Adaptation and Acculturation

Key points

- Adapting to a new country is a process that can be broadly divided into four stages. It is helpful to know where your newcomer patient is in this process, so that you can help them prepare for the challenges and opportunities ahead. Depending on where they are in the resettlement process, you may also need to tailor certain health messages.

- The starting points for adapting to life in Canada vary according to several factors: where people have come from, their migration experience (why and how did they come here?), their plan for the future, and current living conditions. There are many local resources that can help families adapt. It is important to be familiar with and help connect newcomers to the resources in your area, including social workers and settlement agencies.

- Newcomers to Canada face many changes in their lives. They may maintain familiar medical practices based on their culture and religion, such as traditional healing or therapies that, in many situations, can be helpful. Children and youth may feel ashamed that they don’t know about popular music or television shows, or find it difficult to dress like their new peers. Be sensitive to what may be comfortably familiar and uncomfortably new, and offer gentle advice or refer newcomers to groups or services that can help.

- Keep an open mind when speaking with newcomers. Always verify that you have understood their ‘agenda’ and messaging, and make sure that they understand what you have tried to communicate. The fear of not integrating successfully may lead newcomers to agree with a health professional when, in fact, the meaning of what they’ve agreed to is still unclear.

- Remember that many newcomers have survived very difficult circumstances through their own resilience. Helping newcomer patients to identify and tap into their own strengths can facilitate improved health and adaptation.

Newcomers and their migration story

Newcomers to Canada are an extremely diverse group. Their migration stories (why and how they’ve come to Canada) are just one of many factors influencing health, while other social determinants, such as education, income, housing and food security each play a role. The social determinants of health are grouped into 5 categories; economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context.

Consider two different scenarios:

- A brother and sister come to Canada from a cosmopolitan city in Eastern Europe. Their mother is a doctor; their father, a lawyer. The parents organized and self-financed the entire immigration process and emigrated solely to offer a better life for their children.

- Two newcomer siblings, a boy and a girl, come to Canada from the mountains of Burma, where they spoke Chin. Their mother is illiterate. Forced into hiding with their mother, the children had to watch their father being beaten to death before they were able to flee to a refugee camp on the Thai border. They did not attend school in the refugee camp.

Even if the migration experience appears to be relatively smooth, as for the family from Eastern Europe, there are almost always difficulties associated with migration, including loss of status, unfamiliar social systems, and distance from friends and family. Children are often acutely aware of their parents’ sacrifices and may feel guilty.

The Burmese family's experience will likely have a profound effect on both their health and the speed with which they adapt. The children’s education was interrupted, their father is dead, and their mother was disadvantaged in her first language. These children are likely to remain poor while growing up. In the absence of their father, the eldest son may assume the roles of protector, head of the household and, later, provider. Consequently, his education may be sacrificed.

Many people who reach a Canadian border and then claim refugee status, embark on a protracted application process. If their applications are refused, the consequences of returning to their home country may be frightening to the extent that they remain in Canada without status or health care insurance. An unsuccessful refugee claim and undocumented migration are tangled threads in an already complex migration story: they often lead to housing insecurity, low income, fear of discovery, the threat of deportation, limited access to health care and eventually, poverty.

Health care professionals can improve patient treatment and better meet the needs of newcomers by being aware of their migration story and of how each story may affect their current status in Canada, their state of health or recovery, and their ability to navigate the health care system.

How healthy are newcomers to Canada?

Some studies show that newly arrived immigrants to Canada have better self-reported health and lower use of health care services than native-born Canadians.1,2 This so-called “healthy immigrant effect” is controversial, however, and is known to vary among specific groups. The vast majority of newcomers to Canada choose to come here, have successfully negotiated the immigration process, and have passed the required medical exams. It’s not surprising that they seem healthy, are able to access care as needed, and adapt quickly. The trouble is, not all immigrants fit this profile.

Although refugees, as a group, face greater challenges than other newcomers, they also demonstrate the healthy immigrant effect. However, while it is possible that there are real differences in health status, refugees may also be more reluctant to disclose personal information and to avoid health care services because of language difficulties, lack of insurance, or for cultural reasons (e.g., perceptions of health, health care and disease, family dynamics or social norms). More information about barriers to access of health care for newcomers is available on this site.

The healthy immigrant effect declines with years lived in Canada. Non-European female immigrants experience the greatest deterioration in self-reported health after arrival in Canada, and European males the least. Causes of this decline are thought to be related to factors such as changes in diet, activity levels, use of tobacco or alcohol, and changing socioeconomic status.3-7 It is also possible that newcomers are more likely to report symptoms and to access care in the later stages of adaptation, that is, after they have been in Canada for awhile.

Even though many newcomers appear healthier than the average Canadian when they first arrive, some may have been exposed to diseases that are rare in Canada but common in their home country.8 Detailed information on some of these diseases, and screening for them, can be found elsewhere on this site, and in recent, Canadian evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees from the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health.

Adaptation, acculturation and racial-ethnic identity

Adaptation is the process of change in response to a new environment. It is one component of acculturation, which relates to the change in a group’s culture or the change in individual psychology in response to a new environment or other factors. Racial-ethnic identity development involves identifying with and relating to a specific group, and is found to be associated with particular health behaviours and mental health outcomes.9

The idea of culture adjustment as a process was described in 1955 by Norwegian sociologist Sverre Lysgaard, who proposed a U-curve model with four stages: honeymoon, culture shock, recovery and adjustment.10

The processes of adaptation and racial-ethnic identity development are complex and non-linear. They are complex because they are difficult to measure and extremely variable. They are non-linear because navigating through these steps includes both forward and backward movement, depending on what additional stressors are in the family’s life and how those stressors influence identification with a peer group. Past models of adaptation that have influenced policy and practice were linear, with immigrants being considered as more (or less) ‘acculturated’ or ‘assimilated’. These models are no longer accepted.

It is challenging to describe any process that is complex and non-linear. How do people who have developed fully in one cultural setting experience and adapt to change when living in a completely different context? Here is one description:11

If culture is such a powerful shaper of behaviour, do individuals continue to act in the new setting as they did in the previous one, do they change their behavioural repertoire to be more appropriate in the new setting, or is there some complex pattern of continuity and change in how people go about their lives in the new society? The answer provided by cross-cultural psychology is very clearly supportive of the last of these three alternatives.

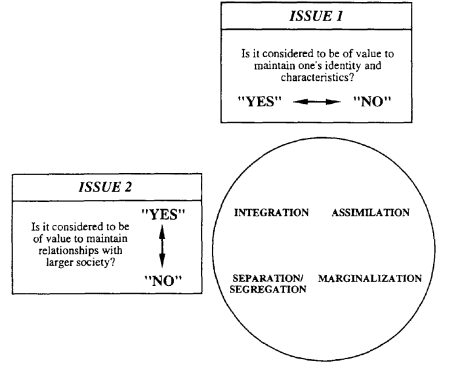

Figure 1 shows the different responses to acculturation, where the value of maintaining an ‘old’ culture is balanced with exposure and adaptation to the ‘new’.11 The ‘choice’ of one response over another can change, depending on shifting of stressors. One model suggests four types of acculturation:

- Assimilation: An original culture is rejected and a person only participates in the new culture.

- Integration: An original culture is retained while accepting the new culture.

- Separation/segregation: The original culture is retained and the new culture rejected.

- Marginalization: Both the original culture and the new culture are rejected.

| Figure 1: Acculturation strategies |

|

| Source: Berry, JW. “Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation.” Applied Psychology 1997;46(1):10. With permission. |

Compared with other acculturation styles, integration is associated with:

- lower levels of stress and higher levels of functioning in adults,12

- lower levels of risk behaviour and more positive attitudes toward health care workers in youth,13,14

- better psychological and sociocultural outcomes in youth.9

Newcomers’ ability to shift their cultural identity and engage with people outside of their ethnic group helps determine how successfully they integrate into their new homeland. Children’s self-esteem and social competence have been shown to be influenced by both parental and the child’s own acculturation styles.15

Stages of resettlement

Resettlement is considered to be a type of adaptation that can be divided into three or more personal stages, based on the literature on adaptation.16 Citizenship and Immigration Canada describes a commonly used four-step evolution. Knowing these stages can help health professionals to ‘locate’ newcomers in the adaptation process and, as a result, to better help with transitions from one stage to the next.

The newcomer experience often follows this trajectory:

Stage 1: Happiness and fascination

- occurs just before or shortly after arriving in Canada

- the person feels excited, confident, optimistic and has high hopes, and

- focuses on similarities between Canada and country of origin

Stage 2: Disappointment, confusion, frustration and irritation

- occurs during the first 6 months in Canada

- the person feels frustrated and disappointed, and

- focuses on differences between self and Canadians

- misses family, and feels lonely and guilty for leaving family members

Whenever possible, encourage newcomers to integrate by maintaining their culture of origin while actively participating in Canadian society.

Stage 3: Gradual adjustment or recovery

- the person feels more in control and confident

- starts to get involved in community

- better understands how to adapt to Canada

Stage 4: Acceptance and adjustment

- the person feels comfortable in Canada

- has made friends and is more involved in community

- understands how things are done in Canada

Adapting to challenges in Canada

Newcomers must continually adapt to many factors to which native-born Canadians may be oblivious. Often these factors are also social determinants of health.

- Language: Children usually learn new languages more quickly than parents. This proficiency can lead to children acting as interpreters for their parents or as cultural liaisons, roles which disrupt normal parent–child dynamics. Avoid using children as interpreters. Communicating through any ‘third party’ can be awkward. In a health care setting, especially when interpretation is done by children, both patient and provider may conceal some of the issues that really should be talked about. Also, a child may feel unsuited to this role. Read more about appropriate use of interpreters. Research has shown that physician–patient language concordance is associated with better health outcomes as it minimizes communication errors and increase rapport between clinicians and patients. In light of the ever-growing cultural diversity of the Canadian population, training, recruitment and retention of minority and language concordant medical staff may help provide culturally sensitive care.16

- Employment: Finding a job to match a newcomer’s skills or abilities can be challenging. Newcomers may be overqualified for the work they find because of language barriers or non-recognition of professional credentials. For example, someone who was an engineer in the home country may enter the Canadian workforce as a security guard. Newcomers often have to requalify or return to school to find suitable work in Canada. Adjusting to and accepting a loss in social status can be challenging for parents and for youth, even when they felt prepared for change. Skilled immigrants in Canada face substantially higher levels of unemployment and lower wages than non-immigrants.17 While this may partially be due to employers valuing Canadian education or work experience more than foreign education or experience, discrimination against immigrant applicants may also be at play. Research has shown that changing only the name on a resume from an English-sounding name to an Indian, Pakistani, or Chinese name decreased the likelihood of a callback from an employer by 4.4 percentage points from a base of 15.7 percent (a 28 percent decrease) when controlling for English language fluency as well as Canadian-based education and experience. Strategies to reduce hiring bias, such as masking names on applications, may help reduce call-back bias.17

- Income disparity: Recent immigrants are more likely to be among the working poor than native-born Canadians.18,19,20 Newcomers have difficulty equalling the economic means of native-born Canadians, and economic disparities are very much a part of life. Children may lose respect for their parents and feel like they don’t fit in with peers because their family can’t afford cable television, Internet access or cell phones. They may not be able to dress or participate in activities like other children. As noted, systemic discrimination against immigrants in the workforce prevents them from attaining meaningful and well-renumerated employment opportunities, therefore creating economic hardship and inequitable access to resources for their children.

- Gender roles: Couples may have to adjust to a new division of labour in the household, especially in terms of earned income and housework. Children may resent their mother working outside of the home. Some children may have to prepare meals or take care of siblings because both parents need to work.

- Climate: Newcomers from more temperate climates may not know how to dress for Canada’s weather, where to get proper clothes, or be able to afford winter wear. Dressing children for school in clothing appropriate to the season may need to be taught and, in some cases, subsidized.

- School: It’s crucial to assess how quickly children are adjusting to new school routines, social customs and language. Quick adaptation is more likely to result in healthy self-confidence, social competence and positive school performance. A child who did well in school previously may perform poorly in Canada because of language difficulties, racism or other factors. Identifying a child’s specific adaptation challenges is important. Families may not seek help if educational support and services are different from their country of origin. Children with special needs face the added difficulty of being assessed in a new language and culture. It is helpful to ask both a parent and the child specifically how they are adapting to the school system, and to identify their most challenging issues. Offer contact information for school and community services that can support adaptation and school success. There may also be issues when the standard of education of a person's home country is superior to Canada. Getting a child placed in the proper grade can be difficult since Canadian systems place children according to a student's age.

- Social norms: Parents and children may find adjusting to Canadian cultural norms and values a challenge, including lifestyles, beliefs, religion, privacy, work ethic, attitudes about smoking or drinking, social interactions and the pace of urban life, which can be much faster or slower than what they are accustomed to.

- Sense of security: Newcomers who have spent time in unsafe locations, such as a refugee camp or country with a history of violence, may over- or underprotect their children. Their gauge of danger may not be ‘in tune’ with their current environment. By contrast, other newcomers end up in unsafe neighbourhoods and may not know how to protect themselves from potential dangers.

- Child protection: The idea of child protection is foreign to some newcomers, who may use corporal punishment (spanking, hitting) to discipline children. Families may not understand the idea of “duty to report” that exists in Canada, and reporting can erode trust in the healtcare system. The Canadian Paediatric Society has information for parents on positive discipline.

- Housing: Low-income newcomers are more likely to live in overcrowded homes, substandard conditions and neighbourhoods with high rates of poverty or crime.18 Poor quality housing may include a difficult or unfair landlord and an unsecure neighbourhood where children are exposed to gangs, drugs or violence. Children may feel ashamed of where they live, socially ostracized, or uncomfortable about inviting other children to their homes. Some families may be experiencing electricity, household appliances and utility bills for the first time.

- System-level inequities: Discrimination and racist behaviour frequently target a foreign accent, difficulties learning English or French, a physical feature, immigrant identity or a parent’s literacy level. Forces of structural oppression, including environmental injustice, discriminatory employment policies, police violence, xenophobia, poverty, and racism, have a direct and sustained impact on wellbeing of newcomer children.21 As part of caring for newcomer children, it is our responsibility as physicians to advocate for their health and social equity at an institutional and health policy level. By assessing for potential impacts of social determinants of health on a child’s and their family’s wellbeing at each clinical visit, you will be able to better support the child to thrive.

Comprehending health, disease and treatment

How newcomers understand health issues can affect their ability to adapt and acculturate to Canada. Consider these scenarios:

- A patient believes that treatment is futile because illness is predetermined by fate.

- A patient rejects a mental health diagnosis because it is stigmatized in the old country.

- An injection is the only treatment for disease that a family will accept, even when other options are presented.

- You recommend behaviour change to help address a health issue, but are told the family believes there is no point in changing behaviours. They request that you provide medicine or refer them to someone who will do so.

Such scenarios are challenging for health professionals. You may need to meet with a family several times and try different communication styles before progress is made or trust levels are high enough for effective messaging. Read more about cultural context and newcomer family perspectives on health.

Some examples of specific cultural beliefs are given below. Remember that perceptions of health and disease can vary widely within cultures, so be careful not to overgeneralize:

- Folk medicine has a strong role in many Latino cultures.22

- Southeast Asians may believe that certain body parts are sacred, or that doctors and medicine can cure anything immediately.

- Some Vietnamese people believe that patients themselves are responsible for their health and health care. As a result, they may avoid seeking care.23

- Some people are fatalistic, believing that a disease or illness is their destiny or ‘fate’.24

- In some cultures it is not appropriate to make eye contact with a person in authority, such as a health practitioner, or to ask them questions.

- Some patients are unaware of the importance of filling prescriptions promptly or taking medications in the manner prescribed.25

These different understandings can affect the health of patients in terms of whether they accept a diagnosis, how they behave, and to what extent they comply with treatment suggestions.

Encourage newcomer families to ask questions about the health system: how it can help them, and how to navigate it. Some patients may feel dissatisfied if you don’t prescribe medication, or they may seek alternative, unproven treatments that can have a potentially negative impact on their health. More information can be found in the references and resources sections on this page.

Read more about strategies to deliver culturally competent care, how culture influences health and effective use of interpreters, elsewhere on this site.

Resilience

Resilience helps newcomers to cope and do well in Canada despite the difficulties they face while immigrating. Resilience can be a personality trait can be fostered by the migration experience, or can be a learned trait necessary to endure hardships and navigate challenging circumstances. Imagine the personal resilience that a child needs to become the head of a family at 14 years of age; or to sacrifice an education because rebels have set fire to the only school..

Three types of factors promote resilience in children (see Table 1):

- Those possessed by the child, including abilities and skills.

- Those in the child’s environment: the community network.

- The interaction between personal and contextual factors: e.g., meaning, values and faith.

Protective factors can work together to help newcomer children and youth establish and maintain a positive self-image, mitigate risk factors, and interrupt negative chain reactions. The resilient individual is more open to new experiences and opportunities, which in turn reinforce resilience. “Cultural connectedness” has been shown to be an important protective factor for youth.26

The health care provider’s role in identifying and maximizing such protective factors can help foster resilience in newcomer children and families and assist the adaptation process.27

Selected resources

- British Columbia Newcomers’ Guide to Resources and Services, available in multiple languages

- Canadian Immigrant. The three stages of resettlement.

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Welcome to Canada, what you should know.

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Language, Official Languages and Immigration: Obstacles and Opportunities for Immigrants and Communities.

- Canadian Council for Refugees, 1998. Best settlement practices: Settlement services for refugees and immigrants in Canada.

- Gunnestad A. Resilience in a cross-cultural perspective: How resilience is generated in different cultures. Journal of International Communication 2006;11.

References

- Gushalak BD, Pottie K, Hatcher Roberts J, et al. Migration and health in Canada: Health in the global village. CMAJ 2011;183(12):E952-8.

- McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Insights into the ‘healthy immigrant effect’: Health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Soc Sci Med 2004;59(8): 1613-27.

- Newbold KB, Danforth J. Health status and Canada’s immigrant population. Soc Sci Med 2003;57(10):1981-95.

- Dunn JR, Dyck I. Social determinants of health in Canada’s immigrant population: Results fro the National Population Health Survey. Soc Sci Med 2000;51(11):1573-93.

- Ng E, Wilkins R, Gendron F, et al. 2005.Dynamics of immigrants’ health in Canada: Evidence from the National Population Health Survey. In: Healthy today, healthy tomorrow? Findings from the National Population Health Survey. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, cat. no. 82-618-MWE2005002.

- Spitzer DL, ed. Engendering Migrant Health: Canadian Perspectives. Toronto, Ont.: University of Toronto Press, 2011.

- Vissandjee B, Desmeules M, Zheynuan C, et al. Integrating ethnicity and migration as determinants of Canadian women’s health. BMC Women’s Health 2004;4 (Suppl 1):S32.

- Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2011;183(12):E824-925.

- Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, et al. Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. App Psychol Int Rev 2006;55(3):303-32.

- Lysgaard, S. (1955). Adjustment in a foreign society: Norwegian Fulbright grantees visiting the United States. International Social Science Bulletin, 7, 45–51. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000033837

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology 1997;46(1):5-34.

- Pawliuk N, Grizenko N, Chan-Yip A, et al. Acculturation style and psychological functioning in children of immigrants. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1996;66(1):111-21.

- Berry JW. Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In: Chun K, Balls-Organista P, Marin G, eds. Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement and Applied Research. Washington, DC: APA Press, 2003:17-37.

- Vo DX, et al. Voices of Asian American youth: Important characteristics of clinicians and clinical sites. Pediatrics 2007;120(6):e1481-93.

- Chan-Yip A. Health promotion and research in the Chinese community in Montreal: A model of culturally appropriate health care. Paediatr Child Health 2004;9(9):627-29.

- Cano-Ibáñez N, Zolfaghari Y, Amezcua-Prieto C, Khan KS. Physician-Patient Language Discordance and Poor Health Outcomes: A Systematic Scoping Review. Front Public Health. 2021 Mar 19;9:629041. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.629041. PMID: 33816420; PMCID: PMC8017287.

- Oreopoulos, Philip. 2011. "Why Do Skilled Immigrants Struggle in the Labor Market? A Field Experiment with Thirteen Thousand Resumes." American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 3(4): 148-71.

- Winkelman M. Cultural shock and adaptation. J Counseling Development 1994; 73(2):121-36.

- Fleury D, Human Resources and Social Development Canada. A study of poverty and working poverty among recent immigrants to Canada: Final report, 2007.

- Kazemipur A, Halli S. The invisible barrier: Neighbourhood poverty and integration of immigrants in Canada. J Int Migr Integr 2000;1(1):85-100.

- William Okoniewski, Mangai Sundaram, Diego Chaves-Gnecco, Katie McAnany, John D. Cowden, Maya Ragavan; Culturally Sensitive Interventions in Pediatric Primary Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics February 2022; 149 (2): e2021052162. 10.1542/peds.2021-052162.

- DeBellonia RR, Marcus S, Shih R, et al. Curanderismo: Consequences of folk medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care 2008;24(4):228-9.

- Donnelly TT, McKellin W. Keeping healthy! Whose responsibility is it anyway? Vietnamese Canadian women and their healthcare providers’ perspectives. Nurs Inq 2007;14(1):2-12.

- Juckett G. Cross-cultural medicine. Am Fam Physician 2005;72(11):2267-74.

- Kang DS, Kahler LR, Tesar CM. Cultural aspects of caring for refugees. Am Fam Physician 1998;57(6):1245-56,1249-50,1253-4.

- Vo DX, Park MJ. Racial/ethnic disparities and culturally competent health care among youth and young men. Am J Mens Health 2008;2(2):192-205.

- Gunnestad A. (2006). Resilience in a cross-cultural perspective: How resilience is generated in different cultures. Journal of Intercultural Communication 2006;11.

Other resources consulted

- Ahonen EQ, Benavides FG, Benach J. Immigrant populations, work and health—a systematic literature review. Scand J Work Environ Health 2007;33(2):96-104.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Community Health Services. Providing care for immigrant, homeless, and migrant children. Paediatrics 2005;115(4):1095-1100.

- Beiser M. Strangers at the Gate: The ‘boat people’s’ first ten years in Canada. Toronto, Ont.: University of Toronto Press, 1999.

- Caulford P, Vali Y. Providing health care to medically uninsured immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2006;174(9):1253-4.

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Culture Shock and Cultural Adaptation.

- Curtis S, Setia MS, Quesnel-Vallee A. Socio-geographic mobility and health status: A longitudinal analysis using the National Population Health Survey of Canada. Soc Sci Med 2009;69(12):1845-53.

- Farmer P. Pathologies of Power: Health, human rights and the new war on the poor. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003.

- Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: A systematic review. Lancet 2005;365(9467):1309-14.

- Groleau D, Kirmayer LJ. Sociosomatic theory in Vietnamese immigrants’ narratives of distress. Anthropology and Medicine 2004;11(2):117-33.

- Gushulak BD, MacPherson DW. Migration Medicine and Health: Principles and practice. Hamilton, Ont.: B.C. Decker, 2006.

- Helman CG. Culture, Health and Illness, 5th edn. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group), 2007.

- Hyman I. Immigration and health: Reviewing evidence of the healthy immigrant effect in Canada. CERIS working paper 55. Toronto (Ont.): Joint Centre of Excellence for Research on Immigration and Settlement, 2007.

- Keane VP, Gushulak BD. The medical assessment of migrants: Current limitations and future potential. Int Migr 2001;39(2):29-42.

- Kirmayer LJ. Cultural variations in the clinical presentation of depression and anxiety: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62 Suppl 13:22-8, 29-30.

- Lai D, Chappell N. Use of traditional Chinese medicine by older Chinese immigrants in Canada. Fam Pract 2007;24(1):56-64.

- Kleinman A. Writing at the Margin: Discourse between anthropology and medicine. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997.

- Lin KM, Smith MW, Ortiz V. Culture and psychopharmacology. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2001;24(3):523-38.

- Médecins Sans Frontires. Refugee health: An Approach to emergency situations. Médecins Sans Frontières.

- Newbold KB. Health care use and the Canadian immigrant population. Int J Health Serv 2009;39(3):545-65.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. What Determines Health?

- Rasmussen A, Smith H, Keller AS. Factor structure of PTSD symptoms among West and Central African refugees. J Trauma Stress 2007;20(3):271-80.

- Reitz JG. Closing the gaps between skilled immigration and Canadian labour markets: Emerging policy issues and priorities. Toronto, Ont.: University of Toronto, 2007.

- Simich L, Wu F, Nerad S. Status and health security: An exploratory study of irregular immigrants in Toronto. Can J Public Health 2007;98(5)369-73.

- Vo DX, et al. Voices of Asian American youth: Important characteristics of clinicians and clinical sites. Pediatrics 2007;120(6):e1481-93.

- Walker PF, Barnett ED, Stauffer WM, eds. Immigrant Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier, 2007.

- Wang L, Rosenberg M, Lo L. Ethnicity and utilization of family physicians: A case study of Mainland Chinese immigrants in Toronto, Canada. Soc Sci Med 2008;67(9):1410-22.

Reviewer(s)

Ryan Giroux, MD

Sana Gill, MD

Last updated: February, 2025