Using Interpreters in Health Care Settings

Key points

- Accurate assessment of any newcomer child or youth requires complete, optimal communication without misunderstandings on either side.

- Whenever possible, engage a trained cultural interpreter for your newcomer patients.

- Using a patient’s family members or friends as interpreters carries certain risks. In particular, avoid the use of children and youth as interpreters.

- While online tools can bridge communication gaps when professional interpretation is unavailable, providers must remain aware of their limitations and be cautious of potential for errors.

Many newcomers to Canada may lack sufficient English or French language skills to understand a health professional’s questions or to provide a thorough medical history. Miscommunication can increase the risk of medical errors[1][2], inappropriate treatments,[3][4] and unplanned emergency room visits/admissions[5][6].

Communication with immigrant and refugee families can be seriously impaired if a health care provider is unaware of or insensitive to the role of culture in formal interactions. Cultural interpreters can facilitate verbal and nonverbal communication and mediate concepts and cultural practices as needed.

Interpreter or translator? Each profession involves different skills.

An interpreter works with spoken language, translating and mediating between two languages in both directions in real time. A translator deals with written language and clear, accurate expression in written form, usually in one direction and typically, from a source language into their own native tongue.[7]

In both professions, understanding meaning and nuance of one language and being able to express them in another language are crucial skills. Often, this process requires understanding the culture behind each language.

Roles of the cultural interpreter

Cultural interpreters can facilitate clinician–patient interactions in several ways. In any office visit between a health professional and newcomer family members, a skilled interpreter can:

- Help ensure that everyone understands both words and meaning in the moment, as they are being used.

- Provide a clear and precise interpretation of the care provider’s questions and the family’s answers, while being open to additional questions about what patient (or practitioner) responses might mean.

- Facilitate, but not lead, the communication process. An interpreter should not be ‘in charge’ of an interview, which is a risk if the interpreter was a health professional in their home country.

- Understand the family’s situation and provide relevant cultural context for the clinician (e.g., why a particular family is responding a certain way during an interaction).

- Help the clinician avoid culturally inappropriate actions or words and clarify any misunderstandings on either side.

- Explain the role of the clinician to the family and encourage them to ask questions.

- Respect the confidentiality and integrity of everyone involved. An experienced interpreter will often start an office visit with introductions, explain their own role, and provide assurance that everything to be discussed will be kept private and confidential.

An interpreter can also help establish links within the family’s local cultural community, if such a network is available and the family consents to this level of involvement.

Skills and qualities to look for

A highly skilled interpreter possesses a wide range of skills and abilities, including:

- Professional training and certification.

- A solid grounding in health issues and a clear understanding of medical terminology.

- Some knowledge of related language families and dialects.

- An ability to interpret nonverbal expression (e.g., speech patterns, gestures and facial expressions).

- Some awareness of intercultural issues (e.g., different value systems, the role of individual family members, common taboos, and attitudes toward authority).

- Self-confidence, integrity, attention to detail, and flexibility.

- A sound grasp of Canadian health care settings and processes.

An interpreter may have been a health professional or teacher in their home country, but not yet able to practice their profession in Canada.

Newcomer families may be especially sensitive about sharing medical information. Clinicians must ensure that an interpreter is acceptable to the patient’s family. If an interpreter comes from a rival background—tribal, ethnic, clan or other—the family may not trust them. In such cases, you may need to stop the interview, excuse the interpreter, and start afresh.

Determine whether an interpreter’s services are needed at the first appointment. This allows enough time to find and book an interpreter.

Finding an interpreter

Unfortunately, there is no national standard to ensure availability of interpreters in health settings, which varies based on province and health care setting. While all provinces have some degree of support for language interpretation in government-supported primary care and hospital settings (summarized in Table A1 of Arya et al.’s environmental scan)[8], community clinics are often not included in these arrangements. For these settings, enlisting the help of a professionally trained cultural interpreter who works with a hospital, local health department or community cultural organization is the best option. Often, these professionals are designated specifically for work with one or more cultural, language or ethnic groups. They are available by appointment and remunerated on an hourly basis. Greater public funding is needed to improve access to interpreter services.

Using untrained interpreters

If professional interpretation is unavailable, the next best option is for the family to bring a trusted relative or friend to act as an interpreter. Clarify that they should choose someone they trust with the family’s confidential medical information. Also, bear in mind the potentially protective bias of a family interpreter: they might withhold or change information to avoid conflicts. A trusted community representative is often preferable to a family member. Using an untrained interpreter, such as family, friends, or health care workers, is riskier, and health professionals need to take extra care to ensure that their communications are being well understood.[9]

It is best practice to avoid using children or adolescents as interpreters, which is supported by both the Canadian Paediatric Society and the American Academy of Pediatrics.[10] Using children or adolescents as interpreters can affect the reliability of the information received and pose an unfair burden for a child. For example:

- The reliability of information they provide may be highly questionable. Children may not be aware of all relevant information, may not be confident or fluent enough in both languages to translate accurately and may alter the meaning of communications to protect family members.

- Communicating sensitive health information can be stressful for children.

- Interpreting for parents can disrupt the parent and child roles within the family, affecting dynamics adversely.

- If there is some kind of negotiation or debate involved, a child may be forced to play the role of 'broker', with loyalties divided between a health professional and the family.

In case of emergency

Providers may be tempted to use online translation tools such as Google Translate or ChatGPT. While these tools may help cover gaps where interpretation and translation is unavailable, providers should understand their limitations. Preliminary studies have shown that while AI tools perform well in limited settings (e.g., discharge instructions) for common languages such as Spanish and Portuguese, they perform significantly worse for other languages like Farsi, Armenian, and Haitian Creole.[11][12] Health care providers should be cautious when applying these tools in untested settings. Consider using back translation or multiple online tools to verify the translation’s accuracy.

These websites have aggregated free online translations of health conditions and information handouts:

- MedlinePlus

- HealthLink BC

- Health Info Translations

- EthnoMed

- Victoria State Government

- Hospital for Sick Children

Using an interpreter appropriately

To make involving an interpreter a positive experience, health professionals can take these steps.

When booking the appointment

- Determine whether an interpreter is needed at time of appointment. This allows enough time to find and book the most competent interpreter available.

- Ask the child or youth if they would prefer a male or female interpreter (if there is a choice).

- If possible, allot extra time for a brief consultation with the interpreter beforehand, for the medical visit itself – with interpretation added – and a quick debriefing afterward. These interviews easily take twice as long as more typical patient visits.

- If you and the newcomer family have found a trusted interpreter, try to use the same person for all of their visits.

Before the office visit

- Be respectful of the interpreter’s time: they may have several other appointments scheduled that day. Avoid delays in your own appointment schedule.

- Speak with the interpreter beforehand to discuss the goals of the visit and how best to achieve them. Emphasize that families must make decisions for themselves about medical matters.

During the visit

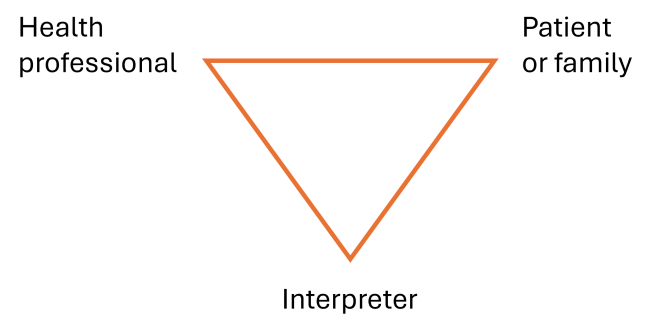

Figure 1: Triangular Seating Arrangement

- Use a triangular seating arrangement, so that everyone can see non-verbal cues, as illustrated in Figure 1.

- Introduce the interpreter and the family. Ask the interpreter to describe their own role, particularly if the family is meeting them for the first time.

- Before starting, be sure to ask the family if they feel comfortable working with this person.

- Ask the parents how much of the discussion they want interpreted. Some parents understand but have difficulty expressing themselves in English or French. They can choose to have only their answers interpreted. If they hesitate, explain that the interpreter will interpret everything.

- Explain your own role as clinician and the purpose of the visit.

- Maintain responsibility for the visit. The interpreter’s role is to convey information accurately, not to provide medical or other explanations.

- Encourage the interpreter to intervene if a misunderstanding occurs or seems likely.

- Many newcomer families understand some English or French. Clinicians should not carry on a separate discussion with the interpreter in a family’s presence without first explaining why. Similarly, clinicians should ask the interpreter to explain the nature and content of any extended discussion with the family.

- When the clinician can direct questions to an adolescent patient in English or French and understand responses, be sure to ask a less fluent parent how much of what is asked or answered should be interpreted for their benefit.

- Look at family members when speaking to them and while the interpreter speaks. Speak directly, using “I” and “you” whenever possible.

- Speak slowly and clearly. Use short sentences, pause frequently to allow the interpreter to translate, and give only small amounts of information at a time.

- Avoid idioms, jargon, slang, abbreviations, acronyms and jokes, which may cause confusion.

- Repeat important instructions and explanations to reinforce messages. If miscommunication is suspected, reiterate with different wording. Ask the patient, parent or caregiver to repeat the information back to you if you think they didn’t understand.

- Allow time for the family to ask questions.

After the visit

- Provide the newcomer family with printed material in their own language if available. Also include written information or fact sheets on family health issues in English or French for review at home.

- When appropriate, ask the interpreter to write down instructions for the family.

- Ask if the interpreter can assist the family with scheduling follow-up appointments with the office receptionist, if needed.

- If possible, arrange for the interpreter to accompany the family for lab tests or to the pharmacy.

- Use the same trusted interpreter for all office visits with this child and family, if possible.

References

- Khan A, et al. Association between parent comfort with English and adverse events among hospitalized children. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(12):e203215.

- Stokes SC, Jackson JE, Beres AL. Impact of limited English proficiency on definitive care in pediatric appendicitis. J Surg Res. vol. 2021;267:284–92.

- Gutman CK, et al. Race, ethnicity, language, and the treatment of low-Risk febrile infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2024;178:55–64.

- Zamor R, et al. Language barriers and the management of bronchiolitis in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Pediatr, vol. 2020;20:356–63.

- Portillo EN, et al. Association of limited English proficiency and increased pediatric emergency department revisits. Acad Emerg Med, 2021;28(9):1001–11.

- Gallagher RA, et al. Unscheduled return visits to the emergency department: the impact of language. Pediatri Emerg Care. 2013;29:579–83.

- Allen MP, et al. Language, interpretation, and translation: a clarification and reference checklist in service of health literacy and cultural respect. NAM Perspect, 2020 Feb 18.

- Arya AN, et al. Medical interpreting services for refugees in Canada: current state of practice and considerations in promoting this essential human right for all. Int J Environ Res and Public Health, 2024;21(5):588.

- Karliner LS, et al. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A Systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727–54.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Paediatric Workforce. Ensuring culturally effective pediatric care: implications for education and health policy. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1677–85.

- Taira, BR, et al. A pragmatic assessment of Google Translate for emergency department instructions. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3361–5.

- Brewster RCL, et al. Performance of ChatGPT and Google Translate for pediatric discharge instruction translation. Pediatrics. 2024;154(1):e2023065573.

Reviewer(s)

Henry Li, BSc, MD

Last updated: December, 2025