Supporting breastfeeding among immigrant and refugee mothers

Key points

- Exclusive breastfeeding is the normal and unequalled method of feeding babies for the first 6 months of life. There are very few situations in which breastfeeding is not recommended.

- Breastfeeding may be sustained until a child is 2 years of age and beyond.

- There are many different reasons why women either do not initiate or do not continue breastfeeding.

- A common reason given for not breastfeeding, in both developed and developing countries, is the mistaken perception that a mother’s breast milk will not satisfy infant needs (in terms of quality or quantity). With education, advice and support, most mothers can successfully breastfeed.

- Immigrant mothers are more likely to initiate and continue breastfeeding than Canadian-born women.

- Asking about traditional beliefs and practices around infant feeding and post-natal care can help clinicians better understand a woman’s decisions about infant feeding. In turn, this can help health professionals develop targeted strategies to support breastfeeding in immigrant and refugee women.

Optimal nutrition

Globally, the two leading causes of death for children under 5 years of age are pneumonia and diarrhea, conditions that are also associated with undernourishment. Both conditions can improve with breastfeeding.1 Breast milk’s unique and complex composition includes specific maternal antibodies and other bioactive factors, such as anti-infective immunoglobulins and white blood cells.2 Breastfeeding has also been associated with reduced risk of SIDS.3

Mothers also benefit from breastfeeding,4 with decreased risks of premenopausal breast cancer5, ovarian cancer, retained gestational weight gain, T2DM and metabolic syndrome.6,7,8

The multiple benefits of breastfeeding to babies and mothers are detailed in Nutrition for healthy term infants: Recommendations from birth to six months, a joint statement from Health Canada, the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS), Dietitians of Canada and Breastfeeding Committee for Canada, updated in 2012.

Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended as the normal and unequalled method of feeding healthy term infants for the first 6 months of life.9,10

Babies who are exclusively or partially breastfed should receive a supplement of vitamin D until they are one year of age.9,11 This supplement is particularly important for dark-skinned mothers and babies who are at higher risk of vitamin D deficiency, especially those living in northern Canada where climate limits endogenous vitamin D production. The CPS has specific recommendations for vitamin D supplementation.

By 6 months, babies are ready to be introduced to the first nutritious, iron-rich foods to complement continued breastfeeding. According to Canada’s Food Guide to Healthy Eating, first foods may include meat, meat alternatives and iron-fortified cereals. The appropriate time to introduce complementary foods also depends on the infant's signs of readiness, which may be a few weeks before or just after the sixth month mark.9

Women can continue breastfeeding as part of providing a nutritious diet until children are 2 years of age and beyond.

Breastfeeding rates in immigrant and refugee women

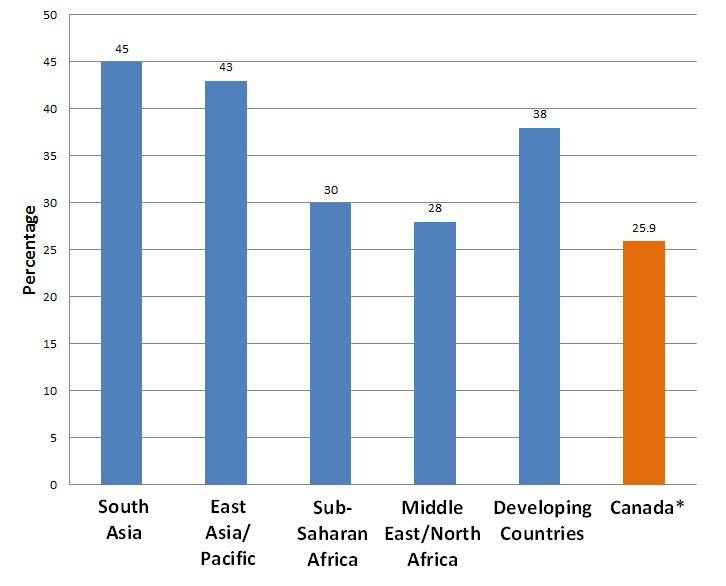

According to a 2010 survey conducted by Toronto Public Health and Access Alliance, recent immigrant mothers (those living in Canada for 5 years or less) were 1.6 times more likely than mothers born in Canada to sustain breastfeeding to 6 months. While most new mothers in Canada initiate breastfeeding, only a minority (about one-quarter) sustain exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months. More information on Canadian trends in breastfeeding practice is available from the Canadian Community Health Survey.

Around the world, in regions that include developing countries and those with a low-to- medium human development index (HDI), sustained breastfeeding rates are generally higher than in Canada. Knowing this can help clinicians encourage newcomer mothers to continue breastfeeding.

| Figure 1: Percentage of babies exclusively breastfed to 6 months, by region, 2000-2006. |

|

| Sources: Adapted from UNICEF Progress for Children: A world fit for children statistical review, MDG1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, 2007. *Canadian rate is from Health Canada, Duration of exclusive breastfeeding in Canada: Key statistics and graphics (2009-2010). |

Common reasons for not breastfeeding

Decisions about breastfeeding are affected by many factors, including:

- Individual and family variables, such as the baby and mother’s environment, previous breastfeeding experiences, partner support, the influence of other family members (especially grandmothers and male partners); and

- Societal variables, such as whether breastfeeding is seen as 'normal', whether there are 'baby-friendly' spaces to breastfeed, and whether mothers have support in the workplace.

A common reason for not initiating or sustaining breastfeeding, in both developed and developing countries, is the mistaken perception that either the quality or quantity of a woman’s breast milk will not satisfy her infant’s needs.

Here are some of the other reasons commonly cited for not breastfeeding:

- Fear that breast milk cannot meet their baby’s nutritional needs.

- Fear that breastfeeding will be difficult or painful.

- Illness or poor health in the mother.

- Belief that early supplementation is necessary. The practice of giving water to newborns and young infants is widespread in many regions of the world.

- Cultural beliefs and traditions. For example, Bedouin women take a 40-day rest period postpartum. Breastfeeding duration depends on the help they receive during that period.

- Pressure on mothers to care for other family members, which is strong in some cultures and may present logistical and time challenges to breastfeeding.

- Belief in misleading marketing messages that suggest that breast milk substitutes are equivalent in quality to breast milk.

- Feelings of modesty, embarrassment or fear of breastfeeding in public spaces.

- Lack of access to breastfeeding information or support, such as a lactation consultant, in their own language.13

Some studies have found that women are less likely to breastfeed if they give birth in a hospital that does not encourage or teach about breastfeeding, or where sample formula is provided to supplement nursing.14

Breastfeeding provides economic benefits to families by eliminating the need to buy formula and by helping to prevent childhood illnesses, thus saving on medication costs and time lost from work. Yet for families new to Canada, economic pressures may factor into the decision not to breastfeed. Newcomer mothers and fathers may not qualify for maternity or parental leave through employment insurance. It may be financially necessary for both parents to work. Some mothers may be looking for work while they are pregnant or soon after birth. Women of lower socioeconomic status may be working in jobs where schedules, transportation and other factors make regular breastfeeding or pumping more difficult.13 Newcomer mothers may not have extended family members nearby who can provide help.

Being aware of these possibilities can help clinicians to support new immigrant families. Among immigrant households facing food insecurity, breastfed infants have been shown to be in better health, with fewer hospitalizations and enhanced growth compared with non-breastfed infants, along with some protection against overweight and obesity.15

No rest for the weary

A Vietnamese mother gives birth to a term newborn and decides to formula-feed because she is returning to work and does not feel she will have enough milk to sustain breastfeeding. You ask about specific traditional practices related to pregnancy and birth.

She describes the Vietnamese am/duong theory of health, equivalent to the Chinese yin/yang principle. During pregnancy and after birth, traditional practices aim to restore the balance of hot and cold in the body.

In Vietnam, a hundred-day period allows the new mother to rest, restore 'vital energy', receive emotional and domestic support from her mother or other female family members, and perform postnatal protection rituals for her health. This prevents excessive 'cooling' of her body and assures fresh, nourishing and abundant maternal milk for her baby.

This rest period is not possible because she must return to work soon, and is living in Canada far from her family. She perceives that her health and the quantity and quality of her milk will be jeopardized.16

Learning points:

- The actual reasons for not breastfeeding are often more complex than initial responses suggest.

- Emotional and domestic support is important in most cultures during the postpartum period.

- Understanding the motivation behind not breastfeeding can help the health professional to develop better, targeted strategies for breastfeeding support.

Early supplementation

Exclusive breastfeeding means a baby receives only breast milk and no other fluids, including water.10 Breast milk provides for almost all the baby’s nutritional needs. The one exception is met by giving vitamin or mineral supplements in the form of drops or a syrup, or an oral rehydration solution.9 Breastfed babies should be given supplementary vitamin D drops.

Supplementation with any other liquids or foods can negatively affect breastfeeding success. Early supplementation has been associated with earlier weaning and an increase in the likelihood of developing insufficient milk syndrome.17,18

Common supplementary foods vary around the world but include:

- rice, mashed bananas and thin porridge in Indonesia.

- glucose mixed with a packaged cereals or with gruel made from maize meal in Kenya.

- herbs mixed with cow’s milk “to prevent stomach aches [or] make the child grow” in Mali.19

- local herbal drops (janamghuit) around one month of age to “clean the stomach of infants and … remove unnecessary contents by inducing vomiting” in Nepal.12

- watered-down millet or maize porridge in African countries.

Fluids (including water) can make a baby feel full and solids may be difficult to digest, leaving a baby feeling too uncomfortable to breastfeed. Babies who receive supplementary liquids or foods in the early months spend less time breastfeeding, suckle less intensively and, as a result, their mothers' breasts are less stimulated to produce milk.

When should a woman not breastfeed?

There are very few situations in which a woman should not breastfeed or where breastfeeding should be restricted.20 Most medications are safe to use by breastfeeding mothers or a safe alternative is available. Both the breastfeeding mother and her baby can receive routine recommended vaccines.20 If breastfeeding is interrupted, mothers should be encouraged and supported to pump or ‘express’ breast milk to help maintain milk production.

- HIV infection: Breastfeeding by women with HIV infection is contraindicated in Canada and other developed countries.

- Human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1, HTLV-2): Breastfeeding is contraindicated.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV-1, HSV-2): Encourage continued breastfeeding unless there are lesions on a mother’s breasts. Clarify that skin-to-skin contact with or feeding from a breast with lesions must be avoided. The mother can pump and discard milk from the infected breast and continue breastfeeding with the other breast until lesions are healed (crusted).

- Mastitis and breast abscesses: Advise the mother to continue breastfeeding unless there is obvious pus, in which case she should pump and discard milk from the infected breast and continue breastfeeding with the other breast. Antibiotic therapy may be needed to hasten recovery.

- Tuberculosis: The main route of transmission is by airborne microorganisms. With active TB, delay breastfeeding until mother has received 2 weeks of appropriate anti-TB therapy. Provide TB prophylaxis for the infant.

- Maternal medications: Drugs that are contraindicated or should be used with caution during breastfeeding include: antineoplastics and immunosuppressants, ergot alkaloids, gold, iodine, lithium carbonate and radiopharmaceuticals. In mothers with G6PD deficiencies (an X-linked recessive condition most commonly found in African-Americans and people of Mediterranean heritage), primaquine and quinine are contraindicated during breastfeeding. Trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole, sulfisoxazole and dapsone should also be used with caution if the nursing infant has jaundice or a known G6PD deficiency, and also if ill, stressed or preterm. More information on cautions and contraindications is available through the Canadian Paediatric Society and Motherisk.

Maternal HIV infection

Whether or not HIV-positive mothers should breastfeed depends in part on where they live.

- In resource-limited settings, such as in some developing countries: The World Health Organization recommends that HIV-positive women or their HIV-positive infants take antiretroviral drugs throughout the period of breastfeeding and until the child is 12 months old. Infants can benefit from breastfeeding with very little risk of becoming infected with HIV.21 The CPS endorses this recommendation.20

- In resource-rich settings: In Canada, where a safe and culturally acceptable substitute for breast milk is available, the CPS recommends against breastfeeding because HIV transmission to infants has been documented.

Encouraging breastfeeding

Health professionals need to support mothers in their infant feeding choices. Breastfeeding is the healthiest option for both mothers and infants, and it should be considered the normal way of feeding babies, and supported and encouraged accordingly. Changes in maternity care practices, such as the Baby Friendly Initiative (BFI) and ‘rooming-in’ for mothers and babies in hospitals and birthing centres, are shown to increase breastfeeding initiation and duration.

Here are some suggestions for creating an environment that supports breastfeeding.

Tips for practitioners

In your practice:

- Use active, non-judgemental questioning to help learn about feeding practices, and be respectful of cultural practices and traditions. Determine the mother’s plans and reasons for feeding practices, and consider particular obstacles related to work and time pressures. Read more about delivery of culturally competent care.

- Ask about early supplementation practices in the parent’s region of origin.

- Consider enlisting the support of the other family members. In some cultures, other family members may play an important role in decisions about infant feeding.13 Read more about the influence of culture on decision-making on this website.

- Provide information and instruction: in the mother’s own language if possible. Involve a professional interpreter when language barriers exist.

- Become knowledgeable in the principles and management of lactation and breastfeeding: Follow a training course, or collaborate with a lactation consultant.

- Develop the skills necessary to assess the adequacy of breastfeeding, such as: ensuring a good latch and positioning of the baby; evaluating hydration, normal stooling patterns, jaundice and weight gain; and managing different lactation problems.

- Respect the WHO International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes, especially the provisions to limit marketing and distribution to pregnant women and new mothers.

In your hospitals and communities:

- Support training and education for new and current health care practitioners in breastfeeding and lactation.

- Promote hospital policies that are compatible with the WHO/UNICEF Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding in both hospital and office settings.

- Encourage collaboration with other health practitioners to develop optimal breastfeeding support programs.

- Coordinate with community-based health care practitioners and certified breastfeeding counsellors to ensure uniform and comprehensive breastfeeding support. Examples are public health units, breastfeeding clinics, breastfeeding support drop-ins, phone peer support programs, lactation consultants, the La Leche League, well-baby drop-ins, and so on.

- Promote breastfeeding as the norm for infant feeding: have highly visible non-commercial posters and educational materials available in your office or clinic; evaluate practices in your maternity facilities, offices and communities; advocate to change practices that are not consistent with the BFI. Do not distribute free formula samples.

Tips for communities

Public policies that support breastfeeding include:

- Access to breastfeeding expertise (e.g., a local public health nurse, lactation consultant) to address problems.

- Workplace supports, such as a private room for breastfeeding and expressing milk, and having a place to safely store breast milk.

- Public spaces set aside for breastfeeding mothers, to ensure comfort and privacy.

Selected resources

- American Academy of Family Physicians, 2008. Family physicians supporting breastfeeding. See especially, Breastfeeding in underserved populations.

- Health Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, Dietitians of Canada, Breastfeeding Committee for Canada; Infant Feeding Joint Working Group, 2012. Nutrition for Healthy Term Infants: Recommendations from Birth to Six Months.

- Health Canada, 1997. A multicultural perspective of breastfeeding in Canada

- Country-specific information on common foods, rates of breastfeeding and young child feeding practices are available from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the UN.

- Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Breastfeeding: A Guide for the Medical Profession, 7th edn. Maryland Heights, MI: Elsevier, Mosby, 2011.

- UNICEF. Progress for Children: A world fit for children statistical review, MDG1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, 2007.

Handouts

- Best Start Resource Centre, 2010. Giving birth in a new land. A booklet containing information for newcomer women who are pregnant and expect to deliver their baby in Ontario. Includes information on local practices related to the prenatal and postnatal period, as well as services and resources available. Available in print and PDF in multiple languages.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Breastfeeding and Feeding your baby in the first year.

Web resources

- Best start: Ontario’s Maternal Newborn and Early Child Development Resource Centre

- Breastfeeding Committee for Canada

- Canadian Breastfeeding Foundation

- Canadian Lactation Consultant Association

- Health Canada, Infant feeding

- INFACT Canada: Infant Feeding Action Coalition

- La Leche League Canada

- Motherisk

- Public Health Agency of Canada, Breastfeeding and infant nutrition

DVDs/videos

- Breastfeeding Inc. Dr. Jack Newman’s visual guide to breastfeeding, with Edith Kenerman. In English and French, with subtitles in Spanish, Portuguese and Italian. Available for purchase.

- Standford University, 2007. Getting started with breastfeeding.

- La Leche League, 2010. Breastfeeding mothers

- Quebec Breastfeeding Support Group Committee, 2007. Bringing baby to the breast and Becoming Parents… nursing baby. Available for purchase.

References

- Kramer MS, Kakuma R. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: A systematic review (WHO/NHD/01.08, WHO/FCH/CAH/01.23). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2002.

- Riordan J, Wambach K. Breastfeeding and Human Lactation, 4th edn. Sudbury MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2010.

- Venneman MM, Bajanowski T, Brinkmann B, et al. Does breastfeeding reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? Pediatrics 2009;123(3):e406-10.

- Steube A. The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2009;2(4):222-31.

- Akbari A, Razzaghi Z, Homaee F, et al. Parity and breastfeeding are preventive measures against breast cancer in Iranian women. Breast Cancer 2011;18(1):51-5.

- Stuebe AM, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, et al. Duration of lactation and incidence of type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2005;294(20):2601-10.

- Jordan SJ, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wicklund KG, et al. Breast-feeding and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2012;23(6):919-27.

- Grummer-Strawn LM, Shealy KR, Perrine CG, et al. Maternity care practices that support breastfeeding: CDC efforts to encourage quality improvement. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22(2):107-12.

- Health Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, Dietitians of Canada, Breastfeeding Committee for Canada; Infant Feeding Joint Working Group, 2012. Nutrition for Healthy Term Infants: Recommendations from Birth to Six Months.

- WHO 2008. Exclusive breastfeeding.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health Committee. Vitamin D supplementation: Recommendations for Canadian mothers and infants. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(7):583-9.

- Ulak M, Chandyo RK Mellander L, et al. Infant feeding practices in Bhaktapur, Nepal: A cross-sectional, health facility based survey. Int Breastfeed J 2012;7(1):1.

- American Academy of Family Physicians, 2008. Family physicians supporting breastfeeding.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Nutrition and Gastroenterology Committee, Hospital Paediatrics Section. The Baby-Friendly Initiative: Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding. Paediatr Child Health 2012;17(6):317-21.

- Neault N, Frank D, Merewood A, et al. Breastfeeding and health outcomes among citizen infants of immigrant mothers. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107(12):2077-86.

- Groleau D, Soulière M, Kirmayer LJ. Breastfeeding and the cultural configuration of social space among Vietnamese immigrant woman. Health Place 2006;12(4):516-26.

- Martines JC, Rea M, De Zoysa I. Breast feeding in the first six months. BMJ 1992;304(6834):1068-9.

- Hill PD, Humenick SS, Brennan ML, et al. Does early supplementation affect long-term breastfeeding? Clin Pediatre 1997;36(6)345-50.

- Castle S. Intra-household variation in illness management and child care in rural Mali. Doctoral thesis, Center for Population Studies, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 1992.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. Maternal infectious diseases, antimicrobial therapy or immunizations: Very few contraindications to breastfeeding (Addendum, June 2011). Paediatr Child Health 2006;11(8):489-91.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV and infant feeding 2010: Principles and recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a summary of evidence.

Other works consulted

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012;129(3):e827-e841.

- Arabi M, Frongillo EA, Avula R, et al. Infant and young child feeding in developing countries. Child Dev 2012;83(1):32-45.

- Bartick M, Stuebe A, Shealy KR, et al. Closing the quality gap: Promoting evidence-based breastfeeding care in the hospital. Pediatrics 2009;124(4):e793-e802.

- Choudry K, Wallace LM. ‘Breast is not always best’: South Asian women’s experiences of infant feeding in the UK within an acculturation framework. Matern Child Nutr 2012;8(1):72-87.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee. Weaning from the breast. Paediatr Child Health 2013;18(4):210.

- DiGirolamo AM, Grummer-Strawn LM, Fein SB. Effect of maternity-care practices of breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2008;122(Suppl 2):S43-9.

- DiGirolamo AM, Grummer-Strawn LM, Fein SB. Maternity care practices: Implications for breastfeeding. Birth 2001;28(2):94-100.

- Dillon JC, Imbert P. L’allaitement maternal dans les pays en développement évolution et recommandations actuelles. Med Trop 2003;63:400-6.

- Hurley KM, Black MM, Papas MA, et al. Variation in breastfeeding behaviours, perceptions, and experiences by race/ethnicity among a low-income statewide sample of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) participants in the United States. Matern Child Nutr 2008;4(2):95-105.

- Obermeyer CM, Castle S. Back to nature? Historical and cross-cultural perspectives on barriers to optimal breastfeeding. Med Anthropol 1996;17(1):39-63.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Family database. CO1.5: Breastfeeding rates.

- UNICEF. Breastfeeding—Impact on child survival and global situation.

- UNICEF U.K., The Baby-Friendly Initiative. Does Breastfeeding Reduce the Risk of SIDS?

- World Health Organization (WHO). Baby-Friendly hospital initiative. Revised, updated and expended for integrated care.

- WHO. Evidence for the ten steps to successful breastfeeding.

- Zhou Q, Younger KM, Kearney JM. An exploration of the knowledge and attitudes towards breastfeeding among a sample of Chinese mothers in Ireland. BMC Public Health 2010;23(10):722.

Reviewer(s)

- Danielle Grenier, MD

- Julie Bailon-Poujol, MD

- Élisabeth Rousseau Harsany, MD

Last updated: February, 2023