that resolve after treatment with albendazole or praziquantel

Tests used to detect cysticercosis include doing a biopsy of subcutaneous cysts, immunodiagnosis (finding antibodies or parasite antigens in serum samples) and imaging (radiography, computed tomography [CT] and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]).1

A diagnosis of neurocysticercosis usually requires both CNS imaging and serological testing. A careful history should always be taken, with focus on residence or extended travel in disease endemic countries and the consumption of food prepared by someone who has lived in a high-risk area.8 Advice on taking a history with newcomer families, including the use of interpreters, is available in this resource.

CNS imaging with CT or MRI can be diagnostic if a scolex (the tapeworm’s attachment or holdfast organ, which can have a ‘hole-with-dot’ appearance) is seen on the image.9 An inflammatory reaction to cyst degeneration and resultant edema may appear as a contrast-enhanced ring around the cyst. In children, lesions typically are found within the cortex.2

Serological testing is needed to confirm the diagnosis when neuroimaging indicates the possibility of neurocysticercosis. Antibody assays that detect specific antibody to larval T. solium in serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are the tests of choice. An immunoblot assay is available through the National Reference Centre for Parasitology at the JD Maclean Centre for Tropical Diseases in Montreal (https://www.mcgill.ca/tropmed/services/national-reference-centre-parasitology/immunodiagnostic-service) . Serological testing is less useful when there is a solitary lesion, a finding more common in children, and in people from the Indian subcontinent.5

Seeing a parasite during an ophthalmoscopic examination or in a tissue sample is rare but is definitive for neurocysticercosis.2

Cysticercosis: Treatment

It is possible to have T. solium tapeworm infection (taeniasis) and cysticercosis at the same time, and cysticercosis can represent a spectrum of diseases that differ in optimal management.2 The approach to treatment will depend on the location, number and stage of cysticerci, and on clinical manifestations (especially whether encephalopathy or hydrocephalus is present). Initiation of anthelmintic chemotherapy is not urgent and can be planned while initial medical care is focused on symptom control (eg, starting antiseizure medication or neurosurgical intervention for hydrocephalus).5

Because life-threatening side effects can occur with antiparasitic therapy, consulting with specialists in infectious diseases, neurology and ophthalmology (to rule out intraocular cysticerci) before initiating such treatment is critical.

Two antiparasitic drugs albendazole and praziquantel –are cysticidal, .3 The perilesional inflammation thatresults can worsen a patient’s condition initially or even cause death depending on the location of viable cysts.5

Studies suggest that albendazole is superior to praziquantel in reduction of live cysticerci. It has the added advantage of better penetration into CSF, increased serum and CSF levels when administered with dexamethasone, and fewer drug-to-drug interactions with anticonvulsants. Dexamethasone, phenytoin and carbamazepine may decrease praziquantel levels.10 (reference updated)Typically albendazole is given at a dose of 15 mg/kg/day divided in 2 doses orally [maximum 800 mg/day] for 2 weeks; however duration may vary with the number and location of cysts, Steroids and anticonvulsants are administered first and symptoms controlled before initiating antiparasitic therapy . The duration of steroids is generally 1 – 2 weeks with a slow taper.11

Intraventricular cysts are usually treated by surgical removal, preferably by endoscopy. Anthelmintics are relatively contraindicated, because the resulting inflammatory response can precipitate obstructive hydrocephalus. If cysticerci cannot be removed easily, hydrocephalus should be corrected by placing intraventricular shunts. Adjunctive chemotherapy with anti-parasitic agents and corticosteroids may decrease the rate of subsequent shunt failure.2

Cysticercosis of the eye, spine or subcutaneous tissue is usually treated by removing the cysticerci surgically. Albendazole or praziquantel should not be used to treat ocular or spinal cysts, even in conjunction with corticosteroids. Inflammation may cause permanent damage.

Seizures can recur for months or years. The decisions to discontinue an anticonvulsive regimen is made on a case by case basis. However, anticonvulsant therapy is generally recommended until the patient has been seizure-free for at least2 years. Seizure recurrence risk factors include status epilepticus, poor seizure control during treatment, and persistent radiologic and EEG changes.13

Cysticercosis: Prognosis

The proportion of patients who fully recover from cysticercosis, with or without treatment, is unknown.1

The prognosis of neurocysticercosis is extremely variable. Symptomatic patients with single lesions generally do well, are often seizure- free, and may be able to discontinue anticonvulsant therapy within 1 to 2 years. Patients with numerous subarachnoid cysticerci often require repeated courses of therapy and multiple surgeries.2 Mortality is low in patients with parenchymal cysts without hydrocephalus.

Cysticercosis: Prevention

Preventing the transmission of eggs from person to person is key to controlling this disease. Here are some practical steps:

- Identification and treatment of tapeworm carriers is an important Public Health measure that can prevent further cases.8

- Identify and treat individuals with taeniasis.

- Screen individuals with cysticercosis and their close contacts for taeniasis.

- Food preparers can reduce the risk of transmitting enteric diseases, including neurocysticercosis, through good handwashing practices.

- Travelers to areas with poor sanitation should be particularly careful to avoid foods that might be contaminated by human feces such as uncooked vegetables and fruits that cannot be peeled.

Development of an effective vaccine against cysticercosis may provide the best potential tool for eradication of the disease.12

References

- WHO, Neglected tropical diseases: Cysticercosis/Taeniasis.

- Cherry J, Demmler-Harrison GJ, et al (eds.) Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Paediatric Infectious Diseases, 7th edn. Elsevier/Saunders, 2014:3030-40.

- Burneo JG, Plener I, Garcia HH. Neurocysticercosis in a patient in Canada. CMAJ 2009; 180(6):639-42.

- Del Brutto OH. A review of cases of human cysticercosis in Canada. Can J Neurol Sci 2012; 39(3):319-22.

- Krilov LR, Cantey PT, Burke AP. Cysticerosis among parasitic infections targeted by CDC. AAP News 2012;33(10):20.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Taenia solium pathogen safety data sheet – Infectious Substances.

- Garcia HH, Del Brutto OH; Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru. Neurocysticercosis: Updated concepts about an old disease. Lancet Neurol 2005;4(10): 653-61.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Parasites – Cysticercosis: Resources for Health Professionals.

- Del Brutto OH. Neurocysticercosis: A review. ScientificWorld Journal 2012;159821, doi:10.1100/2012/159821

- http://omr.bayer.ca/omr/online/biltricide-pm-en.pdf

- Garcia HH, Nash TE, Del Brutto OH. Clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of neurocysticercosis. Lancet Neurol. 2014 Dec;13(12):1202-15.

- Nash TE, Mahanty S, Garcia HH. Neurocysticercosis - More than a neglected disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7(4): e1964.

- Bustos JA, Garcia HH, Del Brutto OH. Antiepileptic drug therapy and recommendations for withdrawal in patients with seizures and epilepsy due to neurocysticercosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2016 Sep;16(9):1079-85.

Reviewer(s)

- Heather Onyett, MD

Last updated: August, 2020